The Enduring Divide: Unpacking the Distinction Between Quality and Quantity

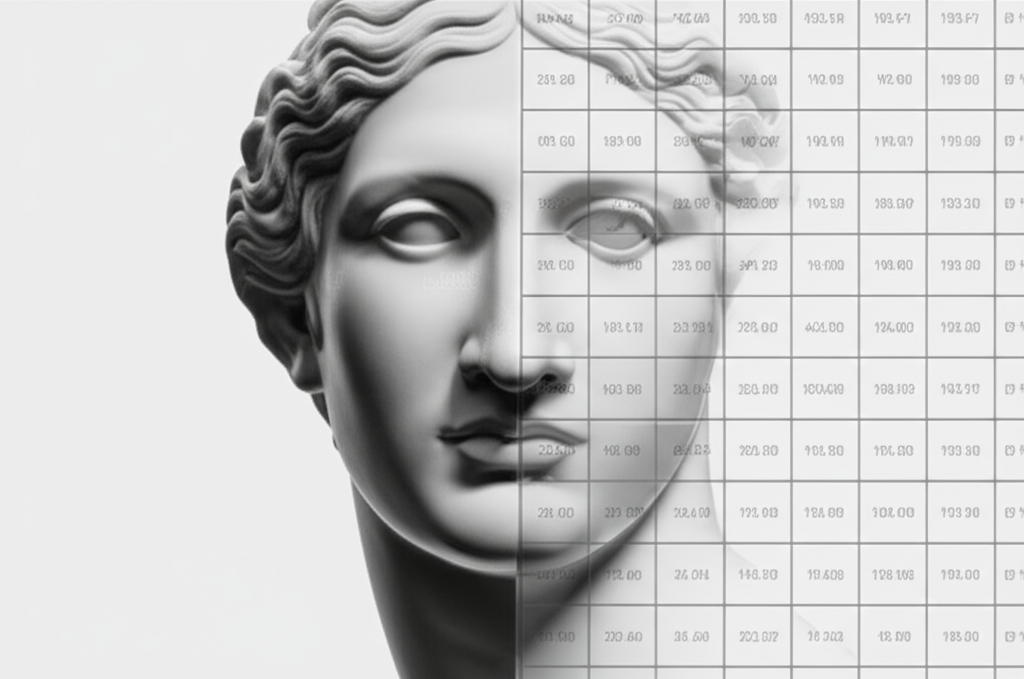

The fundamental division between quality and quantity is not merely an academic exercise; it is a bedrock concept that shapes our understanding of reality, from the grandest cosmic theories to the most intimate personal experiences. This article delves into this profound distinction, exploring its philosophical roots, its implications for scientific inquiry, and why it remains a vital lens through which we interpret the world. At its core, quantity refers to the measurable aspects of things—how much, how many, how big—while quality speaks to their intrinsic nature—what kind, what sort, how it feels. Grasping this difference is crucial for navigating both the objective world revealed by physics and the subjective realm of human experience.

Defining the Terms: What's the Difference?

Before we can explore the philosophical nuances, a clear definition of each term is essential. Though seemingly straightforward, their boundaries often blur in practical application, making the philosophical distinction all the more critical.

Quantity refers to the measurable attributes of an object or phenomenon. It deals with numerical values, magnitudes, and extents. If something can be counted, weighed, or dimensioned, it falls under the purview of quantity.

- Examples: Three apples, a mass of 5 kilograms, a temperature of 20 degrees Celsius, a duration of one hour.

Quality, on the other hand, describes the inherent characteristics, properties, or attributes that define the nature of something. It's about what something is, its essence, its "suchness." Qualities are often subjective or difficult to measure objectively.

- Examples: The redness of an apple, the sweetness of its taste, the warmth of the sun, the beauty of a sunset, the courage of a hero.

