Our Daily Bread: Is It Alive or Dead?

Few would call a loaf of bread alive. Yet when it emerges from the oven, it feels animated — warm, fragrant, crackling, as if it’s breathing. For a brief window, it’s perfect. Hours later, it hardens, turns stale, and becomes little more than memory.

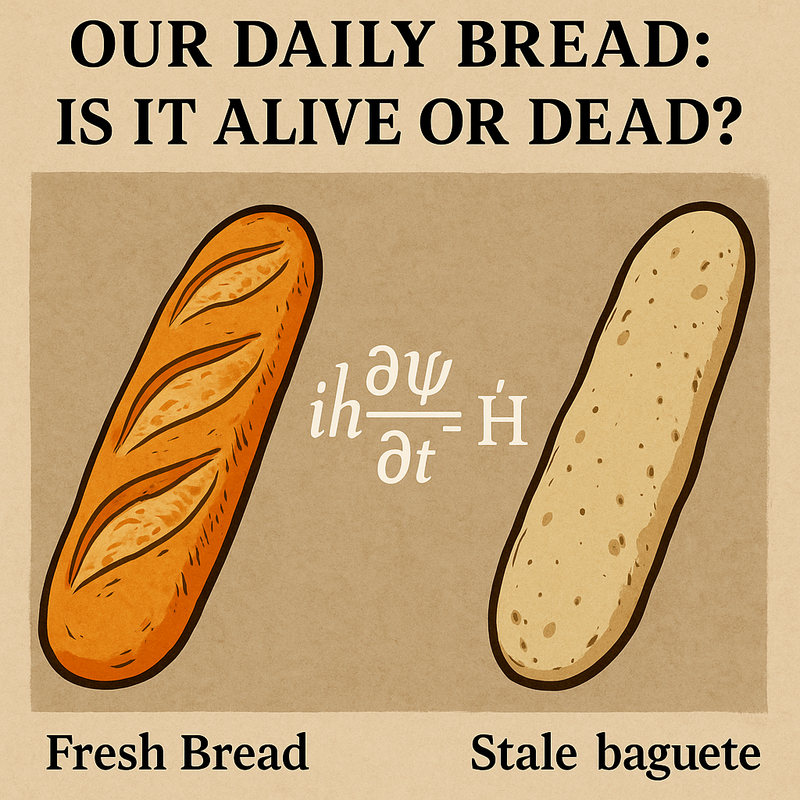

A fresh baguette is like a quantum state: for a moment, it exists in possibility. To one observer, it is “alive” — warm, edible, full of promise. To another, hours later, it is “dead” — stale, inedible, discarded. Like Schrödinger’s thought experiment, the bread hovers between states until observed, until tasted, until time collapses the probability.

But here’s the twist: two observers can disagree. One might delight in the baguette at its chewy midpoint, another might already call it ruined. Unlike Schrödinger’s cat — which must be either alive or dead — bread stretches the paradox. It teaches us that edibility itself is subjective, and the observer decides when the loaf has crossed over.

The baguette, then, becomes a quiet wave function. Its freshness decays, its possibilities collapse, and we are reminded that life — bread or human — is always on the edge of transformation. The lesson is simple: savor the loaf while it is still warm.