Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote his 1860 semi-autobiographical The House of the Dead as a gritty memoir sharing the insufferable conditions of Russian imprisonment using the narrative of a man condemned for killing his wife. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote his 1962 short novel, A Day In The Life Of Ivan Denisovich, on the daily ritual of life in a concentration camp. Their books displayed Russia-as-prison in the 1850s and 1950s, and in both eras, there was plenty of misery to go around, an authoritarian world back on display today. I published my book on my time working in Russia in Of Russia: A Year Inside with my version of my short but torturous incarceration when teaching in Voronezh, Russia.

Au·thor·i·tar·i·an·ism = “the enforcement of strict obedience to authority at the expense of personal freedom.”

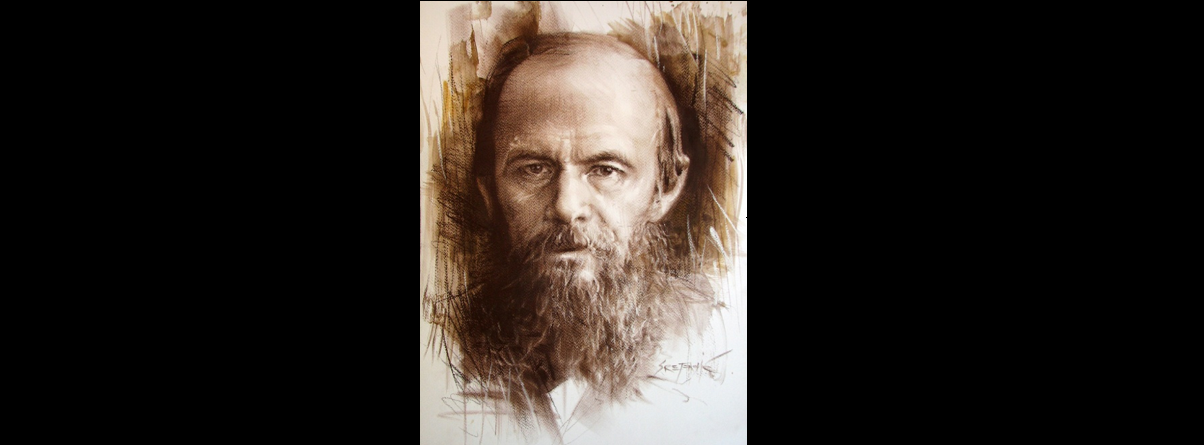

Dostoevsky had been raised with a nanny who read him bedtime stories. It was his favorite part of the day. Elena would read aloud heroic sagas, fairy tales and legends. His parents used the Bible to teach Fyodor how to read and write. During his later years in the military, the New Testament was all he was allowed to read.

Growing up, he was influenced by Russian authors such as Pushkin, Gogol, and Karamzin and a wide variety of Western philosophy from Plato to Shakespeare to Hegel. Given his fragile health and as an introvert, he did not like school but succeeded in making it through a military academy to work as a mechanical engineer. He frequently attended plays and the opera, and he was introduced to gambling by his brother, Mikhail. Gambling would become synonymous with Dostoevsky.

Dostoevsky joined a writer’s group that drew him into topics about freedom and questioned the czarist rule and developed his opinions on the political spectrum. Rulers deemed them to be "systematic opponents of all revolutionary goals and means." When that group disbanded, he joined the Petrashevsky Circle, thinkers who had harsh political views about freedoms, censorship, and the abolition of serfdom. Dostoevsky was charged with reading and circulating material against the state and sentenced to be executed.

Guards took Fyodor from his prison cell and led him into the early morning sun. Outside, heavy with shackled hands and feet, he was forced to walk by three of his blindfolded co-conspirators tied to poles. Fyodor was tied to the last pole, and his eyes were covered. The firing squad shouldered their rifles. “Five, four…" and shot his friends dead.

When it was his turn, the firing squad raised their guns and fixed their aim against Fyodor's heart. Not a moment too soon, a commander spoke, and soldiers lowered their guns. Fyodor was read a declaration that his sentence had been commuted. He would spend four years in a hard labor camp and a subsequent six years in the brutal military barracks. Ten years a convict.