To illustrate, consider the following:

| Aspect | Quantity | Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | How much, how many, how big | What kind, what sort, its intrinsic nature |

| Measurement | Objective, numerical, scalable | Subjective, descriptive, inherent |

| Examples | Volume, weight, number, length, duration | Color, taste, texture, beauty, virtue |

| Inquiry | "How many stars are there?" | "What is the nature of a star?" |

A Historical Journey Through the Great Books

The distinction between quality and quantity is not new; it has been a cornerstone of Western thought since antiquity, deeply explored within the pages of the Great Books of the Western World.

- Aristotle, in his Categories, lists quantity and quality as two of the ten fundamental ways in which things can be said to exist (or be predicated). For Aristotle, a substance (like a man or a horse) has various accidents, among which are its qualities (e.g., "white," "grammatical") and its quantities (e.g., "two cubits long"). This foundational work provided a framework for understanding the basic constituents of reality.

- Later, during the Scientific Revolution, thinkers like René Descartes refined this distinction into what became known as primary and secondary qualities. Descartes, seeking certainty, argued that primary qualities (like extension, shape, motion, number) were objective and inherent in objects, capable of mathematical description—the very stuff of his new physics. Secondary qualities (like color, taste, sound, smell), however, were seen as subjective perceptions, effects produced in our minds by the primary qualities of objects.

- This line of thought was further developed by John Locke, who distinguished between qualities that are "utterly inseparable from the body" (primary) and those that are "nothing in the objects themselves but powers to produce various sensations in us" (secondary). George Berkeley famously challenged this, arguing that all qualities, primary or secondary, exist only as ideas in the mind, thus collapsing the distinction in a radical form of idealism.

These historical debates underscore the profound implications of how we categorize these aspects of reality, influencing everything from metaphysics to epistemology.

Quality and Quantity in Modern Physics

The rise of modern physics has largely been characterized by an extraordinary drive to reduce qualities to quantities. Where we once described heat as a quality of warmth, physics now quantifies it as the average kinetic energy of molecules. The quality of color is explained by the quantity of electromagnetic wavelength. Sound, once a sensory quality, becomes measurable pressure waves.

This reductionist approach has been incredibly successful, leading to unparalleled advancements in our understanding and manipulation of the natural world. By stripping away subjective qualities and focusing solely on measurable quantities, science has built predictive models of immense power.

However, this triumph of quantification raises deep philosophical questions:

- Is experience truly reducible? Can the quality of "redness" as a subjective experience be fully explained by a wavelength of light? Many philosophers argue that while the objective physical process can be quantified, the qualia—the raw, irreducible subjective experience—remains a qualitative phenomenon that resists purely quantitative description.

- The "Hard Problem" of Consciousness: This is particularly evident in the study of consciousness. While neuroscience can measure brain activity (quantities like neural firing rates, electrical potentials), it struggles to explain why these quantities give rise to subjective experiences (qualities like the feeling of pain or the taste of chocolate).

The Enduring Significance

Despite the scientific inclination to quantify the world, the distinction between quality and quantity remains profoundly significant. It reminds us that reality is multifaceted and that our descriptive tools, while powerful, may not capture its entirety.

- Human Experience: Our lives are rich with qualities: the love we feel, the beauty we perceive, the meaning we seek. These are not easily quantifiable, yet they are central to what it means to be human.

- Ethics and Aesthetics: Moral judgments and artistic appreciation are deeply qualitative. While we might quantify survey responses about happiness, the quality of happiness itself, or the quality of a just society, resists simple numerical evaluation.

- Holistic Understanding: A purely quantitative view risks overlooking the emergent properties and holistic qualities that arise from the interaction of many parts. A symphony is more than the sum of its individual notes; its quality emerges from their arrangement.

In conclusion, the distinction between quality and quantity is not merely an ancient philosophical relic but a living concept that continues to challenge and enrich our understanding. It forces us to confront the limits of measurement, the nature of subjective experience, and the multifaceted reality that lies beyond mere numbers.

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Primary and Secondary Qualities Philosophy" or "Qualia Philosophy Explained""