The Cosmic Dance: Philosophical Inquiries into the Mechanics of Planetary Motion

The seemingly predictable ballet of planets across the night sky has captivated human thought for millennia. What began as a source of myth and wonder evolved into a rigorous scientific pursuit, yet the philosophical questions underpinning this cosmic dance have never truly faded. This pillar page delves into the fascinating journey of understanding planetary mechanics, tracing its evolution from ancient philosophical conjectures to the sophisticated mathematical models of modern Physics and Astronomy. We will explore how humanity's quest to quantify and explain celestial movements has profoundly shaped our understanding of reality, causality, and the very nature of knowledge itself. It's not merely about orbits and gravitational pulls; it's about how we define order, chaos, and our place within the grand, unfolding universe.

From Celestial Spheres to Epicycles: Early Philosophical Models of the Cosmos

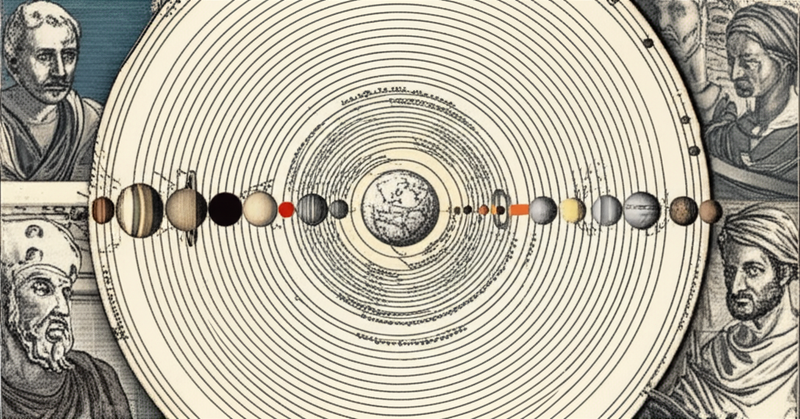

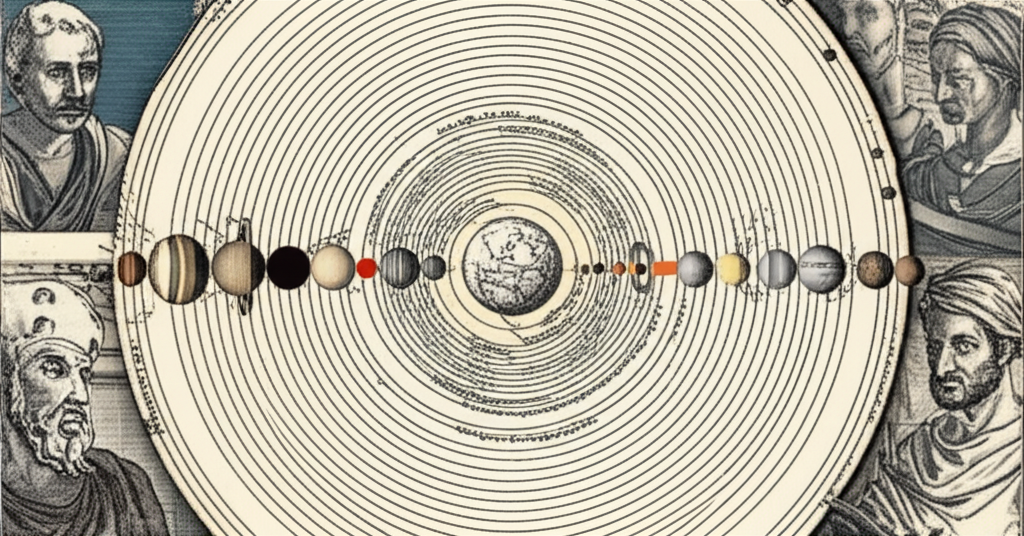

Before telescopes and calculus, the heavens were primarily a domain of philosophical speculation, where observation mingled with a profound desire for order and perfection. Ancient thinkers sought to explain the erratic paths of planets (the "wanderers") within a harmonious, geocentric universe.

