The Philosophical Divide: Distinguishing Monarchy from Tyranny

The terms monarchy and tyranny often appear in discussions about government, frequently conflated or misunderstood. However, a deep dive into classical philosophy, particularly the works found within the Great Books of the Western World, reveals a crucial and enduring distinction. At its core, the difference lies not merely in the number of rulers, but in their purpose and legitimacy. A monarchy is traditionally defined as the rule of one for the common good, acting in the best interests of the entire populace. In stark contrast, tyranny represents the corrupt perversion of this form, where a single ruler governs solely for their own self-interest, often through oppressive means and without regard for justice or the welfare of their subjects. Understanding this fundamental philosophical divergence is essential for comprehending the dynamics of political power, then and now.

Unpacking the Definitions: Monarchy and Tyranny in Classical Thought

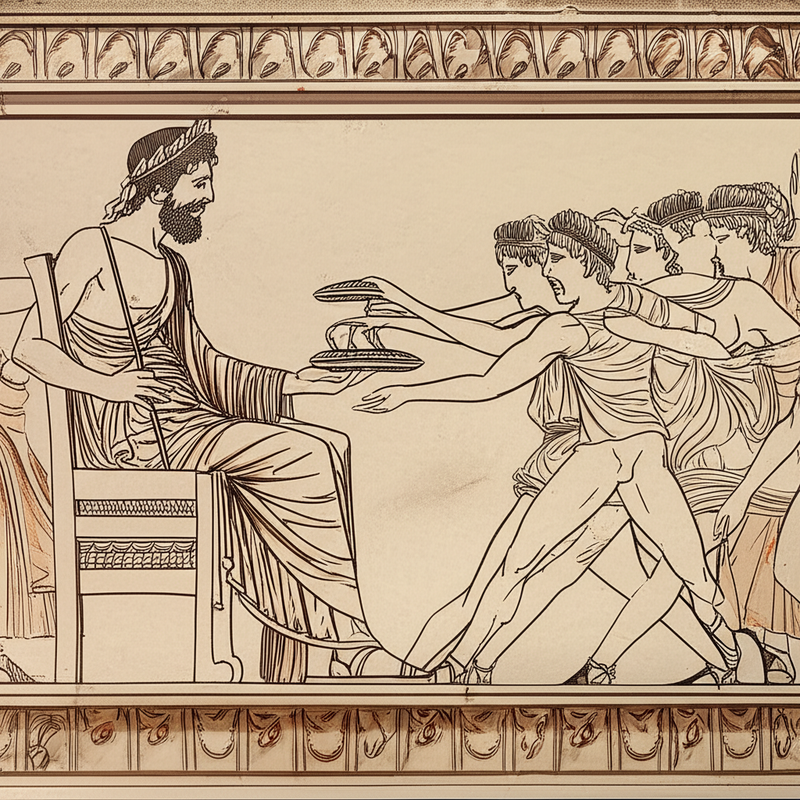

To truly grasp the chasm between these two forms of single-person rule, we must turn to the venerable texts that first articulated these concepts with such precision. Philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, whose insights form the bedrock of Western political thought, meticulously defined and contrasted these governmental structures.

The Ideal of Monarchy: Rule for the Common Good

The classical definition of monarchy describes a form of government where sovereignty resides in a single individual, the monarch, who exercises power with a primary commitment to the welfare and prosperity of the entire community. This ruler is often seen as embodying the state, acting as a benevolent guardian.

- Aristotle's Perspective: In his Politics, Aristotle classifies monarchy as one of the "right" forms of government, alongside aristocracy and polity. He posits that a true monarch rules "with a view to the common interest," governing according to law and custom, and often inheriting their position through established lineage. The monarch's legitimacy stems from their perceived wisdom, virtue, and dedication to justice. They are a steward, not an owner, of the state.

- Plato's Republic: While Plato often favors an aristocracy of philosopher-kings, his discussions of ideal rule still point to a single, virtuous leader as a potentially excellent form of governance, provided that leader is guided by reason and the pursuit of the Good.

A key characteristic of monarchy, therefore, is its inherent legitimacy—derived from tradition, divine right, or a social contract—and its orientation towards the collective good.

