Bill Bryson — Profile of a Travel Writer

Bill Bryson quit writing? I didn’t even hear it from him — Goodreads whispered the news. No farewell tour, no apology, just silence. My first literary crush hung up his pen as if we weren’t paying attention. Bryson was the rare writer who could pin your shirt to the wall with a sentence, make you laugh until your ribs ached, then slip a philosophical truth under your skin before you noticed.

“Take a moment from time to time to remember that you are alive,” he once wrote. “By the most astounding stroke of luck, an infinitesimal portion of all the matter in the universe came together to create you…” That’s Bryson: part stand-up comic, part philosopher, part passenger in the seat next to yours with crumbs on his sweater.

Raised in Des Moines, Iowa, he grew up watching European films — enchanted by cobblestones, hedgerows, and English accents. He dropped out of college, roamed Europe with a childhood friend named Katz, and knew England was his destiny. A job at The Times followed, but just as things steadied, America called him back. Then, in typical Bryson fashion, he decided to drive it.

And he did — in two bursts, East then West — through 38 states. No itinerary, no plan, just road. His book The Lost Continent turned that wandering into literature. Bryson could describe a motel check-in or a Gettysburg souvenir stand and leave you doubled over, gasping like you’d been sucker-punched with joy. His writing was slapstick philosophy: motels, battles, traffic jams, all delivered with wit sharp enough to draw blood.

Inspired, I climbed into my own 1978 Toyota Corolla, desperate for freedom from my parents’ separation and a girlfriend who wanted to move in. At 21, I wanted nothing except escape. I drove all 48 lower states, chasing Bryson’s ghost.

Like him, my road trip was chaos. My friend Dave and I left broke, partied in New Orleans on the last of our cash, then bought $12 worth of window-washing gear from a man in an alley and lived off storefronts. By night we pulled into rest stops, drank cheap beer, and plotted the next tank of gas. We stuck out in a canary-yellow car, traveling 24,000 miles with no plan but forward. In Des Moines, I even looked up Bryson’s mother in the phone book. She gave me his number in Yorkshire, England. I never called. Maybe he’s still waiting for that collect call, thirty years later.

Bryson followed with Neither Here Nor There, retracing his old Europe routes with Katz. He wrung jokes from bed-sits the size of broom closets and tours gone sideways. From Hammerfest to Istanbul, he sliced cultures with humor and affection. Then came A Walk in the Woods, his failed but hysterical attempt at the Appalachian Trail. Bears, blisters, bumbling — Bryson turned defeat into classic travel writing.

His reach widened: Notes from a Small Island charted every pub, path, and quirk of Britain with a lover’s devotion. The Mother Tongue celebrated English with the same warmth he once gave cobblestones. Book after book, he made readers accomplices — laughing with him, occasionally at him, but always listening.

Travel, for Bryson, was wonder weaponized: “I can’t think of anything that excites a greater sense of childlike wonder than to be in a country where you are ignorant of almost everything.” That was his gift — ignorance worn proudly, made holy by humor.

Which is why I refuse to believe he’s done. Bill Bryson retiring is like Gary Larson quitting The Far Side mid-strip, or Seinfeld canceling his show while the set’s still lit. The man drove 38 states. Steinbeck managed 27. Kerouac only 17. William Least Heat-Moon beat him with 39. That leaves ten states untouched.

So here’s the deal, Bill: pull up your Thunderbolt Kid underwear, grab your mom’s car keys, and finish what you started. Your readers are still here, engines running.

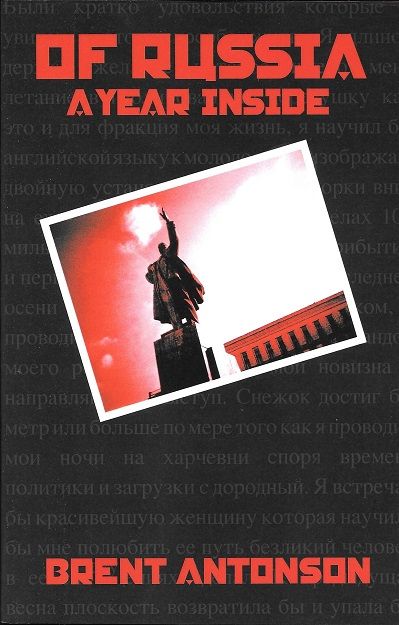

OF RUSSIA: A Year Inside

Brent (Brant is the Russian version) Antonson has seen a Russia few foreigners have. Indeed, few Russians. This young Canadian ventured to Voronezh, eleven hours south of Moscow by train, to spend a year inside a country torn by strife, fresh into a new century, and struggling with the clash between history and future. Tasked with teaching English to students at one university, and then a second, his story is riddled with romance and deception and punctuated with near disaster and disappointment. Antonson's candor and insights set Russia on the edge of failure and achievement – much like the students, he educated, filled with a dash of hope and a lump of fear. His wit did as much to get him in trouble as it did to keep him out of it.