Unraveling the Fabric of Reality: The Philosophical Distinction Between Quality and Relation

In the vast landscape of philosophical inquiry, few distinctions are as fundamental, yet often overlooked, as that between quality and relation. These aren't merely academic terms; they are the very bedrock upon which we construct our understanding of the world, influencing everything from the way we describe an object to how we comprehend complex systems of thought. Grasping this core difference is essential for anyone seeking to sharpen their logic, refine their definition of concepts, and truly appreciate the nuanced architecture of reality. This pillar page will guide you through the intricate philosophical terrain, drawing insights from the enduring wisdom found within the Great Books of the Western World, to illuminate why this distinction is not just interesting, but absolutely indispensable.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Building Blocks of Being

- Defining Quality: What a Thing Is in Itself

- Defining Relation: The Ties That Bind Things Together

- The Logical Divide: Why the Distinction Matters for Thought

- Historical Echoes: Insights from the Great Books

- Practical Applications: Beyond Abstract Philosophy

- Conclusion: A Sharper Lens for Reality

1. Introduction: The Building Blocks of Being

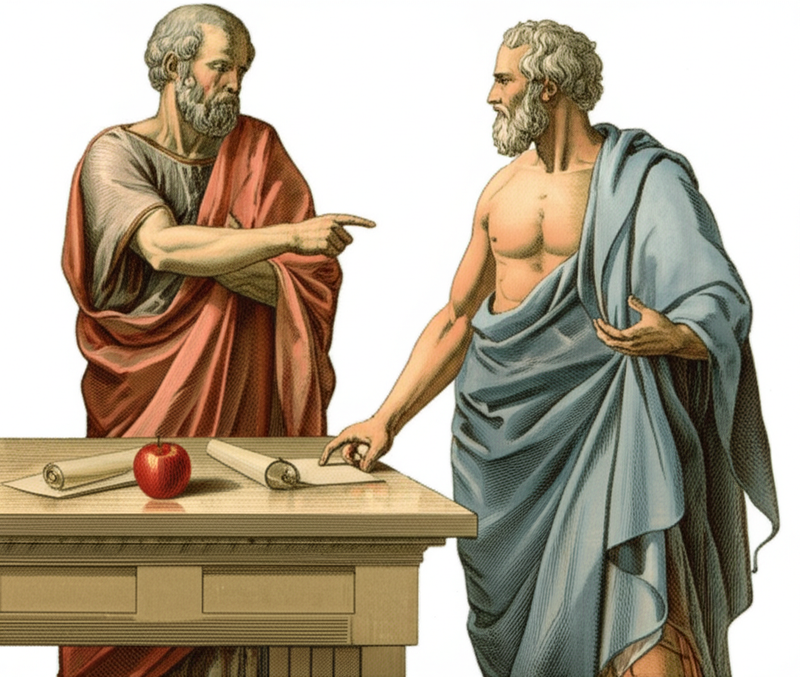

Imagine trying to describe an apple. You might say it's red, sweet, round, and crisp. These are its qualities. But then you might also say it's on the table, next to the knife, tastier than the pear, or from the orchard. These describe its relations to other things. While seemingly straightforward, the philosophical implications of these two categories are profound.

From the earliest attempts to categorize existence, thinkers have wrestled with how to classify what things are versus how they stand to other things. This distinction, particularly articulated by Aristotle in his Categories, provides a powerful framework for logic and metaphysics. Without a clear understanding, our arguments can become muddled, our definitions imprecise, and our grasp of reality incomplete. This exploration aims to provide that clarity, revealing how recognizing the difference between quality and relation empowers us to think more critically and articulate more accurately.

2. Defining Quality: What a Thing Is in Itself

When we speak of quality, we are referring to an inherent characteristic or attribute of a thing. It describes what kind of thing it is, or how it is, independent of its connection to other things. A quality inheres in a subject.

The Essence of Quality

- Inherence: A quality exists in a substance. The "redness" exists in the apple; the "wisdom" exists in the philosopher.

- Independence for Definition: The definition of "red" doesn't inherently require reference to anything else. It's a color, a specific wavelength of light, or a sensory experience. Similarly, "wise" describes a characteristic of an individual mind, not their connection to another mind.

