The Enduring Dialogue: Art, Form, Beauty, and Quality

The essence of art has captivated thinkers for millennia, from the pre-Socratics to contemporary philosophers. At its heart lies a profound interplay between Art, Form, Beauty, and Quality. This article delves into the philosophical underpinnings of these concepts, drawing heavily from the rich tapestry of ideas presented in the Great Books of the Western World. We will explore how ancient insights into the structure of reality inform our understanding of artistic creation and appreciation, revealing that the nature of art is not merely an aesthetic pursuit, but a deep engagement with fundamental truths about existence itself.

The Philosophical Foundations of Form in Art

To understand art, one must first grapple with the concept of Form. For many classical thinkers, Form was not merely an external shape but the intrinsic essence, structure, or ideal pattern of a thing. This understanding profoundly influenced how art was conceived.

Plato's Ideal Forms and the Artist's Challenge

Plato, in works like The Republic, posited a realm of perfect, immutable Forms existing independently of the physical world. For him, the tangible objects we perceive are mere shadows or imperfect copies of these ideal Forms. Art, particularly mimetic art (imitation), was thus often viewed as a "copy of a copy," twice removed from ultimate reality.

- The Artist's Dilemma: While Plato was wary of art's potential to mislead, he also acknowledged its power. The challenge for the artist, then, was not merely to imitate the visible world, but perhaps, implicitly, to strive towards revealing something of the Form behind the appearance – to imbue their creation with a glimpse of ideal Beauty or truth. The sculptor, in shaping marble, aims not just for a likeness but for an embodiment of an ideal human or divine form.

Aristotle's Hylomorphism and Artistic Creation

Aristotle, Plato's student, offered a more integrated view. In works like Physics and Metaphysics, he introduced the concept of hylomorphism – that every substance is a compound of matter (hyle) and form (morphe). For Aristotle, form is not separate but inherent in the matter, giving it its specific nature and purpose (telos).

- Art as Actualization: Applied to art, this means the artist doesn't just copy, but imposes or actualizes a form in matter. The potter shapes clay into a vessel; the playwright crafts narrative and character into a coherent plot. The Form of the tragedy, as discussed in Poetics, is its structure, its beginning, middle, and end, leading to catharsis. Here, the artist is not merely duplicating reality but creating a new reality, guided by an internal understanding of what that form should be. This creative act is a manifestation of human intelligence and skill, bringing potential into actuality.

Beauty as a Manifestation of Form

The concept of Beauty is inextricably linked to Form. Throughout the Great Books, beauty is often described in terms of harmony, proportion, order, and coherence – qualities that are inherently structural or formal.

- Classical Beauty and Proportion: From the mathematical ratios explored by Pythagoras to the architectural principles of Vitruvius, classical thought often equated beauty with precise, discernible relationships and symmetries. A beautiful object possessed an internal logic, a Quality of being rightly ordered. This objective aspect of beauty suggests that certain forms inherently evoke aesthetic pleasure due to their intrinsic structure.

- The Subjective Dimension of Appreciation: While classical views often emphasized objective criteria, later philosophers, notably Kant in his Critique of Judgment, explored the subjective experience of beauty. For Kant, the judgment of beauty involves a "free play" of the imagination and understanding, leading to a feeling of pleasure that is "disinterested" and yet demands universal assent. Even here, the apprehension of form, albeit a form that harmonizes with our cognitive faculties, is central. The Quality of beauty, in this sense, lies in its capacity to resonate with our deepest sense of order and purpose.

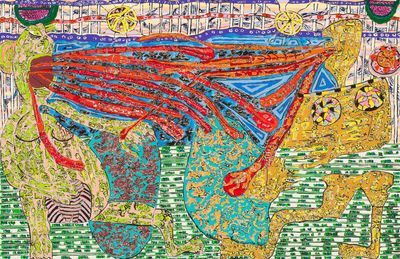

(Image: A detailed classical Greek sculpture, perhaps the Laocoön Group, depicting intricate human forms in dynamic tension. The marble shows exquisite detail in musculature and drapery, conveying both suffering and heroic struggle. The composition is a masterful arrangement of intertwined bodies, demonstrating a profound understanding of anatomical form, narrative, and emotional expression within a singular, unified artistic statement.)

The Pursuit of Quality in Artistic Expression

How do we distinguish great Art from mere craft, or a profound aesthetic experience from a fleeting impression? This brings us to the concept of Quality. Quality in art is not simply about technical skill, but about the effectiveness with which Form is realized and its capacity to convey Beauty or truth.

Craft, Truth, and the Enduring Value of Art

- Aristotle's Four Causes: Aristotle's framework of four causes can be illuminating here. The material cause (the bronze, the paint), the efficient cause (the artist), the formal cause (the design, the structure), and the final cause (the purpose, the effect on the audience). High Quality art excels in integrating all these causes: the chosen material serves the form, the artist skillfully executes the vision, the form is coherent and meaningful, and it achieves its intended purpose – whether to delight, instruct, or provoke catharsis.

- Hegel and the Spirit of Art: Hegel, in his Lectures on Aesthetics, viewed art as a manifestation of Spirit (Geist) in sensuous form. The Quality of art, for Hegel, lay in its ability to express profound spiritual or philosophical truths appropriate to its historical epoch. From the symbolic art of the East to the classical ideal and the romantic expression, each form of art strives to embody a deeper meaning. The enduring Quality of a work, therefore, is tied to its capacity to reveal something essential about human existence or consciousness.

- The Test of Time: Ultimately, the Quality of art is often measured by its lasting impact and relevance. Works that transcend their immediate context, continuing to speak to new generations, possess an inherent Quality that suggests a successful realization of Form and a profound expression of Beauty. They offer not just fleeting pleasure, but enduring insight.

Here are some elements contributing to artistic quality:

- Coherence: The internal consistency and logical arrangement of elements.

- Expressiveness: The power to evoke emotion, thought, or sensation.

- Originality: The unique vision or approach brought by the artist.

- Integrity: The faithfulness of the work to its own internal logic and purpose.

- Mastery: The technical skill and command over the chosen medium.

Art, Form, and the Human Condition

The philosophical inquiry into the nature of art and form is not an academic exercise divorced from life; it is deeply intertwined with the human condition. Our innate desire to create, to find beauty, and to impose order on chaos speaks to a fundamental aspect of being human. Through art, we not only reflect the world but also shape our understanding of it. The constant striving for Quality in artistic endeavor is a reflection of our own pursuit of meaning and excellence. By engaging with art, we engage with perfected forms, glimpsing ideals that elevate our spirit and deepen our appreciation for the intricate structure of reality itself.

YouTube: "Plato Aristotle Aesthetics"

YouTube: "Kant Hegel Philosophy of Art"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Nature of Art and Form philosophy"