The Unseen Anchor: Navigating the Problem of Induction in Scientific Discovery

Summary: The Shaky Ground Beneath Our Certainties

At the heart of scientific endeavor lies a fundamental philosophical challenge: the problem of induction. While science prides itself on empirical observation and logical deduction, a vast portion of its methodology—from forming general laws to predicting future events—rests on inductive reasoning. This article explores how our reliance on past experiences to infer future outcomes, though seemingly indispensable, lacks a purely logical justification, casting a subtle yet profound shadow over the very foundation of scientific knowledge and certainty. It's a problem that forces us to question the bedrock of our understanding, revealing a persistent chasm between observation and absolute logic.

The Invisible Engine of Progress: How We Generalize from Experience

From the moment we observe the sun rising day after day to the most complex experiments confirming a physical law, humanity operates under an implicit assumption: that patterns observed in the past will continue into the future. This process, moving from specific observations to general conclusions, is known as induction. It's the silent engine driving much of our learning, predicting, and, crucially, scientific discovery. Without it, every new observation would be an isolated event, disconnected from what came before, rendering systematic knowledge impossible.

Consider the simple act of turning on a light switch. You expect the light to illuminate because it always has in the past. This isn't a logical deduction; it's an inductive leap based on repeated experience. Science takes this everyday intuition and elevates it, building elaborate theories and predictive models upon countless such leaps. But what if the light doesn't turn on next time? Or, more profoundly, what if the laws of physics themselves subtly shift?

What is Induction? Bridging the Gap Between "Is" and "Will Be"

To fully grasp the problem, we must first understand induction itself. In its simplest form, it's a type of logic where we infer a general rule from specific instances.

- Example 1: Every swan I have ever seen is white. Therefore, all swans are white. (A classic, if flawed, example).

- Example 2: Water has boiled at 100°C under standard atmospheric pressure every time it has been tested. Therefore, water will always boil at 100°C under standard atmospheric pressure.

This contrasts sharply with deductive reasoning, which moves from general premises to specific, logically certain conclusions (e.g., "All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal"). Deductive arguments, if their premises are true, guarantee the truth of their conclusions. Inductive arguments, however, do not. They offer probabilities, not certainties.

The Inductive Leap: A Necessary Act of Faith?

The core of the problem lies in the "leap" we make. When we say, "Because X has happened in the past, X will happen in the future," we are not using a self-evident truth or a provable logical step. We are assuming a fundamental regularity of nature.