The Perversion of Power: The Rise of Tyranny

Tyranny, on the other hand, is universally condemned by classical thinkers as the most debased and dangerous form of government. It is the corrupted shadow of monarchy, emerging when the ruler abandons their duty to the people and instead pursues purely personal gain, ambition, or pleasure.

- Aristotle's Critique: For Aristotle, tyranny is the "deviation" of monarchy. A tyrant rules "with a view to the interest of the ruler only," relying on force, fear, and oppression rather than law or consent. They dismantle legal frameworks, suppress dissent, and impoverish their subjects to maintain their lavish lifestyle and power. The tyrant holds power illegitimately, often seizing it through violence or deception, and maintains it through coercion.

- Plato's Warning: In The Republic, Plato vividly describes the tyrannical man as consumed by insatiable desires, particularly the "erotic love of the tyrant." This individual, once a protector, becomes a slave to their own passions, imposing their will on the state, executing rivals, and fostering perpetual war to distract and control the populace. The tyrannical state is one of extreme injustice, where freedom is crushed, and the ruler lives in constant paranoia.

The hallmark of tyranny is its illegitimacy and its profound selfishness.

Key Distinctions: Monarchy vs. Tyranny

To clarify the philosophical divide, let's delineate the core differences between these two forms of single-person rule:

| Feature | Monarchy | Tyranny |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose of Rule | For the common good, welfare of the citizens | For the self-interest, pleasure, and power of the ruler |

| Basis of Power | Law, custom, tradition, divine right, consent | Force, fear, fraud, suppression |

| Legitimacy | Legitimate (seen as rightful and just) | Illegitimate (seized and maintained unjustly) |

| Relationship to Law | Rules according to established laws and customs | Rules above or against the law, arbitrary rule |

| Treatment of Subjects | Protects, provides justice, fosters well-being | Oppresses, exploits, instills fear, denies freedom |

| Stability | Generally stable due to legitimacy and support | Inherently unstable due to popular resentment and internal strife |

| Virtue | Associated with wisdom, justice, prudence | Associated with greed, cruelty, paranoia, injustice |

The Philosophical Weight of the Distinction

Why did these ancient philosophers invest so much energy in drawing this line? Because the distinction between a true monarch and a tyrant is not merely academic; it speaks to the very essence of justice, political legitimacy, and the purpose of government.

- Justice: A monarchical rule, at its best, is meant to embody justice, ensuring fairness and upholding the rights of the citizens. Tyranny, conversely, is the antithesis of justice, where arbitrary power trumps all ethical considerations.

- Legitimacy: The concept of legitimacy is crucial for any stable political order. A monarch's rule is accepted because it is perceived as right and proper. A tyrant's rule, lacking this moral foundation, is inherently precarious, relying on coercion rather than consent.

- The Common Good: The idea that government should serve the common good is a recurring theme in classical philosophy. Monarchy, in its ideal form, is a realization of this principle, whereas tyranny is its stark rejection.

Modern Echoes and Enduring Relevance

While the specific forms of government have evolved dramatically since antiquity, the philosophical distinction between rule for the common good and rule for self-interest remains profoundly relevant. We may no longer have hereditary monarchs in many nations, but the spirit of monarchy (benevolent leadership, rule of law) and the spirit of tyranny (authoritarianism, oppression, personal enrichment at public expense) persist in various political systems.

Contemporary discussions about leadership, accountability, and human rights are, in many ways, an ongoing dialogue with these ancient definitions. When we critique corrupt leaders, question abuses of power, or advocate for transparent government, we are, consciously or unconsciously, invoking the very criteria that Aristotle and Plato used to differentiate a just ruler from a tyrant. The enduring value of these classical texts is their ability to provide a timeless framework for evaluating political authority and moral governance.

Conclusion: A Timeless Criterion for Governance

The difference between monarchy and tyranny is not a subtle nuance but a foundational philosophical chasm. It is the distinction between a ruler who serves the state and one who enslaves it; between governance by law and governance by whim; between the pursuit of the common good and the indulgence of selfish desires. The Great Books of the Western World teach us that the form of government is less important than its purpose and the character of its ruler. This ancient wisdom provides an invaluable lens through which to scrutinize power, demand accountability, and strive for just societies in any era.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Aristotle Politics forms of government explained"

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato Republic allegory of the cave political philosophy"