The Nature of Justice in a Democratic State

Summary: The pursuit of Justice stands as the perennial quest of human civilization, finding its most intricate and challenging expression within the framework of a Democratic State. This exploration delves into the philosophical underpinnings and practical applications of Justice when entrusted to the collective will of the people and enshrined within a Constitution. We will navigate the historical evolution of these concepts, examine the mechanisms through which a Government endeavors to uphold fairness and equity, and confront the inherent tensions and contemporary challenges that define this vital intersection. Ultimately, understanding Justice in a Democracy is not merely an academic exercise, but a critical reflection on the very legitimacy and survival of our political order.

Introduction: The Enduring Quest for a Just Society

From the earliest city-states to the sprawling global community of today, humanity has grappled with the profound question of Justice. What does it mean for a society to be just? How should resources, rights, and responsibilities be distributed? And critically, how can these ideals be realized within a State where power theoretically resides with the people – a Democracy?

The relationship between Justice and Democracy is a dynamic and often fraught one. While Democracy promises equality and self-governance, Justice demands fairness, impartiality, and the protection of fundamental rights, even against the will of a majority. This intricate dance forms the bedrock of a stable and legitimate Government. This page embarks on a philosophical journey, drawing from the wisdom of the Great Books of the Western World, to unpack the multifaceted nature of Justice within the democratic experiment, exploring its historical roots, its contemporary manifestations, and the perpetual challenges to its realization.

I. Defining the Pillars: Justice, Democracy, and the State

To understand their interplay, we must first articulate the core concepts themselves. Each term carries a rich philosophical legacy, shaping our expectations of governance and societal organization.

- Justice: More than mere adherence to Law, Justice encompasses notions of fairness, equity, moral rightness, and the proper ordering of society. It is the principle that ensures individuals receive what is due to them, whether in terms of rights, opportunities, or retribution.