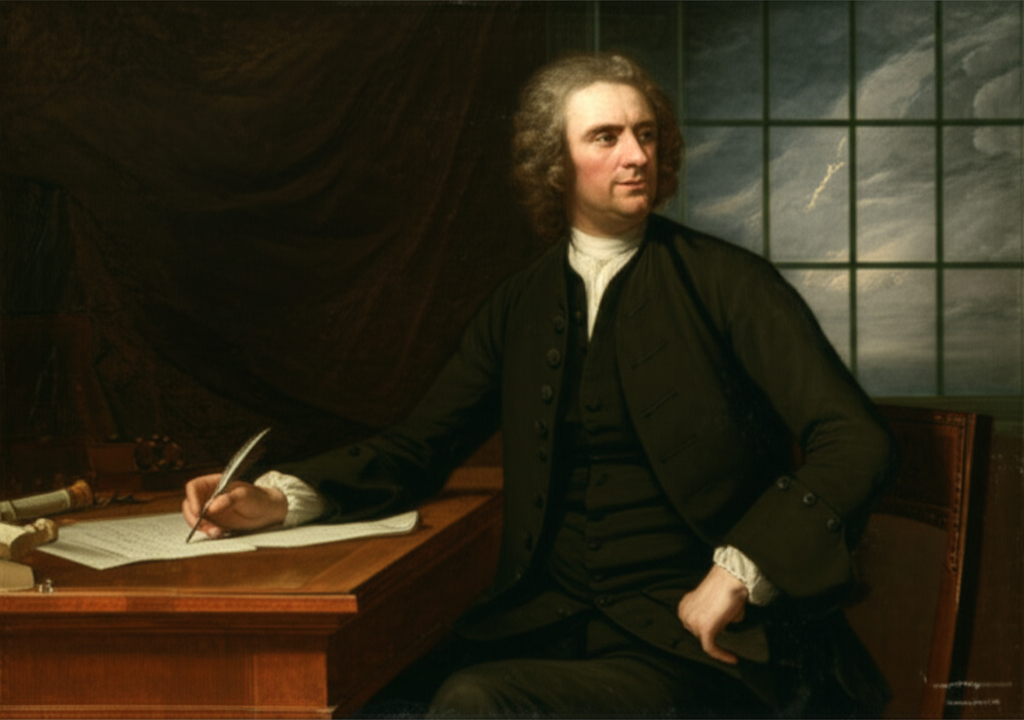

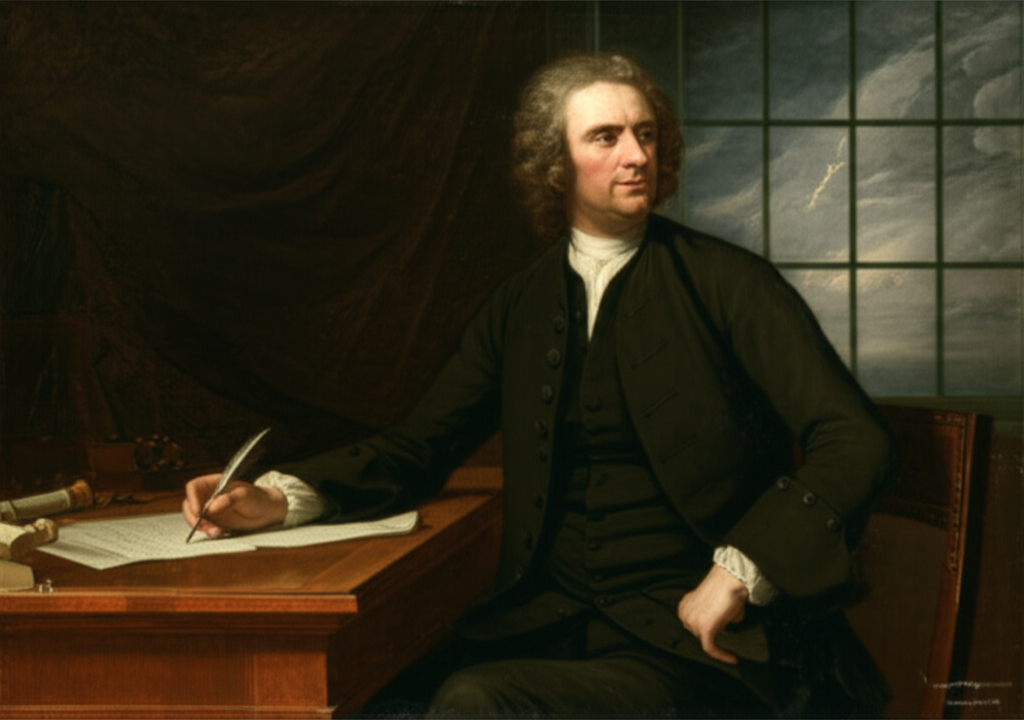

Hume's Skeptical Hammer: Unmasking the Flaw in Our Logic

The problem of induction was most famously articulated by the Scottish philosopher David Hume in the 18th century, a pivotal figure whose insights continue to reverberate through philosophy and science. Hume argued that there is no rational, logical justification for believing that the future will resemble the past.

Hume meticulously demonstrated that any attempt to justify induction inevitably falls into a trap of circular reasoning:

The Uniformity of Nature Assumption

To justify induction, we often appeal to the idea that nature is uniform, that its laws are constant across time and space. We believe this because, in the past, nature has appeared uniform. But this very belief is itself an inductive conclusion! We are using induction to justify induction, which is no justification at all in terms of pure logic.

The Circular Reasoning Trap

- Premise 1: The future has always resembled the past so far.

- Premise 2: Therefore, the future will resemble the past.

- Conclusion: Induction is a reliable method of reasoning.

Hume highlighted that this argument itself relies on the very principle it's trying to prove. It's like trying to prove the reliability of a witness by having that witness testify to their own reliability. This insight was profoundly unsettling, for it suggested that our most fundamental assumptions about the world lack a rational basis.

The Problem's Pervasive Reach in Scientific Practice

Hume's challenge isn't merely an abstract philosophical puzzle; it strikes at the very heart of how science operates and generates knowledge.

Where Science Relies on Induction:

| Scientific Activity | Inductive Leap |

|---|---|

| Formulating Laws | Observing countless instances of phenomena (e.g., falling objects) to derive universal laws (e.g., gravity). |

| Experimental Verification | Repeating experiments and assuming the results will be consistent in future trials. |

| Predictive Power | Using established theories (based on past observations) to forecast future events or discoveries. |

| Medical Trials | Assuming a drug's effectiveness in a trial group will generalize to the wider population. |

| Statistical Inference | Drawing conclusions about a large population based on a sample. |

Every scientific theory, no matter how robustly supported by evidence, ultimately rests on the inductive assumption that the patterns observed will persist. We have no logical guarantee that the laws of physics won't change tomorrow, or that gravity will continue to function as it always has.

Seeking Justification: Responses and Pragmatic Solutions

Philosophers and scientists have grappled with Hume's problem for centuries, proposing various solutions, though none have definitively resolved the logical impasse:

- Pragmatic Justification: Some argue that while induction cannot be logically proven, it is the best and only method we have for navigating the world and gaining knowledge. It works, even if we don't know why it works in a strictly logical sense.

- Falsification (Popper): Karl Popper famously proposed that science doesn't actually rely on induction for proof, but rather on deduction for falsification. Scientists propose bold conjectures and then attempt to deductively prove them false. A theory gains strength not by being "proven" true inductively, but by surviving repeated attempts at falsification. However, even the decision to continue using a theory that hasn't been falsified still has an inductive flavor.

- Bayesianism: This approach uses probability theory to update our beliefs as new evidence comes in. While it provides a rigorous framework for managing uncertainty, it doesn't escape the fundamental inductive assumption about the continuity of underlying probabilities.

The Enduring Philosophical Quagmire: A Humbling Truth for Knowledge

The problem of induction remains a profound challenge to our understanding of knowledge and logic. It reminds us that even our most rigorous scientific endeavors operate on a foundation that is, from a purely rational standpoint, unproven. Science provides us with incredibly effective tools for understanding and manipulating the world, but it cannot offer absolute logical certainty about the future.

This doesn't invalidate science or render its findings meaningless. Far from it. Instead, it offers a humbling insight into the limits of human reason and the indispensable role of empirical observation and pragmatic inference. We proceed with induction not because it is logically perfect, but because it is the only viable path to progress and survival. The sun will likely rise tomorrow, and gravity will likely continue to pull us downwards, not because logic dictates it, but because our experience overwhelmingly suggests it, and our very capacity for knowledge depends on that assumption.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "David Hume problem of induction explained"

-

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Karl Popper falsification vs induction"