The Hypotheses of the Origin of the World: A Philosophical Odyssey

From the earliest flickers of human consciousness, the question of our World's genesis has captivated minds. How did this vast expanse of stars, planets, and life come to be? This isn't merely a scientific query; it's a profound philosophical challenge that has shaped our understanding of existence, purpose, and our place in the cosmos. This pillar page embarks on a journey through the most influential hypothesises concerning the World's origin, tracing their evolution from ancient myths and philosophical speculations to the sophisticated models of modern astronomy, often drawing directly from the monumental intellectual efforts preserved in the Great Books of the Western World. We'll explore how each era, armed with its unique tools of observation and reason, sought to unravel the ultimate mystery, revealing not just different answers, but different ways of asking the question itself.

The Ancient Cosmos: Myth, Philosophy, and Early World Views

Before telescopes and particle accelerators, humanity relied on observation, intuition, and divine revelation to construct their cosmogonies. These early narratives, often steeped in myth, laid the groundwork for the philosophical inquiries that would follow.

-

From Chaos to Order: The Primordial Beginnings

Many ancient cultures conceived of a primordial state of chaos or nothingness from which order emerged. Hesiod's Theogony, for example, describes Chaos as the first entity, followed by Gaia (Earth) and Eros (Love), setting the stage for the birth of the gods and theWorldas we know it. These were not scientifichypothesises in the modern sense, but foundational stories that provided meaning and structure to existence. The Pre-Socratics, like Anaximander with his apeiron (the boundless infinite) or Thales with water as the primary element, began to abstract these origins into more philosophical principles, seeking a single, underlying substance or force. -

Plato's Demiurge: The Intelligent Craftsman

In his dialogue Timaeus, Plato presents a powerfulhypothesisfor theWorld's creation: the Demiurge. This divine craftsman, not an all-powerful creator ex nihilo, shapes a pre-existing, chaotic matter according to eternal, perfect Forms. TheWorldwe inhabit, therefore, is a beautiful but imperfect copy of an idealWorld. This introduces the notion of an intelligent designer and a teleological (purpose-driven) universe, a concept that would resonate for millennia. -

Aristotle's Unmoved Mover: An Eternal World and Its First Cause

Aristotle, in works like Physics and Metaphysics, offered a profoundly differenthypothesis. For him, theWorldwas eternal, without beginning or end. Change and motion were inherent, but required a first cause – an "Unmoved Mover" – that initiated all motion without itself being moved. This Mover was pure actuality, the ultimate end towards which all things strive, acting as a final cause rather than an efficient cause in the act of creation. Hisastronomyposited a geocentricWorldof concentric spheres, perfectly suited to the eternal, unchanging heavens. -

