In the grand tapestry of human civilization, few debates have resonated with such enduring significance as the age-old question of how best to govern. From the philosopher-kings of ancient Greece to the modern republics of today, the fundamental choice between vesting power in one sovereign or distributing it among the many defines the very character of a State. This article delves into the core tenets, historical trajectories, and philosophical underpinnings of Monarchy and Democracy, exploring their respective strengths, weaknesses, and the perennial quest for a just and stable Government.

The Perennial Question of Governance: Monarchy vs. Democracy

The choice of Government is arguably the most critical decision a society faces, shaping everything from individual liberties to collective prosperity. For millennia, humanity has grappled with various structures of the State, but none have been theorized, implemented, and debated as intensely as Monarchy and Democracy. This exploration, drawing heavily from the Great Books of the Western World, seeks to illuminate the profound philosophical distinctions and practical implications of these two dominant forms of governance.

Monarchy: The Sovereign's Crown and the Weight of One

Monarchy, in its purest form, signifies rule by a single individual, typically inheriting their position and holding supreme authority. Historically, this has been the most prevalent form of Government, rooted in traditions, divine right, or military conquest.

Philosophical Arguments for Monarchy:

- Stability and Continuity: Proponents, such as Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan, argued that a single, absolute sovereign could prevent civil strife and ensure order, providing a clear line of succession and avoiding the factionalism often seen in other forms of Government.

- Efficiency in Decision-Making: With power concentrated, decisions can be made swiftly and decisively, unburdened by the need for extensive consensus. This can be particularly advantageous in times of crisis.

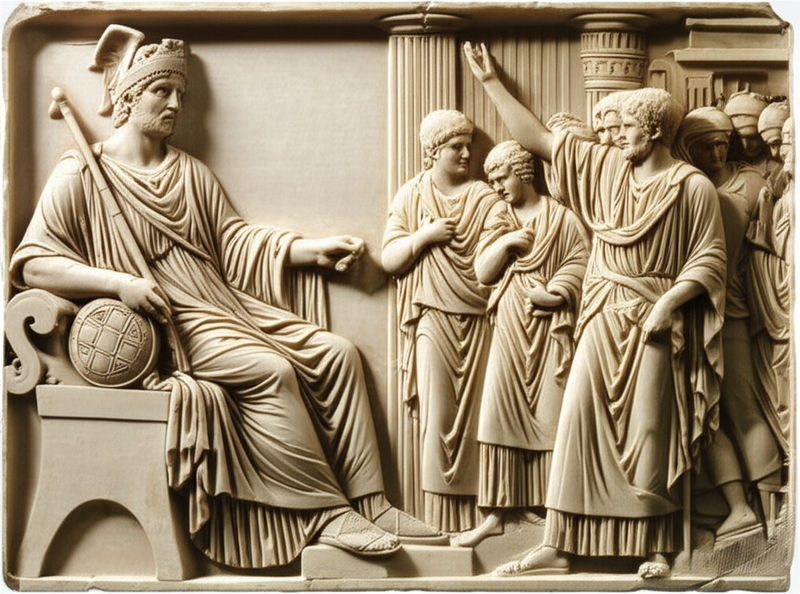

- The Philosopher-King Ideal: Plato, in his Republic, envisioned an ideal State ruled by a "philosopher-king"—a benevolent, wise, and just monarch who governs not by arbitrary whim, but by reason and for the good of the State. While a utopian ideal, it speaks to the potential for enlightened single rule.

- National Unity and Identity: A monarch can serve as a unifying symbol for the nation, embodying its history, traditions, and collective identity, transcending political divisions.

Critiques of Monarchy:

- Tyranny and Arbitrary Rule: The most significant danger of Monarchy is the potential for abuse of power. Without checks and balances, a monarch can become a tyrant, governing solely for personal gain or caprice, leading to oppression and injustice.

- Lack of Accountability: In absolute monarchies, the sovereign is often above the law, accountable to no one but themselves or, theoretically, to God. This can lead to unchecked power and a disregard for the welfare of the populace.

- Succession Issues: While intended to provide continuity, hereditary succession can also lead to incompetent or cruel rulers, or even violent disputes over the throne.

- Suppression of Individual Liberty: Absolute Monarchy often prioritizes the will of the ruler over the rights and freedoms of individual citizens.