Dostoevsky wrote about this imprisonment. "In summer, intolerable closeness; in winter, unendurable cold. All the floors were rotten. Filth on the floors an inch thick; one could slip and fall... We were packed like herrings in a barrel... There was no room to turn around. From dusk to dawn, it was impossible not to behave like pigs... Fleas, lice, and black beetles by the bushel."

After his incarceration, Dostoevsky wrote twelve novels. Most people are aware of Crime and Punishment, even if the title is all they have read. It is about a young man named Raskolnikov who kills a pawnbroker. He reasons that he has every right to do so, as she is a menace to him and does not bargain fairly. He murders her but then realizes the Raskolnikov he was before the murder is not the same Raskolnikov after the murder. The grim nine hundred pages consume the reader with the deepest and darkest of the human psyche. The psychological spectrums on murder and its mental consequences are palatably explored to their cryptic lengths. Dostoevsky's experiment in philosophical writing leapt off the page. He held terror up to the light and examined the daylights out of it. Nietzsche called Dostoevsky “the only person who has ever taught me anything about psychology.”

Amid writing his long novels, Dostoevsky produced 16 short stories that kept him financially afloat. He was tender yet afflicted, romantic yet forlorn. His grasp on the human life— social, political, or sexual—is organic and intrusive. Russian prison had shaped his writing. Dostoevsky’s greatest thoughts were summed up alternately in a quotable line or a thousand pages.

To go wrong in one's own way is better than to go right in someone else's.”

― Fyodor Dostoevsky

Ernest Hemingway said in Dostoevsky," "there were things believable and not to be believed, but some so true that they changed you as you read them; frailty and madness, wickedness and saintliness, and the insanity of gambling were there to know". Franz Kafka called Dostoevsky his "blood-relative" in a way to bond their gloomy and nightmarish writing principles. And fellow Russian author Maxim Gorky described Dostoevsky retrospectively as “our evil genius.”

Dostoevsky authored soul-shuddering novels or short psychotherapeutic stories with worldly philosophic episodes puncturing his stories. He dashed scenes with a gritty satire and measurable stoicism poised against his personal prevalent conditions, notably debt. Gambling took all his resources and left him at one point begging in the street. While he never was in excess or living large, he remains a rather prided, yet sad, example of the proletariat. He died in 1881.

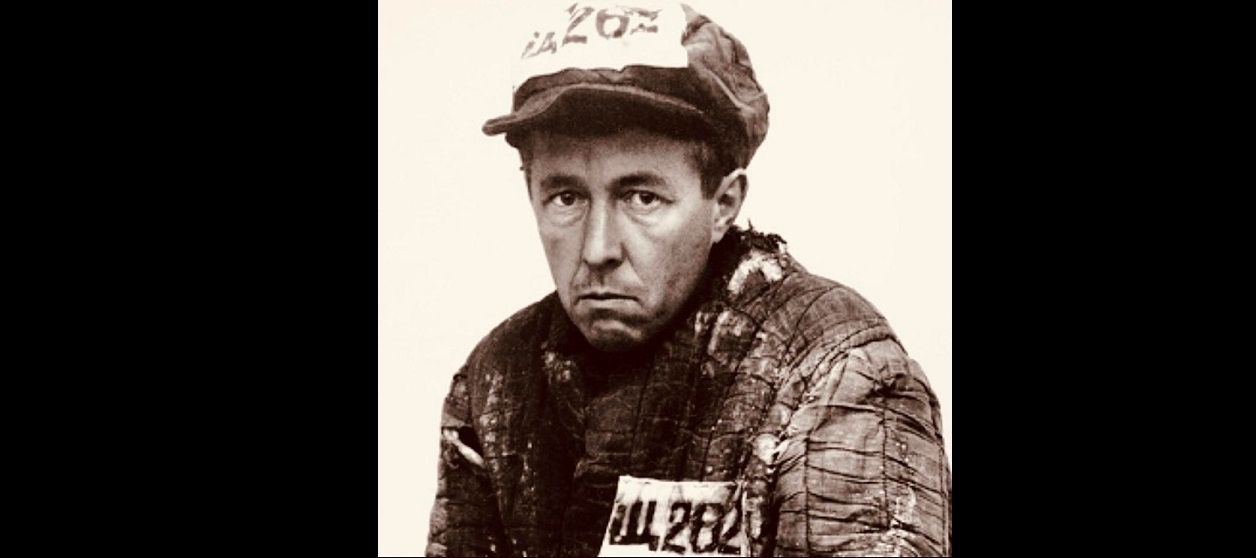

Solzhenitsyn was a young atheist, an ardent Marxist-Leninist, and a loyal patriot serving in the Red Army during the Second World War. He was arrested for discerning remarks against Stalin in a private letter to a friend and imprisoned for eight years in a Russian gulag. Solzhenitsyn was released and exonerated when Stalin died as a result of the "Khrushchev Thaw."

