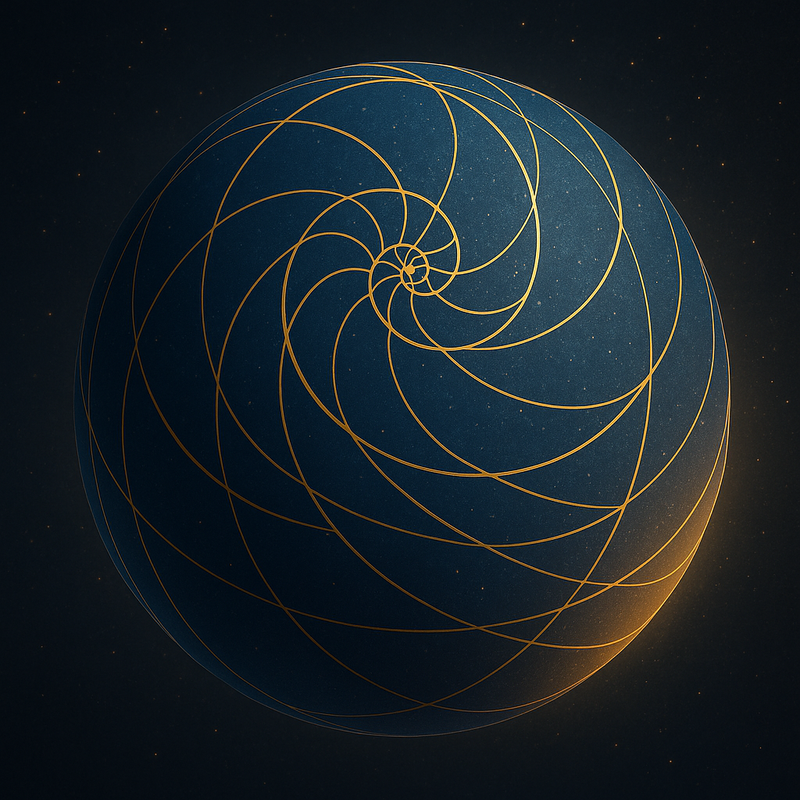

The Sphere, the Circle, and the Dance of Phi

A circle is simple. A curve that closes upon itself, flat yet infinite in symmetry. From any angle, a sphere is only a circle seen differently — but the moment it spins, it reveals depth. That spin invites a new player into the geometry: the golden ratio, φ.

π is closure. It tells us how much boundary is needed to enclose an area, how much surface to wrap a volume. In a circle, π measures circumference and area. In a sphere, π scales upward, giving surface area and volume. π is the mathematics of containment.

φ is distribution. It emerges not from boundaries but from arrangements within them. With circles, φ appears in pentagons, decagons, and the recursive spiral. With spheres, φ governs the most efficient way to distribute points across a surface. The Fibonacci sphere algorithm — the same spiral underlying sunflower seeds and pine cones — relies on φ intervals to balance density without overlap. Nature applies it instinctively: viruses crystallize into icosahedral shells, radiolaria spin their glass bones in φ symmetry, and even planets breathe their magnetic fields in spiral arcs.

When you rotate a circle, you sweep out a sphere. When you distribute across that sphere, you need φ. In other words:

- π creates the body, the closure of space.

- φ choreographs the dance, the growth across that body.

The congruence is elegant: π and φ are not rivals but complements. π closes, φ unfolds. Together, they explain why spheres dominate physics. Planets, bubbles, and cells emerge because the sphere is the most efficient enclosure (π). Their growth, distribution, and resonance emerge because φ is the most efficient arrangement.

Thus, the circle becomes the sphere by rotation, and the sphere becomes alive by φ.

π is the measure of stillness. φ is the measure of becoming.

The universe chose both.