Democracy: The People's Voice and the Power of Many

Democracy, derived from the Greek words "demos" (people) and "kratos" (power), represents a system of Government where power is vested in the people, who either directly exercise it or elect representatives to do so. Its roots trace back to ancient Athens, though modern forms differ significantly.

Philosophical Arguments for Democracy:

- Popular Sovereignty: Philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in The Social Contract, argued that legitimate Government derives its authority from the consent of the governed. The general will of the people should be the ultimate source of law.

- Protection of Individual Rights and Liberties: John Locke, in his Two Treatises of Government, posited that individuals possess inherent rights, and Government exists to protect these rights. Democracy, with its emphasis on constitutionalism and rule of law, is seen as the best mechanism for this protection.

- Accountability and Responsiveness: In a Democracy, leaders are accountable to the electorate and must periodically seek their mandate. This forces Government to be more responsive to the needs and desires of its citizens.

- Equality and Participation: Democracy theoretically offers all citizens an equal voice in political decision-making, fostering a sense of ownership and participation in the State.

- Encouragement of Deliberation: Democratic processes, through debate and discussion, can lead to more considered and robust policies, incorporating diverse perspectives.

Critiques of Democracy:

- Tyranny of the Majority: A significant concern, articulated by thinkers like Alexis de Tocqueville in Democracy in America, is that the majority can impose its will on minority groups, suppressing their rights and interests.

- Inefficiency and Instability: The need for consensus, debate, and electoral cycles can lead to slow decision-making, political gridlock, and frequent changes in policy, potentially undermining stability.

- Demagoguery and Populism: Democracy can be susceptible to charismatic but unprincipled leaders who exploit popular emotions and prejudices rather than engaging in rational discourse.

- Lack of Expertise: Critics argue that complex Government decisions require specialized knowledge that the general populace may lack, leading to suboptimal policies.

- Voter Apathy: In many Democracies, voter turnout can be low, raising questions about the true representativeness of the Government.

Comparing the Frameworks: A Snapshot of Governance

To better understand the inherent trade-offs, let's consider a direct comparison of key aspects of these two forms of Government:

| Feature | Monarchy (Absolute) | Democracy (Representative) |

|---|---|---|

| Source of Authority | Divine right, inheritance, tradition | Consent of the governed, popular sovereignty |

| Decision-Making | Centralized, swift, by one sovereign | Decentralized, deliberative, by elected representatives |

| Accountability | Limited (to God, conscience, or no one) | High (to the electorate, through elections and rule of law) |

| Citizen Role | Subjects, limited participation | Citizens, active participation through voting and advocacy |

| Stability | Potentially high (if succession is smooth) | Can be volatile (due to elections, factionalism) |

| Liberty | Variable, often limited by sovereign's will | Generally prioritized, protected by constitution/laws |

| Risk | Tyranny, arbitrary rule, incompetence | Tyranny of the majority, demagoguery, inefficiency |

The Evolving State: Beyond Pure Forms

It is crucial to recognize that pure forms of Monarchy and Democracy are rare in the modern world. Many contemporary States operate under hybrid systems. Constitutional monarchies, for instance, retain a monarch as a symbolic head of State while real political power rests with an elected Government, blending historical tradition with democratic principles. Similarly, no Democracy is truly direct; most are representative republics where citizens elect individuals to make decisions on their behalf.

The ongoing philosophical inquiry into governance continues to refine our understanding of these systems. As the State evolves in response to global challenges and technological advancements, the tension between efficient, centralized authority and broad, participatory Democracy remains a central theme for critical thought.

Conclusion: A Continuous Philosophical Endeavor

Ultimately, the study of Monarchy vs. Democracy is not merely an academic exercise but a vital inquiry into the very nature of human society and the pursuit of justice. Neither system offers a perfect blueprint for Government; each carries inherent strengths and vulnerabilities. The "best" form of governance is often contextual, depending on a society's history, culture, and the philosophical values it prioritizes. What remains constant is the imperative for continuous philosophical examination, ensuring that the structures of our State serve the collective good and uphold the dignity of its citizens. The dialogue initiated by the Great Books of the Western World persists, challenging us to think deeply about how we are governed and how we, in turn, govern ourselves.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato Aristotle Monarchy Democracy Comparison Philosophy""

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Locke Rousseau Social Contract Theories of Government""