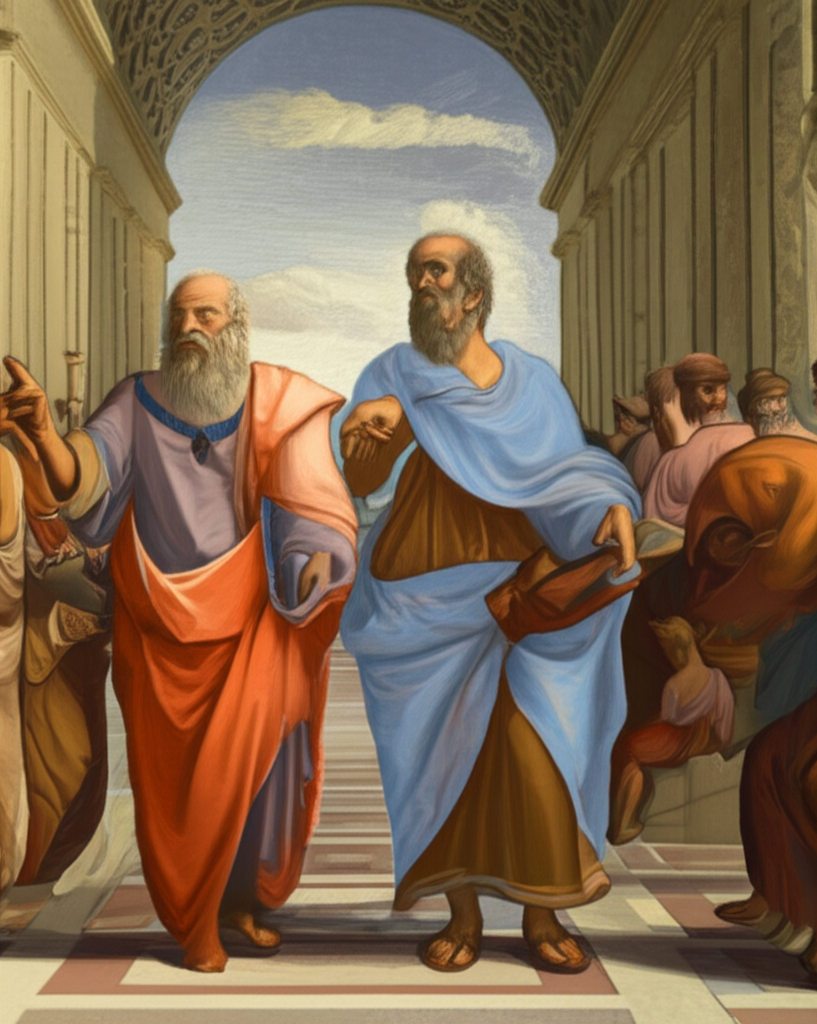

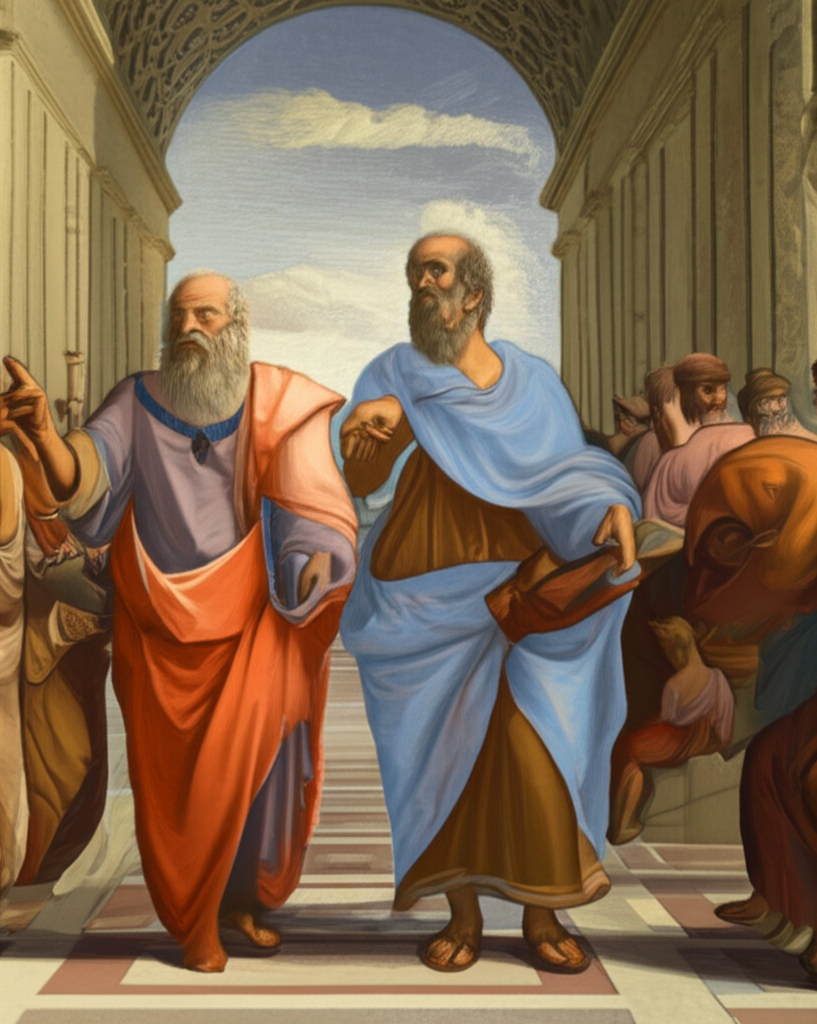

- For Plato, in The Republic, Justice in the State is akin to harmony within the soul: each part performing its proper function, leading to overall virtue and stability.

- Aristotle, in Nicomachean Ethics, distinguished between distributive Justice (fair allocation of goods and honors) and corrective Justice (rectifying wrongs through punishment or compensation).

- Democracy: Derived from the Greek demos (people) and kratos (power), Democracy signifies rule by the people. Its core tenets include popular sovereignty, political equality, individual liberties, and free and fair elections.

- Ancient Athenian Democracy was direct, while modern Democracy is typically representative, relying on elected officials to make decisions on behalf of the citizenry.