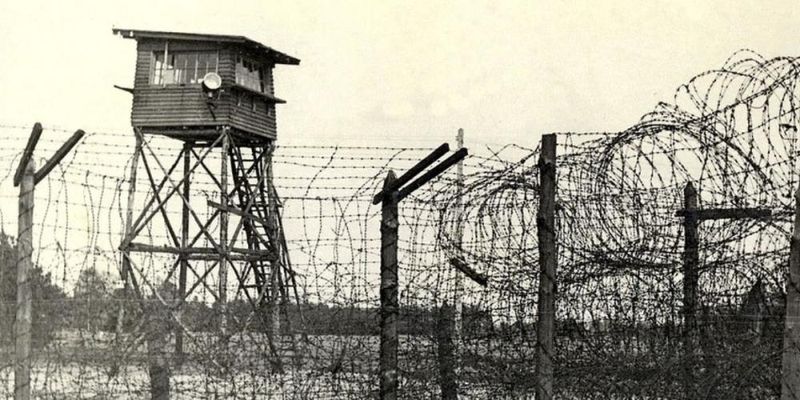

Solzhenitsyn's A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich begins with a workday in a gulag in the cold conditions Siberia can manifest. The men hover around a thermometer, hoping it read colder than -40C, a temperature at which they did not have to work, urging each other not to breathe the slightest of warm air near the thermometer. Alas, the thermometer was stuck at -39C, so the men went off to build a wall for more barracks. More prisoners came to fill the overcrowded barracks that stank. The workdays involved a sledgehammer, trowel, or shovel working in forestry, mining, and farming, to factory work. This book was released with Khrushchev's approval as it showed the terrible life under Stalinism.

A decade later, Solzhenitsyn made himself a target when he released The Gulag Archipelago, a non-fictional collection of notes, conversations, legal documents, reports, interviews, statements, diaries, and his own time in the Gulag system.

Elaborate attempts to publish The Gulag Archipelago involved the KGB, spies, and microfilms. The thunderous three volumes were hoped to be published within the USSR, but the times were not such that it could be done. Since he was always under KGB surveillance, the manuscript was worked on it in parts hidden at the houses of acquaintances where he could visit and go largely undetected. A woman who typed his manuscript for him was interrogated by the KGB and told them where a printed copy was to be found. Her body was found hanging in a suicide or murder, three days after her release. However, multiple copies were sent to Paris secretly in both print and microfilm formats and released to the world in 1973.

You only have power over people as long as you don't take everything away from them. But when you've robbed a man of everything, he's no longer in your power—he's free again.”

― Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

During the Cold War, the world heard little from the other side of the Iron Curtain with regard to the huge swathe of prisoners in the gulag system. "Archipelago" awoke the West and drew criticism for the Soviet gulag system of incarceration. It has been required reading in Russian schools since 2009, though one wonders if that requirement will be abandoned in 2022 with the rise of Russian authoritarianism.

Solzhenitsyn was awarded the 1970 Nobel Prize in Literature "for the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature". But he found himself in exile, living out much of the rest of his life in America. He spent the last four years of his life in a new Russia and died there in 2008.

Under the penname Brant Antonson, I wrote Of Russia; A Year Inside, including a Russian prison encounter of my own in 2001, not unlike millions of other Russians have faced. I hitch my tale to the tattered literary coattails of Dostoevsky’s and Solzhenitsyn’s stories to illustrate what so many Russians still encounter today–should they run afoul of authoritarianism.

At the time, I taught English at the Institute of Law and Economics in Voronezh as well as the State University of the Russian Federation. One day I was cleaning my flat and found six rolls of undeveloped pictures. I had not heeded warnings about what was permissible to photograph. And developing more than one roll of film at a time was reason for people to be curious. Those mistakes compounded.

Russians, in the days of cameras with film, did not develop full rolls. They were given the negatives and would go to a lightboard and choose which ones to pay to have developed. Often only five negatives of 24 exposures were developed.

