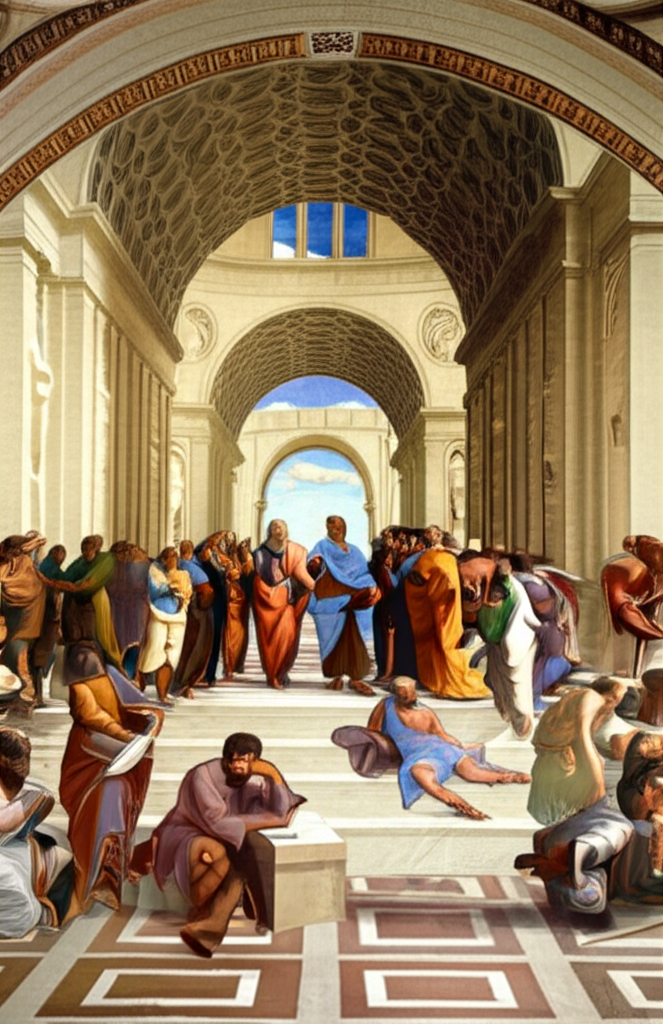

The Enduring Enigma: Exploring the Concept of the Soul in Ancient Philosophy

The concept of the soul stands as one of the most persistent and profound inquiries within the annals of philosophy. From the earliest musings of pre-Socratic thinkers to the towering systems of Plato and Aristotle, ancient philosophers grappled with its nature, purpose, and ultimate destiny. This pillar page delves into the multifaceted interpretations of the soul across various ancient schools of thought, examining how these foundational ideas shaped the very landscape of metaphysics and our understanding of being. We will explore its perceived substance, its relationship to the body, its role in cognition and ethics, and its implications for human existence, drawing from the rich tapestry of the Great Books of the Western World.

What is the Soul? Early Inquiries and Pre-Socratic Speculations

Before the systematic inquiries of classical Greek philosophy, the idea of the soul (ψυχή, psyche) was often intertwined with life force, breath, or a ghostly essence that departed the body at death. Homeric epics, for instance, depict the psyche as a shadowy image, a mere shade in the underworld, distinct from the vibrant, living person.

The pre-Socratic philosophers, driven by a quest for the fundamental principles of the cosmos, began to move beyond mythical explanations.

Early Materialist and Vitalist Views

- Thales: Believed that "all things are full of gods," and magnetic stones possess a psyche because they can move iron. This suggests a vitalistic principle inherent in matter.

- Anaximenes: Proposed air as the fundamental substance, equating the soul with air that gives life and holds the body together, much like air encompasses the world.

- Heraclitus: Saw the soul as composed of fire, a dynamic and ever-changing element. A dry soul was considered the wisest, suggesting a link between the soul's purity and rational thought.

- Democritus: A leading atomist, conceived of the soul as composed of fine, smooth, spherical atoms, much like fire atoms, distributed throughout the body. For Democritus, the soul was purely material, and its actions were reducible to the motion of these atoms.