Plato and Aristotle: The Quest for Perfect Circles

For ancient Greek philosophers, the cosmos was a realm of divine order and geometric purity. Plato, in his Timaeus, posited a demiurge who crafted the universe according to mathematical principles, with celestial bodies moving in perfect circles—the most ideal form. This philosophical predisposition influenced subsequent astronomical models for centuries.

Aristotle, further developing this geocentric view in works like his Metaphysics, described a universe composed of concentric, crystalline spheres. Each sphere, driven by an unmoved mover, carried a celestial body, moving it in a uniform circular motion around a stationary Earth. This system was aesthetically pleasing and philosophically coherent, providing a comprehensive worldview where the terrestrial and celestial realms operated under different, yet divinely ordained, mechanics. The quantity of spheres increased as observations became more refined, attempting to account for the observed irregularities.

Ptolemy's Almagest: A Masterpiece of Observation and Complexity

By the 2nd century CE, the limitations of simple concentric spheres became apparent. Claudius Ptolemy, building upon centuries of Babylonian and Greek astronomical data, synthesized the geocentric model into its most sophisticated form in his monumental work, the Almagest.

Ptolemy ingeniously introduced concepts like epicycles (small circles whose centers moved along larger circles called deferents), eccentrics (circles whose centers were offset from the Earth), and equants (points from which the angular motion of a planet appeared uniform). This system, while incredibly complex, allowed for remarkably accurate predictions of planetary positions. It was a triumph of observational Astronomy and mathematical ingenuity, demonstrating how a system could be made to work by increasing the quantity of its components, even if its underlying philosophical premise (geocentrism) was ultimately flawed. The Almagest became the authoritative text on Astronomy for over 1,400 years, a testament to its predictive power and the philosophical framework it supported.

| Philosophical Model | Key Features | Central Tenet | Philosophical Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platonic/Aristotelian | Concentric spheres, perfect circles, uniform motion | Geocentric | Divine order, geometric perfection, qualitative reasoning |

| Ptolemaic | Epicycles, deferents, eccentrics, equants | Geocentric | Predictive accuracy, mathematical complexity, fitting observations to a preconceived structure |

Re-centering the Universe: Copernicus, Kepler, and the Dawn of Modern Mechanics

The medieval period saw the Ptolemaic system refined but not fundamentally challenged within the Western intellectual tradition. However, the seeds of a profound revolution were being sown, driven by a desire for greater simplicity and predictive accuracy.

Copernicus's De Revolutionibus: A Bold Hypothesis

Nicolaus Copernicus, a Polish astronomer, dared to propose a radical alternative in his De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), published posthumously in 1543. His heliocentric model placed the Sun, not the Earth, at the center of the universe, with the Earth and other planets orbiting it. This shift, while initially offering only marginal improvements in predictive accuracy over Ptolemy's system, had monumental philosophical implications. It demoted Earth from its privileged central position, challenging centuries of theological and philosophical dogma. The beauty of Copernicus's system lay in its elegance and the reduction in the quantity of epicycles needed, appealing to an aesthetic sense of cosmic order. This was a critical step in the development of modern Astronomy and the shift towards a more empirical, less anthropocentric understanding of the cosmos.

Kepler's Laws: Unveiling the Elliptical Truth

Johannes Kepler, a German mathematician and astronomer, inherited the meticulous observational data of Tycho Brahe. Through decades of painstaking calculation, Kepler abandoned the ancient dogma of perfect circles, recognizing that planets moved in ellipses. His three laws of planetary motion, published between 1609 and 1619, revolutionized the understanding of celestial mechanics:

- Law of Ellipses: Planets orbit the Sun in elliptical paths, with the Sun at one focus.

- Law of Equal Areas: A line segment joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time.

- Law of Harmonies: The square of the orbital period of a planet is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit.

Kepler's laws were a triumph of empirical data over philosophical prejudice. They demonstrated that the universe operated not on ideal forms, but on precise mathematical relationships derived from observation. This marked a crucial transition from qualitative philosophical Astronomy to quantitative Physics, emphasizing the importance of precise quantity and measurement in understanding the cosmos.

The Grand Unification: Newton, Gravity, and the Mathematical Universe

The work of Copernicus and Kepler paved the way for the most profound synthesis in the history of Physics and Astronomy: Isaac Newton's universal law of gravitation.