I dropped off six rolls of film at the Konica shop paying to have every negative printed, returning with heavy bags of prints. There was a bench and a lopsided table in the dirt yard behind my apartment building. Babushkas and dedushkas sat about. I decided to show them—mindfully unaware of what was inappropriate—my pictures of Moscow and Saint Petersburg.

My innocence was my naiveté—which suddenly did not pass for innocence. The film processing shop had reported me. Two police officers quickly came around the corner, arrested me, and collected the photographs. The officers then force-marched me across the street to a small jail cell tucked amid a hundred kiosks. While I sat there where they pushed me, roving groups of police drove up (always four to a car) and went through my photos. They laughed, roared, and pointed at me. My Russian language was not strong enough to solve my situation. Six hours later it grew dark, and I fell asleep.

In a darkness, the police roused me and put me alone into the rear of a paddy wagon without windows. We drove four or five kilometers to a precinct whereupon the prison doors flung open. As I prepared to greet whoever was there, a police officer grabbed the collar of my trench coat and threw me down a dozen concrete stairs. I was knocked unconscious.

I awoke in another darkness, covered with blood, and being beaten mercilessly. I’d been stripped. I was clad only in my underwear. I did not know how long I'd been unconscious. A bunch of men lifted me up against the wall by my ribcage, then dropped me. Again. And again. My legs lost all sensation. They kept slamming their hands over my ears, resulting in two perforated eardrums and severe tinnitus. They choked me, spit on me, and dragged me around by my numb legs. They broke my ribs and deformed my sternum. I was temporarily paralyzed from the waist down.

They dragged me out in front of an ugly man who looked more important, had more chevrons on his shoulder. There was no seat. I had to hold onto the edge of a desk. One by one, we went through the 144 photos and negatives. With my meagre Russian language, I realized how much trouble I could be in. I had jeopardized my jobs and living situation by taking pictures of things one is not supposed to photograph in Russia. Among benign shots of classrooms and students, I had taken pictures of the airport, military installations, tanks, the open market, beggars, even passing police officers at the train station, and naked girlfriends. I hadn't really felt like the Iron Curtain rules existed to me.

Once we had gone through the pictures, I was thrown back into a cell that echoed the lone word of a police officer, "shpion" or "spy". I was beaten on and off until sunrise when I was hauled to where my clothes were. $80 USD and many pictures were missing.

I painfully pulled myself, as my legs were too weak to walk, up the same twelve prison stairs I had been thrown down the night before. I scrambled to the public sphere as fast as my elbows could drag me. I locked my knees together as best I could and dragged my now clothed self away from the precinct. My head was screaming with a high-pitched static, I had a concussion. Broke and broken, I hitchhiked to my flat, where a girlfriend was waiting for me under the premise that something terrible must have happened to me. It had.

When the head of security for the Institute where I taught went to the police station to find out what had happened to me while I was incarcerated, there were no details, no notes, no intake report, nothing saying I had ever been in the Russian prison system. And there I was, partially paralyzed, trying to pack a years’ worth of my belongings into my luggage ready to catch the first flight out of Russia once I’d obtained an Exit Visa. It was overly complicated and I needed my colleagues to take me to hospitals and obtain the necessary documents.

If there are two authors I revere regarding the Russian/Soviet system of imprisonment, they are Dostoevsky in The House of the Dead, and Solzhenitsyn in The Gulag Archipelago. They made the reading world aware of the injustices in each epoch. It is unlikely we ever would have known the Russian imprisonment atrocities that occurred in the gulags without their narratives. Through them, we mark the history and ongoing dangers of the Soviet authoritarian regime—today writ large by Russia’s behavior in Ukraine.

OF RUSSIA: A Year Inside

Brent (Brant is the Russian version) Antonson has seen a Russia few foreigners have. Indeed, few Russians. This young Canadian ventured to Voronezh, eleven hours south of Moscow by train, to spend a year inside a country torn by strife, fresh into a new century, and struggling with the clash between history and future. Tasked with teaching English to students at one university, and then a second, his story is riddled with romance and deception, and punctuated with near disaster and disappointment. Antonson's candor and insights set Russia on the edge of failure and achievement – much like the students he educated, filled with a dash of hope and a lump of fear. His wit did as much to get him in trouble as it did to keep him out of it.