These early thinkers, while diverse, laid the groundwork for later debates, particularly concerning the soul's materiality versus its immateriality, and its connection to the very essence of being.

Socrates and Plato: The Immortal, Rational Soul

The Socratic revolution shifted philosophical focus from the cosmos to the human being, and with it, the soul took center stage. Socrates, as interpreted by Plato, was less concerned with the soul's physical composition and more with its ethical and intellectual well-being.

The Socratic Imperative: Care of the Soul

Socrates famously asserted that the unexamined life is not worth living, implying that the primary duty of human beings is to care for their soul. For him, the soul was the seat of intelligence and character, the true self, distinct from the physical body. Virtue (ἀρετή, aretē) was knowledge, and vice was ignorance, directly impacting the health of the soul.

Plato's Dualism: Soul, Body, and the Forms

Plato developed Socrates' ideas into a comprehensive system of metaphysics and epistemology, where the soul plays a pivotal role.

Key Platonic Concepts of the Soul:

-

Immortality: In dialogues like the Phaedo, Plato argues vehemently for the soul's immortality. He presents several arguments, including the Argument from Recollection (souls must have existed prior to birth to "recollect" eternal truths), the Argument from Opposites (life comes from death, implying a cycle), and the Argument from Simplicity (the soul, being non-composite, cannot be broken down and thus cannot perish).

-

Pre-existence and Transmigration: Plato believed the soul existed before its embodiment, inhabiting the realm of the Forms, where it gained true knowledge. Upon entering a body, it "forgets" this knowledge, which can then be recollected through philosophical inquiry. He also posited transmigration (reincarnation) based on the soul's moral choices in life.

-

Tripartite Soul: In the Republic, Plato describes the soul as having three distinct parts, often in conflict:

- Rational (λογιστικόν, logistikon): The highest part, associated with reason, wisdom, and the pursuit of truth. Its virtue is wisdom.

- Spirited (θυμοειδές, thumoeides): Associated with emotions like anger, courage, and honor. Its virtue is courage. It acts as an ally to reason.

- Appetitive (ἐπιθυμητικόν, epithumētikon): Associated with bodily desires and appetites (food, drink, sex). Its virtue is temperance.

Plato argued that a just and harmonious individual is one where the rational part governs the spirited and appetitive parts, leading to an ordered being. This hierarchy reflects his broader metaphysics, where the rational soul is akin to the eternal Forms, while the body is transient and mutable.

Aristotle: The Soul as the Form of the Body

Aristotle, Plato's most famous student, offered a profoundly different, yet equally influential, account of the soul. Rejecting Plato's sharp dualism and separate realm of Forms, Aristotle embraced a more empirical and biological approach.

Hylomorphism: Soul and Body as an Inseparable Unity

For Aristotle, the soul (ψυχή, psyche) is not a separate entity imprisoned in the body but rather the form (εἶδος, eidos) of a natural, organized body potentially possessing life. This is his doctrine of hylomorphism – every substance is a composite of matter (ὕλη, hyle) and form.

Key Aristotelian Concepts of the Soul:

-

The Soul as First Actuality: In De Anima (On the Soul), Aristotle defines the soul as "the first actuality of a natural body having life potentially." It is what makes a living body alive; it is the animating principle. Without the body, the soul cannot exist, just as the form of a statue cannot exist without the bronze.

-

Three Types of Souls: Aristotle categorized souls based on their capacities, forming a nested hierarchy:

- Nutritive Soul (Vegetative): Possessed by plants, animals, and humans. Responsible for basic life functions: growth, nutrition, reproduction.

- Sentient Soul (Animal): Possessed by animals and humans. Includes the capacities of the nutritive soul, plus sensation (perception), desire, and locomotion.

- Rational Soul (Human): Possessed only by humans. Includes the capacities of the nutritive and sentient souls, plus thought, reason, and deliberation. This capacity for abstract thought is what distinguishes human being.

Aristotle's conception emphasizes that the soul's functions are inextricably linked to bodily organs. For instance, sight is a function of the eye, not merely the soul.

