The Enduring Blueprint: Exploring the Idea of Form (Eidos) in Metaphysics

The concept of Form, or Eidos as it was known in ancient Greek, stands as a cornerstone in the edifice of Western Metaphysics. At its core, the Idea of Form posits that beyond the fleeting, ever-changing world of our senses, there exists a realm of perfect, eternal, and unchanging essences that give reality to everything we perceive. This foundational notion, most famously articulated by Plato, seeks to answer profound questions about the nature of reality, knowledge, and existence, particularly addressing the relationship between the Universal and Particular.

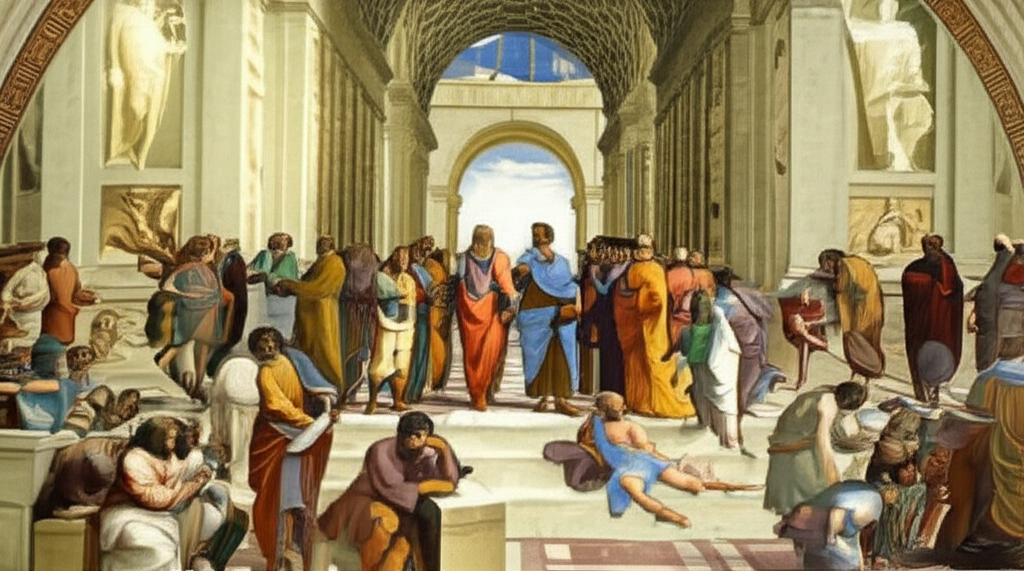

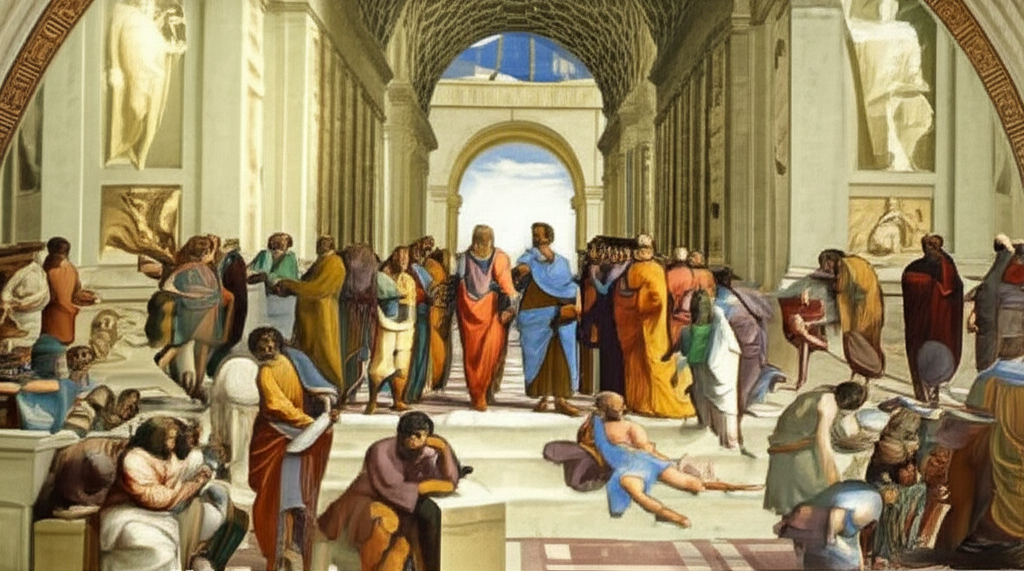

Plato's Realm of Perfect Forms

For Plato, the world we inhabit, with its myriad objects and experiences, is merely a shadow or imperfect reflection of a higher reality: the World of Forms. He argued that for anything to be truly known or even to exist, there must be an underlying, immutable standard. This standard is the Form.

What are Platonic Forms?

Plato's Forms are not mere mental concepts or ideas in our heads; they are objective, mind-independent entities that constitute the true reality. Consider a beautiful sunset or a just act. While these particular instances may vary, Plato argued there must be a singular, perfect Form of Beauty and a Form of Justice, respectively, from which all beautiful things and just acts derive their essence.

Here are the key characteristics of Plato's Forms:

- Eternal and Unchanging: Forms exist outside of time and space, never coming into being or perishing, never altering their nature.

- Perfect and Ideal: They represent the ultimate, unadulterated essence of a thing, serving as the perfect blueprint for all particulars.

- Non-physical and Transcendent: Forms exist in a separate, intelligible realm, accessible only through intellect and reason, not through the senses.

- Knowable through Intellect: True knowledge (episteme) is of the Forms, while sensory experience (doxa) provides only opinion about particulars.

- Cause of Being and Knowledge: Particular objects and concepts "participate" in or "imitate" the Forms, thereby acquiring their characteristics and making them knowable.

Universal vs. Particular in Plato's Thought:

| Aspect | Universal (Form/Eidos) | Particular (Sensible Object) |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Perfect, unchanging, eternal essence | Imperfect, changing, temporal instance |

| Realm | Intelligible World (World of Forms) | Sensible World (World of Appearances) |