- Categories of Quality: Aristotle identified four types of quality:

- Habits or Dispositions: Knowledge, virtue, health (e.g., being learned, being healthy).

- Capacities or Incapacities: Ability to run, inability to see (e.g., being strong, being blind).

- Affective Qualities or Affections: Sweetness, redness, hotness (e.g., being sweet, being hot).

- Figure and the Shape of a Thing: Roundness, straightness (e.g., being spherical, being triangular).

Consider the following examples to solidify your understanding of quality:

| Example of Quality | Description |

|---|---|

| Redness | An inherent color of an object. |

| Wisdom | An intrinsic intellectual virtue of a person. |

| Hardness | A property describing a material's resistance. |

| Tallness | A measurement of height, a characteristic of form. |

| Sweetness | A taste, an inherent sensory property. |

These qualities describe a thing's internal state or nature, its "whatness," rather than how it stands in comparison or connection to something external.

3. Defining Relation: The Ties That Bind Things Together

In stark contrast to quality, a relation describes how one thing stands in reference or connection to another. It is not an inherent property of a single object, but rather a bridge or link between two or more objects.

The Interconnectedness of Relation

- Dependence on Multiple Subjects: A relation cannot exist in isolation. Something is "larger than something else," "a parent of a child," or "similar to another object." The definition of a relation inherently requires reference to at least two terms.

- Reciprocity (Often, but not always): If A is the father of B, then B is the child of A. However, "A is to the right of B" doesn't mean B is to the right of A.

- Not an Intrinsic Attribute: Being "to the right of" is not a property of the object itself, but of its position relative to another object. If the other object moves, the relation changes, but the first object's inherent qualities (like its color or material) remain the same.

Let's look at some illustrative examples of relation:

| Example of Relation | Description |

|---|---|

| Larger than | A comparative measure between two or more objects. |

| Father of | A familial connection between two individuals. |

| Similar to | A resemblance or shared characteristic between distinct entities. |

| To the right of | A spatial arrangement between objects. |

| Cause of | A causal link between an action or event and its consequence. |

These examples highlight that relations are always about "betweenness" – how things are positioned, compared, or connected in the grand scheme of existence.

and its position 'on the table' or its comparison 'to the scroll' (relation). Their expressions are thoughtful, conveying the intellectual rigor of philosophical categorization.)

and its position 'on the table' or its comparison 'to the scroll' (relation). Their expressions are thoughtful, conveying the intellectual rigor of philosophical categorization.)

4. The Logical Divide: Why the Distinction Matters for Thought

The philosophical distinction between quality and relation is not merely an exercise in categorization; it profoundly impacts our logic, our language, and our capacity for clear reasoning. When we confuse a quality with a relation, or vice-versa, we risk making fundamental errors in our understanding of propositions and arguments.

Predicates and Propositions

In logic, predicates are typically used to describe subjects.

- Quality as a Predicate: When we say "Socrates is wise," "wise" is a predicate expressing a quality of Socrates. Its truth value depends solely on Socrates' inherent characteristics.

- Relation as a Predicate: When we say "Socrates is taller than Plato," "taller than Plato" is a predicate expressing a relation. Its truth value depends on both Socrates and Plato, and their comparative heights.

This distinction is crucial for understanding the structure of propositions and for avoiding fallacies. For instance, attributing a relational property as if it were an intrinsic quality can lead to mistaken conclusions. Just because something is "to the left of" something else doesn't make "leftness" an inherent quality of the object.

Implications for Definition and Understanding

The ability to accurately define concepts relies heavily on distinguishing between qualities and relations.

- Defining by Quality: When defining a "chair," we might list its qualities: "a piece of furniture," "with a back," "for sitting." These are inherent to the chair itself.

- Defining by Relation: Defining "parent" necessarily involves a relation: "one who has begotten or borne a child." The relation is integral to the definition.

Confusing these can lead to circular definitions or definitions that fail to capture the true essence of the concept. For example, defining "tall" merely as "taller than most" is a relational definition, which works, but the underlying concept of "tallness" as a quality (a measure of height) is also present. The logic of how we construct our definitions is thus deeply intertwined with this philosophical distinction.