- The State: This refers to the political entity that holds sovereign power over a defined territory, possessing institutions for the making and enforcement of Law. It is the organizational structure through which Government operates.

- Philosophers like John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau explored the origins of the State through the concept of a "social contract," where individuals surrender certain freedoms in exchange for the protection of rights and the establishment of Justice through a common Law.

II. Historical Threads: From Ancient Polis to Modern Republic

The intellectual lineage of Justice in a political State is long and complex, evolving with each major philosophical paradigm shift.

A. Ancient Greek Foundations: Plato and Aristotle

The foundational discussions on Justice within a political community can be traced to ancient Greece.

- Plato's Ideal State: In The Republic, Plato grapples with the concept of Justice not as a set of laws, but as an inherent virtue of the State itself. He envisions an ideal State ruled by philosopher-kings, where each class (guardians, auxiliaries, producers) performs its function, leading to a harmonious and just society. For Plato, true Justice is absolute and discoverable through reason, often standing in tension with the fickle nature of democratic rule.

- Aristotle's Practical Justice: Aristotle, more empirically minded, viewed Justice as central to the purpose of the polis (city-state). In his Politics and Nicomachean Ethics, he argued that the best Constitution (polity) aims for the common good and ensures Justice through proportionate distribution and adherence to Law. He saw Democracy as one form of Government, potentially prone to mob rule, and sought a mixed Constitution that balanced elements of oligarchy and Democracy to achieve stability and Justice.

B. The Enlightenment and Social Contract Theories

The Enlightenment period profoundly reshaped our understanding of the State, Government, and individual rights, laying the groundwork for modern Democracy.

- John Locke: In his Two Treatises of Government, Locke argued that individuals possess natural rights (life, liberty, property) that pre-exist the State. Government is formed through a social contract to protect these rights, and its legitimacy derives from the consent of the governed. Justice, for Locke, is the State's adherence to this contract and its Law, ensuring the protection of individual freedoms.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Rousseau, in The Social Contract, posited that true Justice in a State comes from the "general will" of the people. Citizens, by obeying laws they themselves have collectively made, remain free. This concept places popular sovereignty at the heart of Justice and Law, though it also raises questions about minority rights within a democratic framework.

C. Modern Democratic Thought: John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill, in On Liberty, championed individual freedom and the limits of Government power. He argued that the State's interference with individual liberty is only justified to prevent harm to others (the "harm principle"). For Mill, a just Democracy protects a wide sphere of individual rights and freedoms, allowing for intellectual and moral progress, even if those views are unpopular. The Constitution and Law serve to safeguard these liberties.

III. The Mechanisms of Justice in a Democratic State

How does a Democracy translate philosophical ideals of Justice into tangible realities? It does so through a complex array of institutions, principles, and practices.

A. The Rule of Law and the Constitution

At the heart of any just Democracy is the Rule of Law. This principle dictates that all individuals, including those in Government, are subject to and accountable under the Law.

- Impartiality: Law must be applied equally to all, without favour or prejudice.

- Supremacy of the Constitution: The Constitution serves as the supreme Law of the land, establishing the framework for Government, defining its powers, and, crucially, guaranteeing fundamental rights and liberties. It acts as a bulwark against arbitrary power and ensures that the pursuit of Justice remains within defined bounds.

- Independent Judiciary: An impartial judiciary is essential for interpreting the Law and ensuring its just application, serving as a check on legislative and executive power.

B. Democratic Participation and Representation

The democratic process itself is a mechanism for shaping and enacting Justice.

- Elections: Allow citizens to choose representatives who will advocate for their vision of Justice.

- Freedom of Speech and Assembly: Enable public discourse, dissent, and the articulation of grievances, pushing the Government to address perceived injustices.

- Majority Rule, Minority Rights: A key challenge is balancing the will of the majority with the protection of the rights of minority groups, ensuring that democratic Justice does not devolve into tyranny of the majority.

C. Distributive Justice and Social Equity

Beyond legal equality, a just Democracy often strives for social and economic equity.

