The Unruly Heart: Navigating the Ethics of Desire

The human experience is inextricably linked to desire. From the simplest craving for sustenance to the most profound yearning for knowledge, love, or power, desire propels us, shapes our choices, and often dictates the very trajectory of our lives. But what happens when these powerful internal forces collide with the demands of morality? This article delves into the intricate philosophical landscape of The Ethics of Desire, exploring how various traditions within the Great Books of the Western World have grappled with the fundamental tension between what we want and what is right. We shall examine the nature of desire itself, its relationship to the will, and how its management (or mismanagement) leads us to ponder the very definitions of good and evil. Ultimately, understanding the ethics of desire is not merely an academic exercise but a critical journey into self-awareness and responsible living.

Ancient Echoes: Reason's Dominion Over Passion

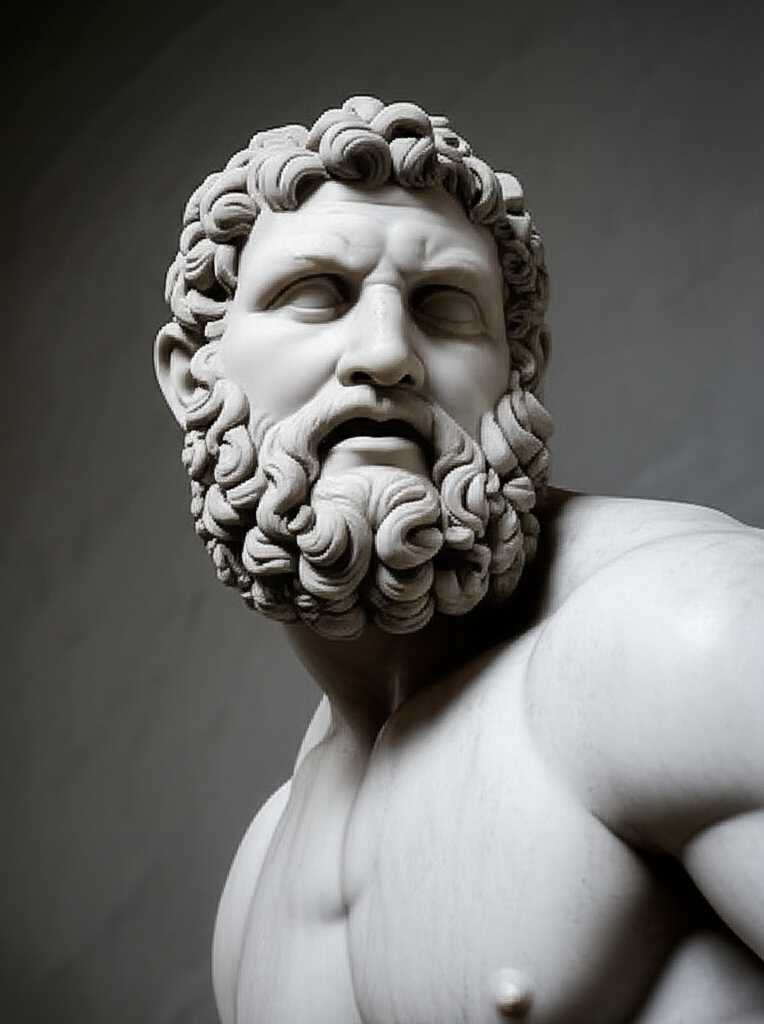

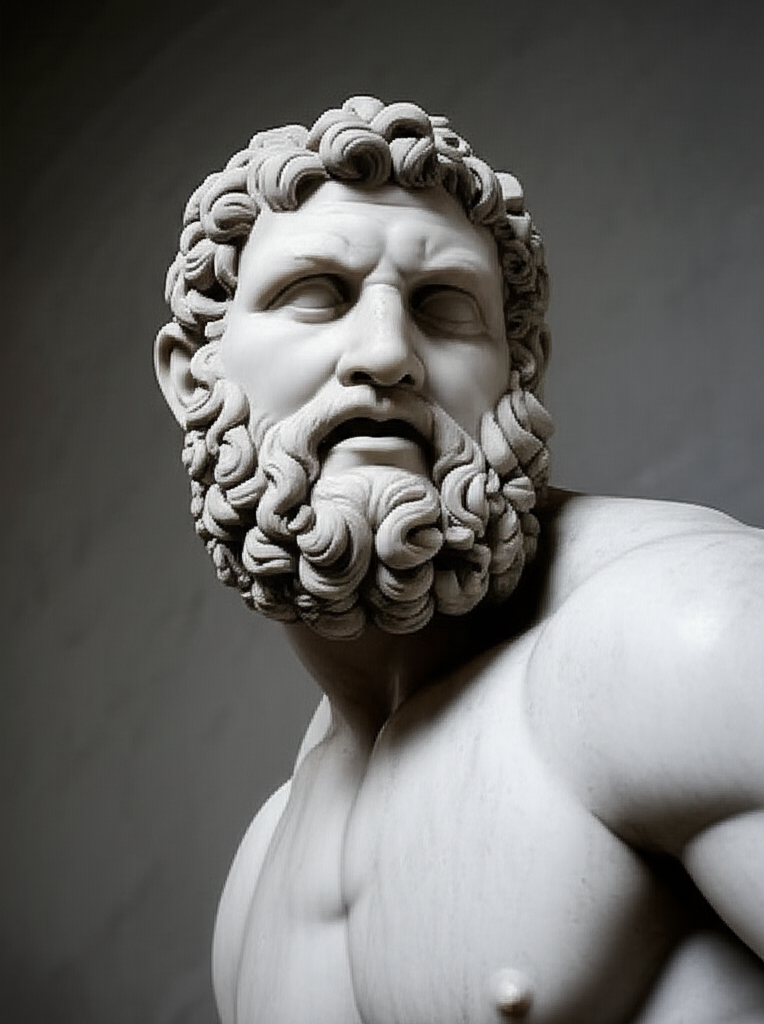

From the dawn of Western thought, philosophers have been acutely aware of the dual nature of desire. It is both a source of vitality and a potential harbinger of chaos.