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle's Categories Explained" or "Understanding Predicates in Logic""

5. Historical Echoes: Insights from the Great Books

The profound significance of quality and relation resonates throughout the Great Books of the Western World, primarily stemming from Aristotle's groundbreaking work.

Aristotle's Categories: The Foundation

In his treatise Categories, Aristotle laid out ten fundamental ways in which being can be predicated of a subject. Among these, Quality (Poion) and Relation (Pros Ti) stand as two distinct and vital categories.

- Aristotle on Quality: He defines quality as that by which things are said to be such and such. It answers the question "What kind?" It's an internal attribute.

- Aristotle on Relation: He defines relations as things which are said to be just what they are, of other things or in some other way in reference to other things. It answers the question "How does it stand to something else?"

This systematic approach provided a logic for understanding the different modes of existence and predication, profoundly influencing Western thought for centuries.

Beyond Aristotle: Kant and Modern Philosophy

While Aristotle provided the initial framework, later philosophers, though not always explicitly using the same terminology, grappled with similar distinctions.

- Immanuel Kant's Categories: In his Critique of Pure Reason, Kant also proposed categories of understanding, which, while different from Aristotle's, still reflect an attempt to structure how we comprehend reality. His categories of Quality (Reality, Negation, Limitation) and Relation (Inherence and Subsistence, Causality and Dependence, Community) show a continuing philosophical effort to distinguish between intrinsic properties and connections. Kant's emphasis on the mind's role in structuring experience further highlights the importance of these conceptual tools.

- Locke's Simple and Complex Ideas: John Locke, in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, distinguished between simple ideas (like "red" or "cold") which might be seen as foundational qualities, and complex ideas, many of which involve relations (like "father" or "cause").

The enduring presence of these concepts, even under different names, across diverse philosophical traditions underscores their fundamental importance in understanding how we perceive, categorize, and articulate the world.

6. Practical Applications: Beyond Abstract Philosophy

Understanding the difference between quality and relation isn't just for philosophers in ivory towers. It's a practical skill that enhances critical thinking, communication, and problem-solving in everyday life.

Sharpening Argumentation and Avoiding Fallacies

- Precise Language: By distinguishing between qualities and relations, we can articulate our arguments with greater precision. For example, instead of saying "This policy is bad," which is a qualitative judgment (and subjective), one might say "This policy is detrimental to economic growth," which highlights a specific relation and allows for more objective evaluation.

- Identifying Misleading Statements: Many rhetorical tricks and fallacies rely on confusing these categories. For instance, attributing a relational property (e.g., "being a competitor") as an inherent quality (e.g., "being inherently hostile") can demonize an opponent unfairly.

- Analytical Thinking: In science, law, and even personal relationships, accurately identifying whether a characteristic is intrinsic or relational helps in isolating variables, understanding causality, and making sound judgments. For example, a doctor diagnosing a patient needs to distinguish between intrinsic symptoms (qualities) and how those symptoms relate to other conditions or external factors.

Enhanced Communication and Definition

- Clearer Explanations: When explaining complex concepts, being able to articulate what something is (its qualities) versus how it interacts or connects (its relations) leads to far more comprehensible and robust definitions.

- Avoiding Ambiguity: Much ambiguity in language stems from a blurring of these lines. Asking "Is this an inherent property or is it dependent on something else?" can often clarify misunderstandings.

By consciously applying this distinction, we move beyond superficial descriptions to a deeper, more structured comprehension of the phenomena around us, fostering a more rigorous and intellectually honest approach to both thought and communication.

7. Conclusion: A Sharper Lens for Reality

The philosophical distinction between quality and relation, though originating in the ancient world, remains profoundly relevant today. It is a powerful lens through which we can scrutinize the very fabric of reality, allowing us to differentiate between what a thing is in itself and how it stands in reference to everything else.

From the foundational logic of Aristotle to the categorical frameworks of Kant, the Great Books of the Western World consistently underscore the importance of this distinction for robust thought. By internalizing the difference between an intrinsic quality and an external relation, we not only enhance our capacity for precise definition and clear argumentation but also gain a more nuanced and accurate understanding of the interconnected world we inhabit. Embrace this distinction, and you will find your intellectual toolkit significantly expanded, ready to tackle the complexities of philosophy and life with newfound clarity.