The Ethics of Slavery and Labor: A Philosophical Inquiry

The concepts of slavery and labor, while seemingly distinct in contemporary discourse, are profoundly intertwined in the history of human civilization and philosophical thought. This pillar page delves into the complex ethics surrounding human bondage and the nature of work, tracing how philosophers from antiquity to the modern era have grappled with questions of human ownership, the value of effort, and the fundamental principles of justice. From Aristotle's justifications for "natural slavery" to Marx's critique of alienated labor, we explore the moral arguments that have shaped our understanding of freedom, exploitation, and human dignity.

Defining the Core Concepts

To navigate this intricate subject, it's essential to establish a shared understanding of our key terms:

- Ethics: The branch of philosophy concerned with moral principles; what constitutes right and wrong conduct. In this context, we examine the moral permissibility of owning another human being and the justness of various labor arrangements.

- Slavery: A condition in which one human being is treated as property by another. This involves the denial of personal liberty, autonomy, and the right to one's own labor and body. Historically, it has encompassed chattel slavery, debt bondage, and various forms of forced servitude.

- Labor: Human effort, physical or mental, expended in the production of goods or services. Philosophically, labor is often considered a fundamental aspect of human existence, creativity, and self-realization, but it can also be a source of exploitation and alienation.

- Justice: The moral principle of fairness and equitable treatment. In the context of slavery and labor, justice demands examining whether social structures, economic systems, and individual actions uphold the inherent dignity and rights of all persons.

Historical and Philosophical Perspectives on Slavery

The institution of slavery has been a pervasive feature across diverse cultures and epochs, prompting centuries of ethical debate.

