The Enduring Blueprint: Unpacking Plato's Idea of Form (Eidos) in Metaphysics

Plato's theory of Forms, or Eidos, stands as a cornerstone of Western Metaphysics, proposing that beyond the fleeting, imperfect world we perceive, there exists a realm of perfect, eternal, and unchanging archetypes. These transcendent Forms are the true reality, serving as the models for everything we encounter in our sensory experience, and providing a powerful solution to the philosophical problem of Universal and Particular.

Unveiling Plato's Realm of Perfect Ideas

In the grand tapestry of philosophical inquiry, few concepts have cast as long a shadow or sparked as much debate as Plato's theory of Forms, or Eidos. This profound contribution to Metaphysics, meticulously explored in the volumes of the Great Books of the Western World, offers a radical perspective on the nature of reality itself, challenging us to look beyond the immediate and the tangible. For Plato, the world we inhabit, with all its beautiful but transient objects, is merely a shadow play, an imperfect imitation of a more perfect, more real dimension.

Defining the Eidos: What are Plato's Forms?

At its heart, the Idea of Form posits that for every quality, object, or concept we perceive—be it beauty, justice, a tree, or a circle—there exists a perfect, non-physical, and unchanging archetype in a transcendent realm. These are the Forms (from the Greek eidos or idea), and they are not merely mental constructs but objective, independently existing entities.

Consider a beautiful painting. We might call it beautiful, but it will eventually fade, tear, or be destroyed. Its beauty is fleeting. Plato would argue that the painting is beautiful because it participates in, or imitates, the Form of Beauty itself – an eternal, perfect, and absolute standard of beauty that exists independently of any particular beautiful object.

Key Characteristics of the Forms:

Plato endowed his Forms with several crucial attributes that distinguish them from the objects of our sensory world:

- Transcendence: Forms exist outside of space and time. They are not physical objects and cannot be perceived by our senses.

- Purity/Perfection: Each Form is the perfect embodiment of the quality or object it represents. The Form of a Circle, for instance, is perfectly circular, unlike any physical circle we might draw.

- Immutability: Forms are unchanging and eternal. They do not come into being or pass away.

- Intelligibility: Forms are grasped by the intellect, not by the senses. True knowledge (episteme) is knowledge of the Forms.

- Causality: Forms are the cause of the being and characteristics of the particulars in the physical world. A particular chair is a chair because it participates in the Form of Chair.

The Problem of Universal and Particular

One of the most enduring problems in Metaphysics that Plato's theory directly addresses is the relationship between the Universal and Particular. How is it that many different individual objects can share the same quality or be of the same kind?

- Particulars: These are the individual, concrete objects we experience—this specific red apple, that particular just act, the unique human standing before us. They are many, changing, and imperfect.

- Universals: These are the general qualities or categories that many particulars share—"redness," "justice," "humanity." How do these universals exist, and where do they reside if not in the particulars themselves?

Plato's Forms provide an elegant solution. The Universal (e.g., "redness") exists as a perfect, singular Form (the Form of Redness) in the transcendent realm. The Particulars (individual red apples, red cars, red shirts) are "red" because they participate in or imperfectly reflect this singular Form. This participation explains how multiple, distinct objects can share a common essence without the essence itself being fragmented or replicated imperfectly within each object.