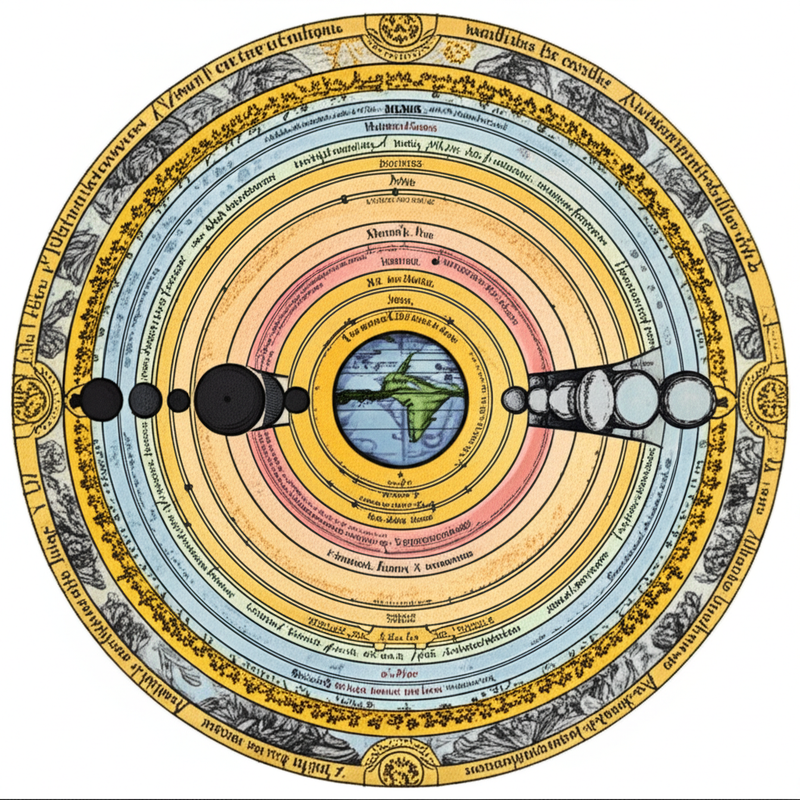

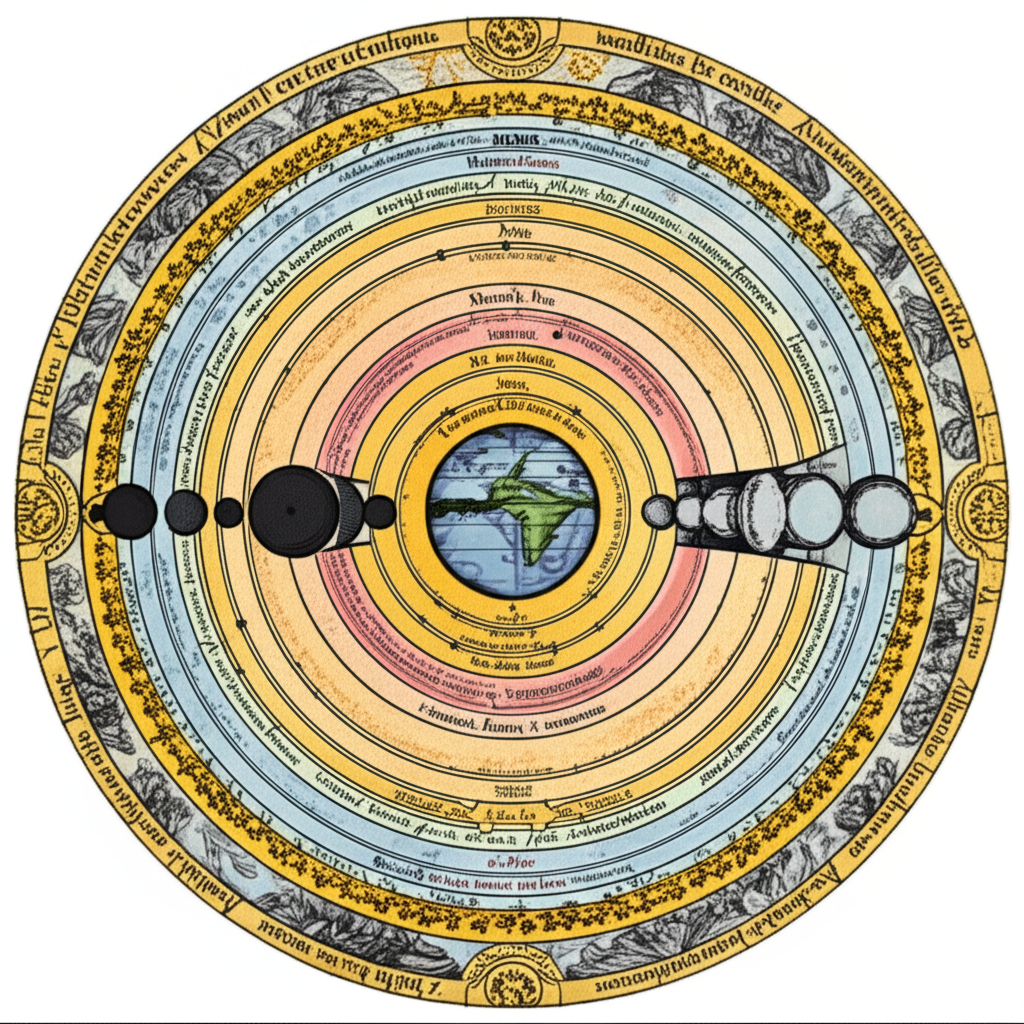

The Geocentric

Astronomy: Ptolemy's Enduring Model

Building upon Aristotle's cosmology, Claudius Ptolemy's Almagest solidified the geocentrichypothesis. His intricate model, with Earth at the center and planets moving in epicycles and deferents, provided an incredibly accurate predictive framework for celestial motions for over 1400 years. ThisWorldview, embraced by scholastic philosophy, perfectly integrated with prevailing theological doctrines, placing humanity firmly at the center of God's creation.

The Copernican Revolution and the Shifting World Picture

The Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution brought forth new tools of observation and a daring spirit of intellectual inquiry, fundamentally challenging the established geocentric World.

-

A New

Hypothesis: Copernicus Challenges theWorld's Center

Nicolaus Copernicus, in De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), proposed a radicalhypothesis: the Sun, not the Earth, was the center of theWorld. This heliocentric model, initially a mathematical convenience, possessed a profound philosophical implication: humanity was not at the physical center of the universe. This shift began to dismantle the anthropocentric bias that had underpinned much of Western thought. -

Galileo and the Telescopic Gaze: Empirical Observation

Galileo Galilei, with his telescope, provided empirical evidence that bolstered Copernicus'shypothesis. His observations of Jupiter's moons (a mini-solar system), the phases of Venus (like the Moon), and the imperfections of the Moon's surface, directly contradicted the Aristotelian-PtolemaicWorldview of perfect, unchanging celestial spheres. His Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems famously championed the Copernican model, highlighting the power of observation over pure deduction. -

Descartes and the Mechanistic Universe: A Clockwork

World

René Descartes, in works like Principles of Philosophy, offered a mechanistichypothesisfor theWorld's operation. He conceived of the universe as a vast machine, governed by precise, discoverable laws. God's role was primarily to set this machine in motion, after which it operated according to its own inherent principles. This paved the way for a scientific understanding of theWorldthat did not necessarily require constant divine intervention, focusing instead on matter and motion.

