The Enduring Dance of Thought: Unpacking the Logic of Universal and Particular

A Foundation for Rigorous Reasoning

The distinction between the Universal and Particular lies at the very heart of sound Logic and philosophical inquiry. It is a fundamental framework that allows us to organize our thoughts, make sense of the world, and construct coherent arguments. Simply put, universals refer to general concepts, categories, or properties that can apply to many individual things, while particulars are the specific, individual instances of those concepts. Understanding this distinction is crucial for accurate Definition and effective Reasoning, guiding us from specific observations to general truths, and vice versa. Without grasping this interplay, our attempts at understanding reality, from the simplest observation to the most complex philosophical system, would crumble into confusion.

The Bedrock of Western Thought

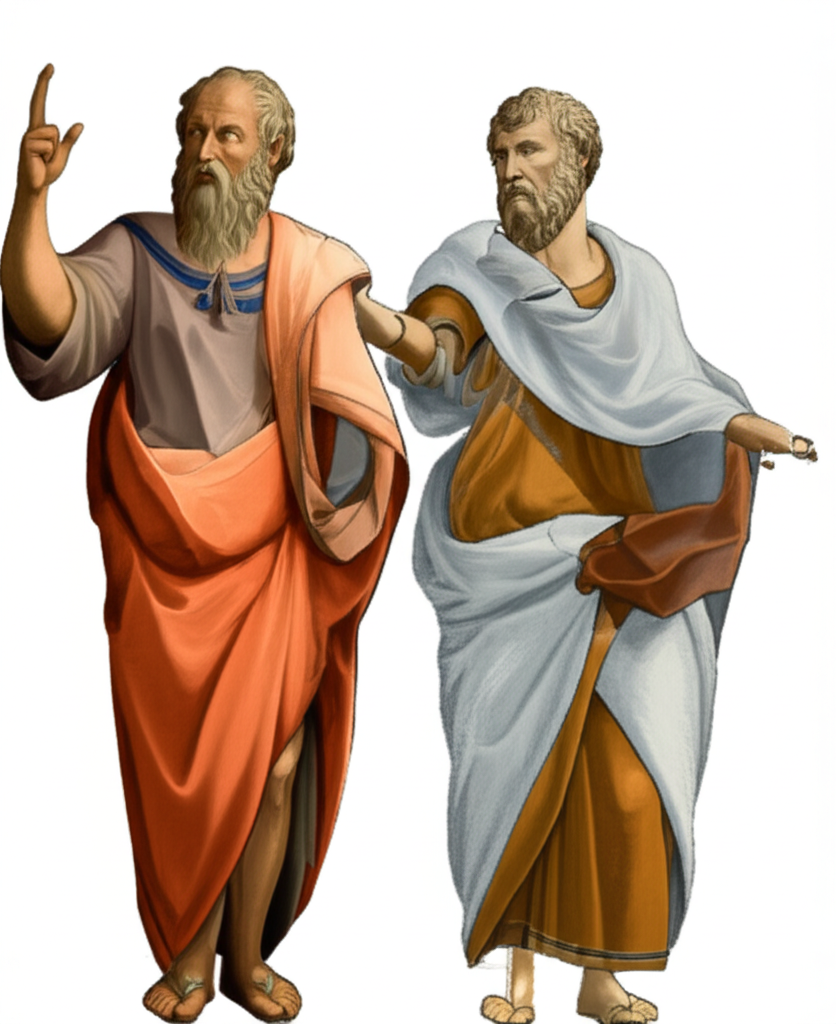

From the ancient Greeks, whose dialogues and treatises form the bedrock of the Great Books of the Western World, philosophers have grappled with the nature and relationship of the universal and the particular. Plato, with his world of Forms, posited universals as eternal and perfect archetypes existing independently of the physical world. Aristotle, while acknowledging universals, grounded them within the particular things themselves, seeing them as immanent properties. This enduring philosophical debate highlights the profound significance of these concepts, not merely as abstract categories, but as essential tools for dissecting reality.

Defining Our Terms: What's What?

To engage in meaningful Reasoning, we must first establish clear Definition for our terms. The Universal and Particular are not merely academic jargon but represent two distinct modes of apprehending existence.

-

The Universal:

- Refers to a general concept, quality, or relation.

- Applies to many individual instances.

- Examples: "humanity," "redness," "justice," "cat."

- Often expressed through general terms or abstract nouns.

- It is what common things share.

-

The Particular:

- Refers to a specific, individual entity or instance.

- Applies to one unique thing.

- Examples: "Socrates," "this specific apple," "the act of giving to charity yesterday," "my cat, Whiskers."

- Often expressed through proper nouns or demonstrative pronouns (e.g., "this," "that").

- It is the individual thing itself, existing in a specific time and place.

Consider the statement: "All humans are mortal." "Humans" is a universal term, referring to the species. "Mortal" is also a universal predicate, a quality that applies to all members of that species. If we then say, "Socrates is human," "Socrates" is a particular individual. The Logic of the syllogism then allows us to deduce the particular conclusion: "Therefore, Socrates is mortal."

The Dynamic Duo in Reasoning

The interplay between the Universal and Particular is fundamental to all forms of Reasoning:

-

Deductive Reasoning (from Universal to Particular):

- Starts with a general principle (universal premise) and applies it to a specific case (particular instance) to reach a specific conclusion.

- Example:

- All birds have feathers. (Universal)

- A robin is a bird. (Particular instance of a universal)

- Therefore, a robin has feathers. (Particular conclusion)

- This form of Logic guarantees the truth of the conclusion if the premises are true.

-

Inductive Reasoning (from Particular to Universal):

- Starts with specific observations or instances (particulars) and moves towards a general conclusion or principle (universal).

- Example:

- This swan is white. (Particular observation)

- That swan is white. (Another particular observation)

- ... (Many more observations of white swans) ...

- Therefore, all swans are white. (Universal conclusion, though potentially fallible)

- While not guaranteeing truth, induction is how we form hypotheses, develop theories, and learn from experience. It is the engine of scientific discovery and everyday learning.

The ability to navigate between these two poles of thought is a hallmark of sophisticated Reasoning. We constantly use particulars to build our understanding of universals, and then use those universals to interpret and predict new particulars.

The Philosophical Weight of Definition

The problem of universals—the question of whether universals exist independently of our minds, and if so, how—has occupied thinkers for millennia. Is "redness" a real thing, or just a concept we apply to many red objects? How we answer this question profoundly impacts our metaphysics, epistemology, and even ethics.

For instance, when we speak of "justice" (a universal), are we referring to an ideal form, or merely to the collection of just acts (particulars) we observe? Our Definition of such abstract concepts is heavily influenced by our philosophical stance on the nature of universals. This makes the distinction not just a tool for formal Logic, but a lens through which we construct our entire worldview.

Conclusion: The Indispensable Framework

The Logic of Universal and Particular is not an arcane philosophical curiosity but a vital cognitive framework. It underpins our capacity for coherent thought, precise Definition, and effective Reasoning. From the simple act of categorizing objects to the grandest philosophical debates about the nature of reality, the dynamic interplay between the general and the specific guides our understanding. To neglect this fundamental distinction is to invite confusion and undermine the very foundation of our intellectual pursuits.

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Aristotle Logic Universal Particular"

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Problem of Universals Explained"