Principia Mathematica: A Triumph of Physics and Quantity

In his monumental Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), published in 1687, Isaac Newton presented a unified theory of motion and gravity that explained both terrestrial and celestial mechanics. He demonstrated that the same force that caused an apple to fall to Earth also governed the orbits of the planets around the Sun, and the Moon around the Earth.

Newton's three laws of motion, combined with his law of universal gravitation, provided a comprehensive and incredibly accurate framework for understanding the universe. He showed that every particle of matter attracts every other particle with a force proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers. This was a profound conceptual leap, establishing Physics as the dominant paradigm for explaining natural phenomena. The Principia showcased the immense power of mathematics to describe the natural world, elevating quantity from a mere descriptor to the fundamental language of the universe's operation.

Philosophical Repercussions: Determinism and the Clockwork Universe

Newton's success had profound philosophical repercussions. The universe, governed by precise, immutable laws, began to be seen as a grand, deterministic clockwork machine. If all forces and initial conditions were known, the future state of the universe could, in principle, be predicted with absolute certainty. This raised questions about free will, the role of divine intervention, and the nature of causality. While Newton himself was deeply religious and saw God as the ultimate clockmaker, subsequent philosophers wrestled with the implications of a universe that seemed to operate without constant divine tinkering. The mechanics of planetary motion, once a mystery, now seemed a perfectly understood, quantifiable system.

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Newtonian mechanics philosophy" or "Great Books of the Western World Newton Principia""

Modern Perspectives: Einstein and the Fabric of Spacetime

Even Newton's grand synthesis, while breathtakingly successful, was not the final word. The turn of the 20th century brought new challenges and a deeper understanding of the universe's fundamental mechanics.

Challenging Absolutes: Einstein's Relativistic Universe

Albert Einstein's theories of special and general relativity, developed in the early 20th century, revolutionized our understanding of space, time, gravity, and the very fabric of the cosmos. General relativity, in particular, redefined gravity not as a force acting at a distance, but as a curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy. Planets don't orbit the Sun because of an invisible pull, but because they are following the shortest path through the curved spacetime around the Sun.

This new understanding of Physics further intertwined Astronomy with fundamental questions about the nature of reality. Concepts like absolute space and time, foundational to Newtonian mechanics, were discarded, replaced by a dynamic, interconnected spacetime. The quantity of dimensions and the nature of their interaction became more complex, pushing the boundaries of both scientific and philosophical inquiry.

The Enduring Philosophical Questions

Even with the incredible advancements in Physics and Astronomy, the study of planetary mechanics continues to pose profound philosophical questions:

- Does the universe have a fundamental, discoverable order, or are our laws merely approximations of an inherently chaotic reality?

- What are the limits of human knowledge and our ability to quantify and predict cosmic phenomena?

- How do our scientific models influence our metaphysical beliefs about free will, determinism, and the existence of a higher power?

- What does the ongoing evolution of our understanding mean for the stability of scientific truth?

The quest to understand the mechanics of the cosmos is an endless journey, continually refining our scientific models while simultaneously deepening our philosophical wonder.

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Philosophy of General Relativity" or "Einstein's theory of gravity explained philosophically""

Conclusion: The Cosmic Mirror

The journey from mythical narratives to the mathematical precision of modern Physics in understanding planetary mechanics is a testament to the enduring power of human intellect and curiosity. From the ancient Greek philosophers who sought perfect circles to Kepler's elliptical breakthroughs, and from Newton's universal gravity to Einstein's curved spacetime, our understanding of Astronomy has continually evolved.

This exploration reveals that the study of celestial mechanics is inextricably linked with fundamental philosophical questions about order, causality, and the nature of quantity and reality itself. Each scientific advancement has not only explained how the planets move but has also forced us to re-evaluate what it means to be human in a vast and complex universe. The cosmos, in its grand, silent dance, continues to be a profound teacher, not just of mechanics, but of our own capacity for wonder, inquiry, and the relentless pursuit of knowledge.

I encourage you to delve into the original texts of the "Great Books of the Western World"—from Plato and Aristotle to Newton—to experience these profound intellectual shifts firsthand and ponder the cosmic questions that continue to resonate through the ages.