-

Immortality (Ambiguous): Unlike Plato, Aristotle was less clear about the soul's immortality. While he believed the active intellect (νοῦς ποιητικός, nous poietikos) might be separate and immortal, this aspect is one of the most debated and obscure parts of his philosophy. The individual, composite soul (matter and form) perishes with the body.

Aristotle's approach grounded the study of the soul within the natural world, influencing centuries of biological and psychological thought, and shaping the discourse on the nature of being as a composite entity.

Post-Aristotelian and Hellenistic Interpretations

Following the classical period, Hellenistic schools continued to grapple with the soul, often in the context of ethics and human flourishing.

Stoicism: The Soul as Pneuma

The Stoics, emphasizing rationality and living in harmony with nature, viewed the soul as a material substance: a fragment of the divine fiery pneuma (breath/spirit) that pervades the cosmos.

- Material and Mortal: The Stoic soul was corporeal, though composed of a very fine, ethereal substance. It was generally considered mortal, dissolving back into the cosmic pneuma after death, though some Stoics believed it might persist for a time.

- Eight Parts: The soul was typically divided into eight parts, with the ruling part (hegemonikon) located in the heart, responsible for reason, judgment, and impulses. Control over one's hegemonikon was paramount for achieving virtue and tranquility.

Epicureanism: The Soul as Atoms

Epicurus, a materialist, followed Democritus in positing that the soul was composed of fine, smooth atoms, distributed throughout the body.

- Material and Mortal: For Epicurus, the soul was entirely material and dispersed upon death, meaning there was no afterlife, and thus no reason to fear death. This view was central to his ethical system, which sought to eliminate fear and anxiety.

- Sensation and Thought: Sensation and thought were explained by the movement and interaction of these soul atoms.

Neoplatonism: The Soul's Ascent to the One

Plotinus, the founder of Neoplatonism, revitalized Plato's metaphysics with a mystical dimension. For Plotinus, the soul was an emanation from the divine, transcendent "One."

- Hierarchical Emanation: The cosmos emanates from the One, through Nous (Intellect), to the World-Soul, and then to individual souls.

- Descent and Ascent: Individual souls "descend" into bodies, a process seen as a fall from their divine origin. The goal of human life is to purify the soul through asceticism, contemplation, and philosophical inquiry, allowing it to ascend back to the Nous and ultimately to the One. This involved a deep spiritual journey and a profound understanding of one's true being as connected to the divine.

Enduring Questions and Legacy

The ancient philosophical inquiries into the soul laid the foundation for much of Western thought. The debates they initiated continue to resonate in contemporary discussions about consciousness, identity, artificial intelligence, and the nature of human being.

Key Debates that Persist:

- Material vs. Immaterial: Is the soul a physical entity or a non-physical substance?

- Mortal vs. Immortal: Does the soul perish with the body or continue to exist?

- Unified vs. Composite: Is the soul a single, indivisible entity, or does it have distinct parts or faculties?

- Relationship to the Body: Is the soul distinct from the body, or is it inextricably linked as its form or animating principle?

- Source of Identity: What aspects of the soul (reason, memory, character) constitute personal identity?

These questions are not merely academic; they profoundly influence our ethical frameworks, our understanding of life and death, and our place in the cosmos. The ancient philosophers, through their rigorous exploration of the soul, provided a rich vocabulary and a set of enduring problems that continue to challenge and inspire philosophical inquiry into metaphysics and the very essence of being.

Conclusion

The journey through ancient philosophy reveals the concept of the soul as a dynamic and central theme, evolving from primitive notions of life force to sophisticated theories of consciousness, ethics, and metaphysics. From Plato's immortal, tripartite soul guiding us towards the Forms, to Aristotle's soul as the animating form of the body, and the diverse materialist and spiritual interpretations of the Hellenistic schools, these thinkers grappled with fundamental questions about human nature and our place in the universe. Their insights not only shaped the trajectory of Western thought but continue to offer profound perspectives on what it means to possess a soul and to truly be.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato's Theory of the Soul Explained"

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Aristotle De Anima Summary"