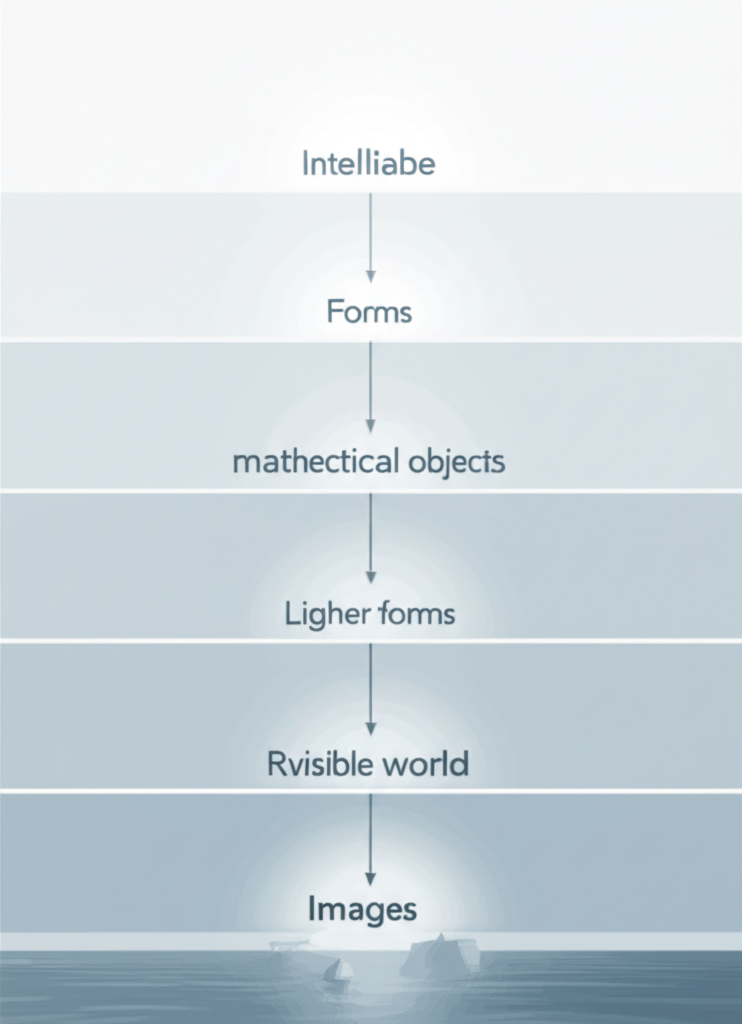

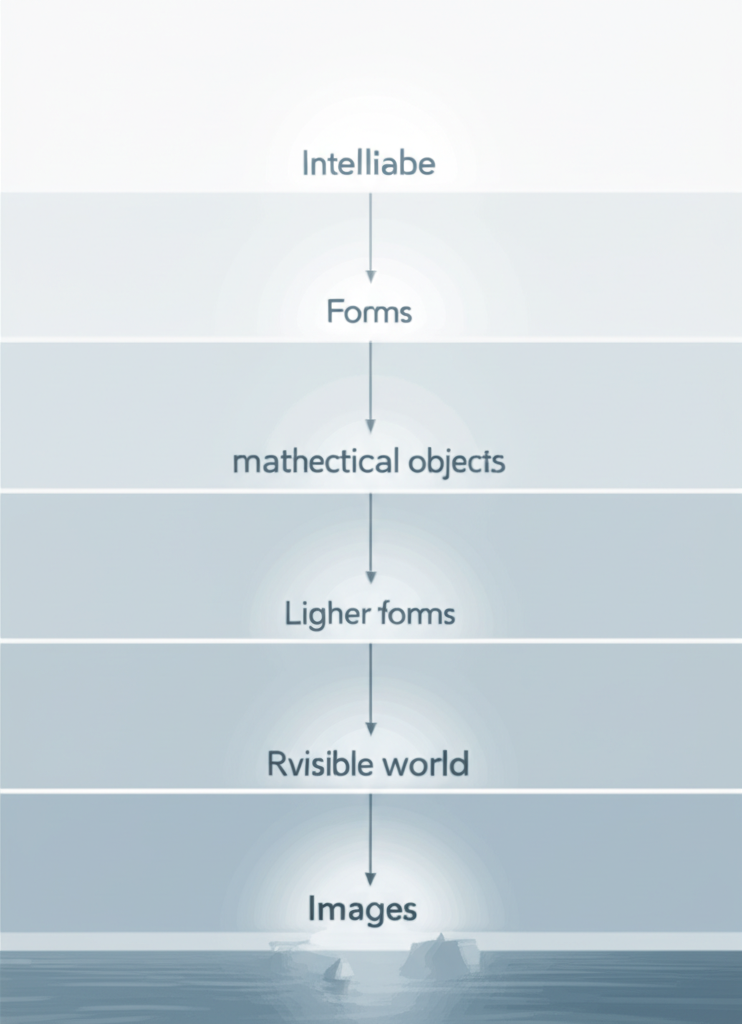

, while the top two sections illustrate the intelligible world (mathematical objects and the Forms). Arrows indicate the progression from opinion to knowledge, culminating in the Form of the Good at the very top. The drawing style is classical, reminiscent of ancient Greek pottery or philosophical diagrams, with clear labels for each section.)

, while the top two sections illustrate the intelligible world (mathematical objects and the Forms). Arrows indicate the progression from opinion to knowledge, culminating in the Form of the Good at the very top. The drawing style is classical, reminiscent of ancient Greek pottery or philosophical diagrams, with clear labels for each section.)

Illustrative Examples from the Great Books

Plato masterfully illustrates these complex ideas through allegories and analogies in his dialogues, especially within the Republic.

- The Allegory of the Cave: This famous allegory vividly portrays our sensory world as a cave where prisoners are chained, mistaking shadows for reality. True reality, the Forms, lies outside the cave, illuminated by the sun (the Form of the Good).

- The Divided Line: This analogy further articulates the different levels of reality and corresponding types of knowledge, moving from mere opinion about images and physical objects to true understanding of mathematical concepts and, ultimately, the Forms themselves.

These examples from the Great Books of the Western World are not just literary devices; they are pedagogical tools designed to guide the reader towards a deeper philosophical insight into the nature of existence and knowledge.

The Enduring Legacy of Forms

Plato's Idea of Form has profoundly influenced Western thought, laying the groundwork for much of subsequent Metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics. While later philosophers, including his own student Aristotle, offered critiques and alternative theories, the Platonic Forms continue to resonate. They compel us to question the nature of reality, the source of knowledge, and the ultimate standards of truth, beauty, and goodness. The search for Universals and their relationship to Particulars remains a central concern, underscoring the enduring power of Plato's original insight.

YouTube: "Plato's Theory of Forms explained"

YouTube: "Platonic Forms and the Problem of Universals"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Idea of Form (Eidos) in Metaphysics philosophy"