| Source | True reality, source of existence and intelligibility | Derives reality from participation/imitation of Forms |

| Example | The Form of "Redness" | A specific red apple, a particular red car |

This distinction between the Universal (the Form) and the Particular (the individual instance) was Plato's elegant solution to how we can recognize commonalities amidst endless diversity. How do we know that different individual chairs are all "chairs"? Because they all partake in the Form of Chair.

Aristotle's Immanent Forms

While greatly influenced by his teacher Plato, Aristotle offered a significant revision to the Idea of Form. Aristotle found the notion of Forms existing in a separate, transcendent realm problematic. He questioned how a Form, entirely separate from the material world, could truly be the cause or essence of things within it.

Form and Matter: The Hylomorphic Compound

For Aristotle, Form is not separate from matter; rather, it is immanent within it. He proposed the concept of hylomorphism, where every physical object is a compound of two intrinsic principles:

- Matter (hyle): The raw potential, the "stuff" out of which something is made (e.g., wood for a table).

- Form (eidos): The actualizing principle, the structure, organization, or essence that makes the matter what it is (e.g., the "tableness" that makes the wood a table).

In this view, the Form is the Universal essence that defines a thing, but it exists within the Particular object. A chair’s Form is its structure and function, which makes it a chair, and this Form cannot exist independently of some matter (wood, metal, plastic) to embody it. The Form of "humanity" is the specific organization and capacities (like rationality) that make a particular collection of flesh and bone a human being.

The Enduring Legacy of Eidos

The debate ignited by Plato and Aristotle concerning the nature and location of Form—whether transcendent or immanent—has reverberated through Western philosophy for millennia. It continues to shape discussions in Metaphysics, epistemology, and even ethics. The Idea of Form, whether as a perfect blueprint in a separate realm or as the intrinsic essence of a thing, remains a powerful intellectual tool for understanding the structure of reality and the relationship between the Universal and Particular. It challenges us to look beyond mere appearances and ponder the deeper, underlying nature of existence itself.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato Theory of Forms explained"

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Aristotle Metaphysics Form and Matter"