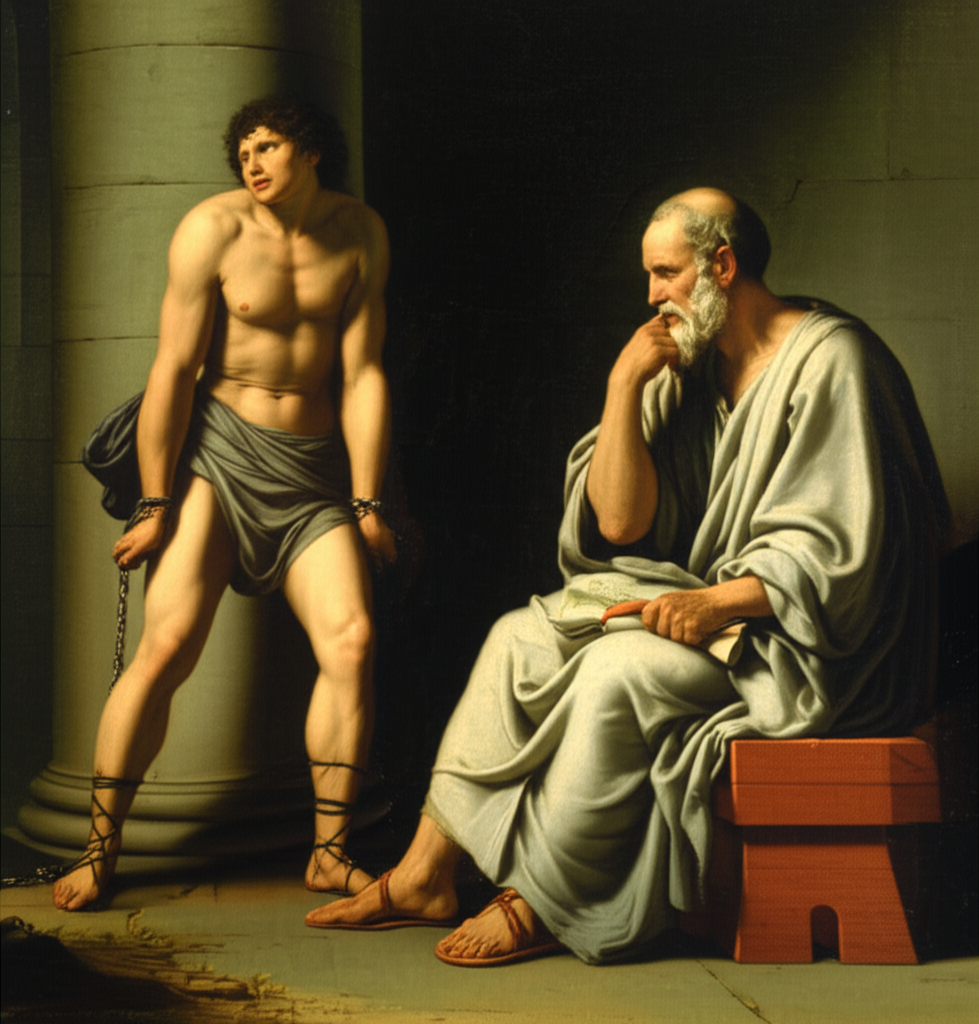

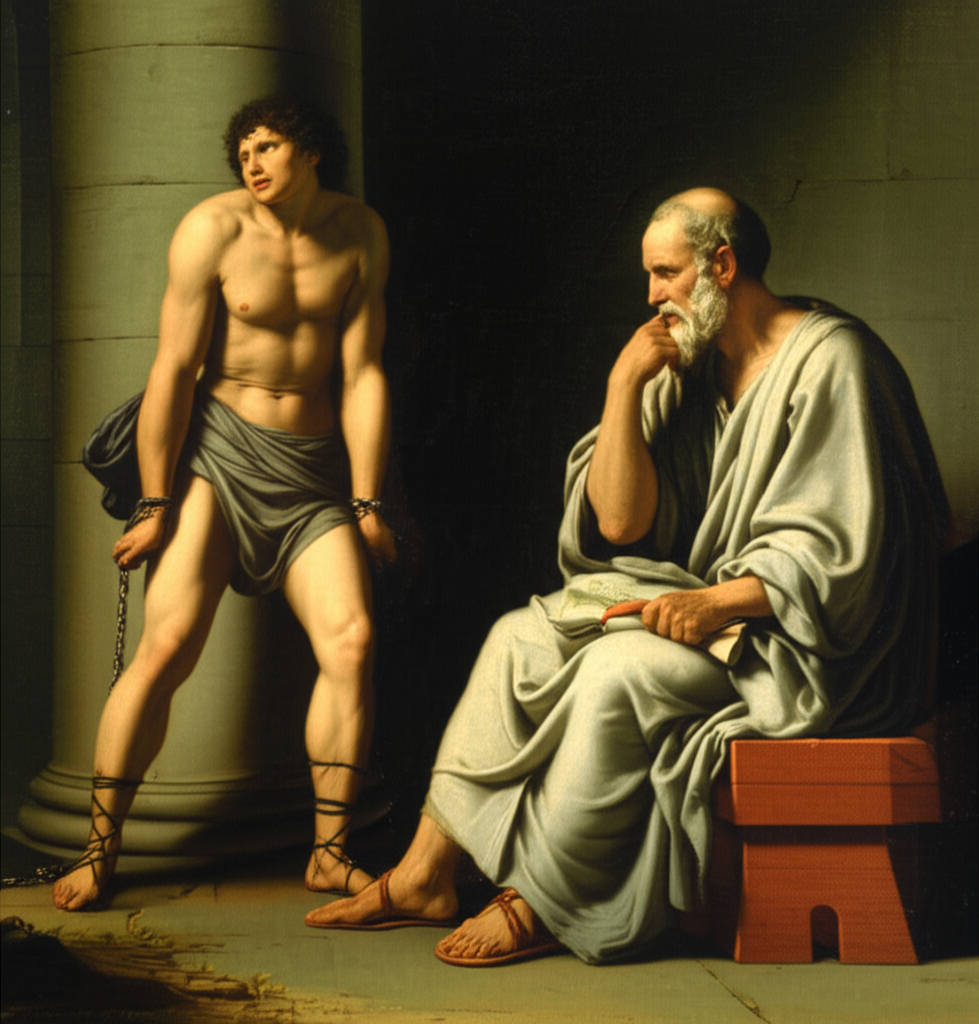

Ancient World: Justifications and Early Critiques

In ancient civilizations, slavery was often an accepted, even foundational, element of society.

- Aristotle (c. 384–322 BCE): In his Politics, Aristotle famously posited the concept of "natural slaves"—individuals who, by nature, lacked the capacity for rational self-governance and were thus better off being ruled by others. He argued that such individuals were "living tools," necessary for the leisure of citizens and the proper functioning of the household. This perspective, found within the Great Books of the Western World, provided a powerful, though deeply flawed, ethical justification for slavery that persisted for millennia.

- Plato (c. 428–348 BCE): While not explicitly theorizing on natural slavery to the same extent as Aristotle, Plato's ideal state in The Republic still implicitly relied on a hierarchical social structure where certain labor, often performed by non-citizens or those of lower status, supported the philosophical elite.

- The Stoics: In contrast, Stoic philosophers like Seneca emphasized an inner freedom that transcended external circumstances. They argued for the moral equality of all rational beings, suggesting that true slavery was a condition of the soul, not the body, thereby offering an early, albeit often abstract, critique of the institution.

Medieval Thought: Christian Perspectives

With the rise of Christianity, the ethical landscape shifted, though not always towards immediate abolition.

- Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE): In The City of God, Augustine viewed slavery not as natural, but as a consequence of sin—a punishment and a necessary evil in a fallen world. He did not advocate for its immediate abolition but emphasized the moral duties of masters and the spiritual equality of all before God. This nuanced position, also a cornerstone of the Great Books, allowed for the continued existence of slavery while subtly undermining its inherent justice.

- Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274 CE): Drawing on Aristotelian thought but tempered by Christian theology, Aquinas distinguished between natural law and positive law. He saw slavery as a convention of positive law, a result of human circumstances (like war or debt), rather than a dictate of natural law. While not condemning it outright, his framework opened avenues for questioning its moral basis.

The Enlightenment and the Rise of Abolitionism

The Enlightenment brought a radical re-evaluation of individual rights and human freedom, laying the groundwork for abolitionist movements.

- John Locke (1632–1704): In his Two Treatises of Government, Locke argued that every individual has a natural right to life, liberty, and property—including property in one's own person and labor. This concept fundamentally challenged the legitimacy of chattel slavery, asserting that no one could justly own another. His ideas were instrumental in shaping arguments for individual freedom and against absolute power.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778): Rousseau, in The Social Contract, declared that "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains." He saw slavery as a complete contradiction of human nature and the social contract, arguing that to surrender one's freedom was to surrender one's humanity.

- Immanuel Kant (1724–1804): Kant's categorical imperative, particularly the formulation to "act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never merely as a means to an end, but always at the same time as an end," provided a powerful ethical condemnation of slavery. Slavery inherently treats individuals as mere instruments for another's purposes, violating their intrinsic worth and autonomy.

The Philosophy of Labor: From Necessity to Alienation

Beyond outright slavery, the nature and ethics of labor have also been a central concern for philosophers, especially as societies industrialized.

Ancient and Early Modern Views of Labor

Historically, manual labor was often viewed as a lesser activity, sometimes associated with punishment or a lack of intellectual refinement.

- Ancient Greek and Roman Societies: Labor was often performed by slaves or the lower classes, allowing citizens the leisure for politics and philosophy. This contributed to a devaluation of physical work.

- John Locke: As mentioned, Locke saw labor as the source of property. When an individual mixes their labor with unowned resources, they make it their own. This concept was revolutionary, linking individual effort directly to rights and value.

- Adam Smith (1723–1790): In The Wealth of Nations, Smith analyzed the division of labor as a key driver of economic prosperity. While acknowledging its efficiency, he also noted its potential to dull the human mind through repetitive tasks, hinting at later critiques of industrial labor.

The Industrial Revolution and Marx's Critique of Alienated Labor

The dramatic societal shifts brought by the Industrial Revolution, with its factories and mass production, intensified ethical questions about labor.

- Karl Marx (1818–1883): Marx's Das Kapital (also part of the Great Books) offers a profound critique of labor under capitalism. He argued that while labor is the source of all value, the capitalist system alienates workers in four key ways:

- From the product of their labor: Workers do not own what they produce.

- From the act of labor: Work becomes a means to an end, rather than a fulfilling activity.

- From their species-being: Labor, which should be a creative and self-expressive act, becomes dehumanizing.

- From other human beings: Competition and class divisions separate workers from each other.

Marx's analysis highlights how even "free" labor can be exploitative, raising critical questions of justice in economic systems.

The Intertwined Nature of Slavery and Labor Exploitation

The philosophical journey through slavery and labor reveals a disturbing continuum of human exploitation. Arguments once used to justify chattel slavery—such as the supposed inferiority of certain groups or the economic necessity of forced labor—have often re-emerged in different forms to rationalize exploitative labor practices.

Modern forms of slavery, including human trafficking, debt bondage, and forced labor in global supply chains, demonstrate that the ethical challenges are far from resolved. These contemporary issues echo the ancient debates, forcing us to confront whether our economic systems truly uphold human dignity and justice. The struggle against slavery is not merely a historical footnote but an ongoing battle against all forms of human commodification and severe labor exploitation.

Seeking Justice in Labor and Freedom

The philosophical inquiry into slavery and labor ultimately leads to a profound demand for justice. This demand manifests in:

- Universal Human Rights: The recognition that all individuals possess inherent rights, including the right to freedom, personal autonomy, and fair treatment.

- Ethical Labor Practices: Advocating for fair wages, safe working conditions, the right to organize, and the elimination of child labor and forced labor.

- Economic Justice: Challenging systems that perpetuate vast inequalities and exploit vulnerable populations, ensuring that labor serves human flourishing rather than merely profit.

The ethics of slavery and labor compel us to remain vigilant against any system or ideology that diminishes human worth or denies fundamental freedoms. The lessons from the Great Books of the Western World remind us that the fight for justice is a continuous philosophical and practical endeavor.

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Philosophical perspectives on slavery and freedom" or "Karl Marx's theory of alienation explained""