- John Rawls's "Justice as Fairness": In A Theory of Justice, Rawls proposed a thought experiment (the "veil of ignorance") to determine principles of Justice. His theory suggests that a just society would prioritize equal basic liberties for all and arrange social and economic inequalities to benefit the least advantaged (the "difference principle").

- The Welfare State: Many democratic States employ social programs, progressive taxation, and regulations to mitigate economic disparities and ensure a minimum standard of living, reflecting a commitment to distributive Justice.

D. Corrective Justice and Accountability

When Law is broken or rights are violated, a just Democracy must provide mechanisms for redress and accountability.

- Criminal Justice System: Designed to investigate crimes, apprehend offenders, and administer punishment, guided by principles of due process and fair trial.

- Restorative Justice: Approaches that focus on repairing harm caused by crime, involving victims, offenders, and the community in finding solutions.

- Government Accountability: Mechanisms like administrative Law, ombudsmen, and freedom of information acts ensure that the Government itself is held accountable for its actions and failures to uphold Justice.

IV. Challenges to Justice in Contemporary Democracies

The quest for Justice in a Democratic State is an ongoing struggle, beset by persistent and evolving challenges.

A. The Tension Between Liberty and Equality

One of the most enduring dilemmas is how to reconcile individual liberty with the pursuit of greater social and economic equality.

- How much State intervention is justifiable to achieve distributive Justice without infringing on personal freedoms or property rights?

- This tension is often reflected in debates over taxation, regulation, and social welfare programs.

B. Populism and the Erosion of Institutions

The rise of populist movements in many democracies poses a significant threat to established notions of Justice and the rule of Law.

- Populism can sometimes prioritize the direct, unmediated will of "the people" over constitutional checks and balances, the independence of the judiciary, or the rights of minorities.

- This can lead to challenges to the very institutions designed to ensure impartial Justice.

C. Globalisation and Transnational Justice

In an interconnected world, many injustices transcend national borders, challenging the capacity of individual democratic States to address them.

- Issues like climate change, human rights abuses, and economic exploitation require international cooperation and the development of transnational mechanisms of Justice.

- The limits of national Law and Government in a globalized context are increasingly apparent.

D. The Digital Age and Information Overload

The proliferation of information, and misinformation, in the digital age impacts democratic discourse and the pursuit of Justice.

- Echo chambers and filter bubbles can fragment public understanding of facts and ethical principles.

- The spread of disinformation can undermine trust in institutions and the very concept of objective Justice.

V. Cultivating a Just Democracy: A Path Forward

The pursuit of Justice in a Democratic State is not a destination but a continuous journey, demanding vigilance, participation, and a steadfast commitment to core principles.

- Civic Engagement: An active, informed citizenry is the bedrock of a just Democracy. Participation in political processes, advocacy, and community organizing are vital.

- Strengthening Constitutional Frameworks: Upholding the Constitution and supporting independent institutions (like the judiciary and a free press) are crucial for safeguarding Justice against popular impulses or authoritarian tendencies.

- Education and Critical Thinking: Fostering critical thinking skills and a deeper understanding of philosophical principles helps citizens navigate complex ethical dilemmas and discern true Justice from mere self-interest.

- Dialogue and Empathy: Encouraging open dialogue across divides and cultivating empathy for diverse perspectives are essential for building consensus and understanding the varied experiences of injustice within a pluralistic society.

Conclusion: The Perpetual Project of Justice

The nature of Justice in a Democratic State is a profound and intricate tapestry woven from philosophical ideals, historical struggles, and the ongoing efforts of citizens and their Government. It is a project that demands constant reflection, adaptation, and unwavering commitment. As we draw from the wisdom of the Great Books, we recognize that the questions posed by Plato, Aristotle, Locke, Rousseau, and Mill remain acutely relevant. A truly democratic State strives not merely for rule by the people, but for a rule that is fundamentally just, ensuring that the Law, the Constitution, and the actions of the Government serve the common good and protect the inherent dignity of every individual.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Justice: What's The Right Thing To Do? Michael Sandel""

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Republic: Justice and the Ideal State Explained""