- Plato's Tripartite Soul: In the Republic, Plato famously described the soul as having three parts: the rational, the spirited, and the appetitive. Desire, particularly the base, bodily appetites, resides in the appetitive part. For Plato, ethical living — indeed, a just society — depends on the rational part (reason) governing the spirited and appetitive parts. Unchecked desire leads to imbalance and injustice, both within the individual and the polis. The pursuit of the Good, the ultimate Form, requires transcending mere sensory desires.

- Aristotle's Virtuous Mean: Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, offered a more nuanced view. While acknowledging that excessive desires can lead to vice, he also recognized that desires themselves are not inherently evil. The key lies in their proper regulation through reason, aiming for the "golden mean." Courage, for instance, is the mean between rashness (excessive desire for glory/lack of fear) and cowardice (excessive desire for safety). For Aristotle, the will plays a crucial role in habituating ourselves to virtuous actions, thereby training our desires to align with the good.

The Christian Interlude: Sin, Salvation, and the Will

The advent of Christian thought introduced a profound shift in the discourse on desire, often imbuing it with a moral weight tied to sin and salvation.

- Augustine's Struggle: Saint Augustine, particularly in his Confessions, meticulously chronicles his personal battle with carnal desires. For Augustine, post-lapsarian humanity is afflicted by concupiscence – an inherent inclination towards sin, a disordered love that pulls the will away from God. This perspective casts desires, particularly those not directed towards divine love, as potentially leading to evil. The ethical imperative becomes one of redirecting the will through divine grace, transforming selfish desires into altruistic love. The struggle between the flesh and the spirit is a central theme, where the will is often seen as weak without divine intervention.

Modern Crossroads: Reason, Passion, and Good and Evil

The Enlightenment brought renewed scrutiny to the relationship between reason and passion, offering diverse perspectives on how desire should be ethically managed.

- Spinoza's Deterministic Passions: Baruch Spinoza, in his Ethics, presented a radical view. He argued that desires (or "affects") are not external forces but inherent modifications of our being, driven by our striving for self-preservation. Freedom, for Spinoza, is not about suppressing desire but understanding its causes through reason. By understanding why we desire what we desire, we can move from passive subjection to passions to active participation in our own nature, leading to a more rational and therefore more "good" life. The distinction between good and evil is often reframed as what enhances or diminishes our power of acting.

- Kant's Categorical Imperative: Immanuel Kant, in his Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, offers a stark contrast. For Kant, moral actions are not driven by desires or inclinations (which he considered heteronomous, or externally motivated) but by a pure, rational will acting out of duty. The Categorical Imperative demands that we act only according to maxims that we could universalize. Desires, while natural, are ethically neutral at best, and often a distraction from true moral action. An action is truly moral only if performed because it is the right thing to do, not because it satisfies a desire or inclination. The will to do good, irrespective of personal desire, is paramount.

Navigating the Ethical Landscape of Desire: Key Considerations

Understanding the ethics of desire requires us to consider several crucial questions that continue to challenge philosophers and individuals alike.

Table: Philosophical Approaches to Desire

| Philosopher/Tradition | View of Desire | Role of Will | Ethical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plato | Appetitive, often unruly; needs rational control | Reason's command over desires | Unchecked desire leads to individual/societal injustice |

| Aristotle | Natural, but requires regulation; aim for the mean | Habituation to virtue; training desires | Virtue is the harmonious integration of reason and desire |

| Augustine | Post-lapsarian concupiscence; prone to sin | Weakened by sin; requires divine grace for redirection | Disordered desire leads to sin and separation from God |

| Spinoza | Affects arising from self-preservation; natural | Understanding causes of desire leads to freedom | Rational understanding of desire leads to a "good" life |

| Kant | Heteronomous; not a basis for moral action | Pure, rational will acting from duty | Moral actions must transcend desire for universal good |

The Enduring Quest: Cultivating an Ethical Will

The journey through the ethics of desire reveals a consistent theme: the human struggle to align our inner promptings with our moral compass. Whether through Platonic reason, Aristotelian habituation, Augustinian grace, Spinozan understanding, or Kantian duty, the imperative to manage our desires for the sake of good and evil remains. The will stands as the crucial intermediary, either succumbing to raw impulse or asserting a higher, ethical direction.

This profound philosophical inquiry is not confined to ancient texts; it is a live question for each of us. How do we cultivate a will that directs our desires towards genuine good, rather than fleeting pleasure or destructive ambition? This introspection is the true heart of ethical living.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Ethics of Desire" - A deep dive into the Republic's view on appetite and reason."

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Kant and the Moral Will" - Exploring the categorical imperative and the role of duty over desire."