The Newtonian Synthesis and the Dawn of Modern Astronomy

Isaac Newton's monumental work brought a new level of mathematical precision and predictive power to our understanding of the World, laying the foundation for modern astronomy.

-

Laws of Motion and Universal Gravitation: A Predictable

World

In Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), Isaac Newton presented his universal law of gravitation and three laws of motion. This singlehypothesisexplained both the falling apple and the orbiting planets, unifying terrestrial and celestial mechanics. TheWorldwas now seen as a coherent, predictable system governed by immutable laws. -

The "Divine Watchmaker"

Hypothesis: God as the Ultimate Architect

Newton's laws, while describing the mechanics of the universe, did not necessarily preclude a divine origin. In fact, for many, the very order and precision of the NewtonianWorldimplied a divine intelligence. The "Divine Watchmaker"hypothesissuggested that God had designed and set in motion this perfect cosmic machine, much like a watchmaker designs and builds a complex timepiece. This perspective found its way into later philosophical and theological arguments. -

Kant's Nebular

Hypothesis: A Step Towards NaturalEvolutionof theWorld

Immanuel Kant, in his early work Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens, proposed a groundbreakinghypothesisfor the formation of the solar system: the nebularhypothesis. He suggested that the Sun and planets condensed from a rotating cloud of gas and dust. This was a crucial step, proposing a natural,evolutionary process for the formation of celestial bodies, moving away from instantaneous creation and towards a dynamicWorldthat developed over time according to physical laws.

The Evolution of Our World and Life: From Geology to Biology

The 18th and 19th centuries witnessed a profound shift in understanding the World's age and the evolution of life upon it, further challenging static views of creation.

-

Geological Time Scales: Unveiling the Ancient Earth

While not strictly "Great Books" in the same vein as Plato or Aristotle, the geological work of figures like Charles Lyell (principles of uniformitarianism) revolutionized the understanding of Earth's history. Hishypothesissuggested that the same geological processes we observe today have operated over vast spans of time, implying a much, much older Earth than previously imagined. This extended theWorld's timeline dramatically, providing the necessary canvas for the slow, incremental changes ofevolution. -

Darwin's

EvolutionaryHypothesis: The Origin of Species

Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species presented the powerfulhypothesisofevolutionby natural selection. While primarily focused on theevolutionof life on Earth rather than the Earth's origin itself, Darwin's work profoundly impacted the philosophical understanding of a dynamicWorld. It demonstrated that complex systems could arise from simpler ones through natural processes, without direct divine intervention at every step. This concept ofevolutionary change, applied to life, mirrored Kant's earlierhypothesisof theevolutionof the solar system, suggesting aWorldconstantly in flux. -

The Philosophical Implications of a Dynamic

World

The combined insights of geology and biology painted a picture of aWorldthat had undergone immense change over vast periods. This challenged notions of a static, perfectly createdWorldand forced philosophers to grapple with questions of contingency, adaptation, and the role of chance in the development of both the planet and its inhabitants.

Modern Cosmological Hypotheses: Echoes of Ancient Questions

While the "Great Books" primarily predate modern cosmology, the philosophical questions they raised resonate deeply with contemporary scientific hypothesises about the World's origin.

-

The Big Bang

Hypothesis: A ScientificWorldOrigin Story

The prevailing scientifichypothesisfor the universe's origin is the Big Bang. This model suggests that the universe began as an extremely hot, dense point approximately 13.8 billion years ago and has been expanding and cooling ever since. While a scientific theory, its implications – a universe with a definite beginning, emerging from a singular state – echo ancient philosophical and theological debates about creation ex nihilo and the nature of time itself. It provides a scientific "genesis" narrative for the entireWorld. -

The Anthropic Principle: Is the

WorldFine-Tuned?

Modernastronomyhas revealed that many fundamental physical constants and conditions in the universe seem remarkably "fine-tuned" for the emergence of life. This observation has given rise to the Anthropic Principle, ahypothesisthat suggests either our universe is just one of many (a multiverse), or there is some deeper reason for this apparent fine-tuning, perhaps even pointing back to a form of intelligent design, albeit on a cosmic scale. This brings us full circle to questions reminiscent of Plato's Demiurge or the Divine Watchmaker, re-contextualized by scientific discovery.

Conclusion: The Enduring Quest

The journey through the hypothesises of the World's origin is a testament to humanity's relentless curiosity and our profound desire for understanding. From the mythological narratives of chaos and creation to the philosophical constructs of the Demiurge and Unmoved Mover, and finally to the scientific models of nebular evolution and the Big Bang, each era has built upon, challenged, and reshaped our understanding. The Great Books of the Western World provide a rich tapestry of these intellectual struggles, demonstrating the intricate dance between philosophy, astronomy, and nascent scientific inquiry.

What remains constant is the human act of forming a hypothesis – a provisional explanation, a daring intellectual leap into the unknown. As our scientific tools become more sophisticated, our hypothesises become more precise, yet the fundamental philosophical questions about existence, purpose, and the nature of reality persist. The World's origin remains not just a scientific problem to be solved, but an eternal wellspring for philosophical wonder.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato Timaeus summary animated"

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Big Bang theory explained philosophically"