The Nature of Art and Form: An Enduring Philosophical Inquiry

From the earliest cave paintings to the most avant-garde installations, humanity has grappled with the essence of art. But what truly defines it? This exploration delves into the profound relationship between art and form, tracing their philosophical lineage through the wisdom contained within the Great Books of the Western World. We will consider how form not only structures artistic expression but also shapes our perception of beauty and determines the very quality of a work, inviting us to ponder the deeper truths art seeks to reveal.

The Architectonics of Form: From Ideal to Embodied

The concept of form is foundational to Western philosophy, perhaps most famously articulated by Plato. For Plato, Forms were not mere shapes but eternal, immutable, and perfect blueprints existing in a realm beyond our sensory experience – the true reality of which our world is but a shadow. When an artist creates, are they merely imitating these shadows, as Plato sometimes suggested, or are they striving to capture a glimpse of these higher Forms?

Aristotle, while departing from Plato's transcendental Forms, nevertheless placed immense importance on form. For him, form was not separate from matter but inherent within it, providing the structure and essence that actualizes potential. A sculptor, in Aristotle's view, imposes a form (e.g., the form of a human figure) upon matter (stone), thereby bringing something new into being. This distinction sets the stage for centuries of debate about the artist's role. Is art a pale imitation, or a powerful act of bringing form into existence?

Art as Mimesis or Creative Act: A Timeless Debate

The question of whether art is primarily an imitation (mimesis) or a creative act has profound implications for its perceived value and quality. Plato, in his Republic, famously cast suspicion upon poets and artists, viewing their creations as twice removed from ultimate truth – an imitation of an imitation. A painted bed, for instance, is merely an imitation of a carpenter's bed, which itself is an imperfect copy of the ideal Form of a bed. From this perspective, art can be seen as deceptive, appealing to emotion rather than reason.

Aristotle, however, offered a robust defence of art in his Poetics. While acknowledging art as a form of mimesis, he argued that it is not a mere slavish copy of particulars but rather an imitation of actions and characters that reveals universal truths. Tragedy, for example, through its carefully constructed form and plot, can evoke catharsis and provide insights into the human condition that are more philosophical than mere historical accounts. Here, the artist doesn't just copy; they select, arrange, and give form to experience, creating a new whole that illuminates reality. This creative imposition of form is central to its quality.

The Pursuit of Beauty: Form's Highest Expression

Few concepts are as intertwined with art as beauty, and it is through the lens of form that we often apprehend it. What makes something beautiful? Is it a subjective feeling, or does beauty possess an objective form that we recognize? Plato, again, posited a transcendent Form of Beauty itself, suggesting that all beautiful things participate in this ultimate ideal. The beauty of a perfectly proportioned statue or a harmonious piece of music hints at this higher Form.

Later thinkers, such as Immanuel Kant, delved into the nature of aesthetic judgment, arguing that our experience of beauty involves a "purposiveness without purpose." We perceive form as having an internal harmony and coherence, as if it were designed for a specific end, even if that end is not explicitly stated. The form of a classical Greek temple, with its precise ratios and symmetrical elements, evokes a sense of order and balance that many find inherently beautiful. The quality of this beauty is often tied directly to the mastery of its form.

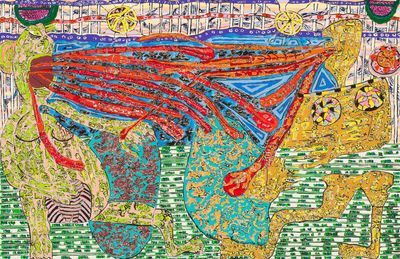

(Image: A detailed classical Greek sculpture, perhaps the Laocoön Group or Discobolus, depicting muscular human forms in dynamic tension or graceful poise. The marble is rendered with exquisite detail, highlighting the interplay of light and shadow across the sculpted anatomy, emphasizing the idealization of human form and the pursuit of beauty through precise composition and anatomical quality. The figures convey a sense of timeless struggle or athletic grace, inviting contemplation on the perfect form and the human condition.)

Defining Quality: The Metrics of Artistic Excellence

If form is the structure and beauty its highest expression, how then do we assess the quality of an artwork? This is perhaps one of the most contentious questions in aesthetics. Is quality an objective measure, or is it entirely in the eye of the beholder?

Philosophers and critics throughout history have proposed various criteria for judging artistic quality, often implicitly or explicitly tied to the effectiveness of its form:

- Technical Mastery: The skill with which the artist manipulates their chosen medium and imposes form. Think of the flawless brushwork of a Renaissance master or the intricate carving of a Baroque sculptor.

- Originality and Innovation: The artist's ability to create new forms or to express familiar ones in novel ways, pushing the boundaries of convention.

- Coherence and Unity: How well all elements of the form work together to create a unified and meaningful whole. Aristotle's emphasis on plot unity in tragedy is a prime example.

- Emotional Resonance: The capacity of the art to evoke profound feelings or intellectual contemplation in the audience, often achieved through deliberate choices in form.

- Truthfulness or Insight: The degree to which the art reveals deeper truths about human experience, society, or the natural world, even if through fictional forms.

Ultimately, the assessment of quality is a complex interplay of these factors, often filtered through cultural contexts and individual sensibilities. Yet, the underlying constant remains the artist's engagement with form – its creation, manipulation, and presentation.

The Enduring Dialogue on Art and Form

The relationship between art and form is not a static one, but a dynamic and evolving dialogue that continues to challenge and inspire. From Plato's ideal Forms to Aristotle's embodied forms, from the pursuit of objective beauty to the subjective experience of quality, the Great Books of the Western World provide an inexhaustible wellspring of insight into these fundamental questions. To truly appreciate art is to understand its inherent structure, to perceive the form that gives it life, and to recognize the profound ways in which it reflects, shapes, and enriches our understanding of reality itself.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato's Theory of Forms Explained"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Philosophy of Art and Beauty: An Introduction"