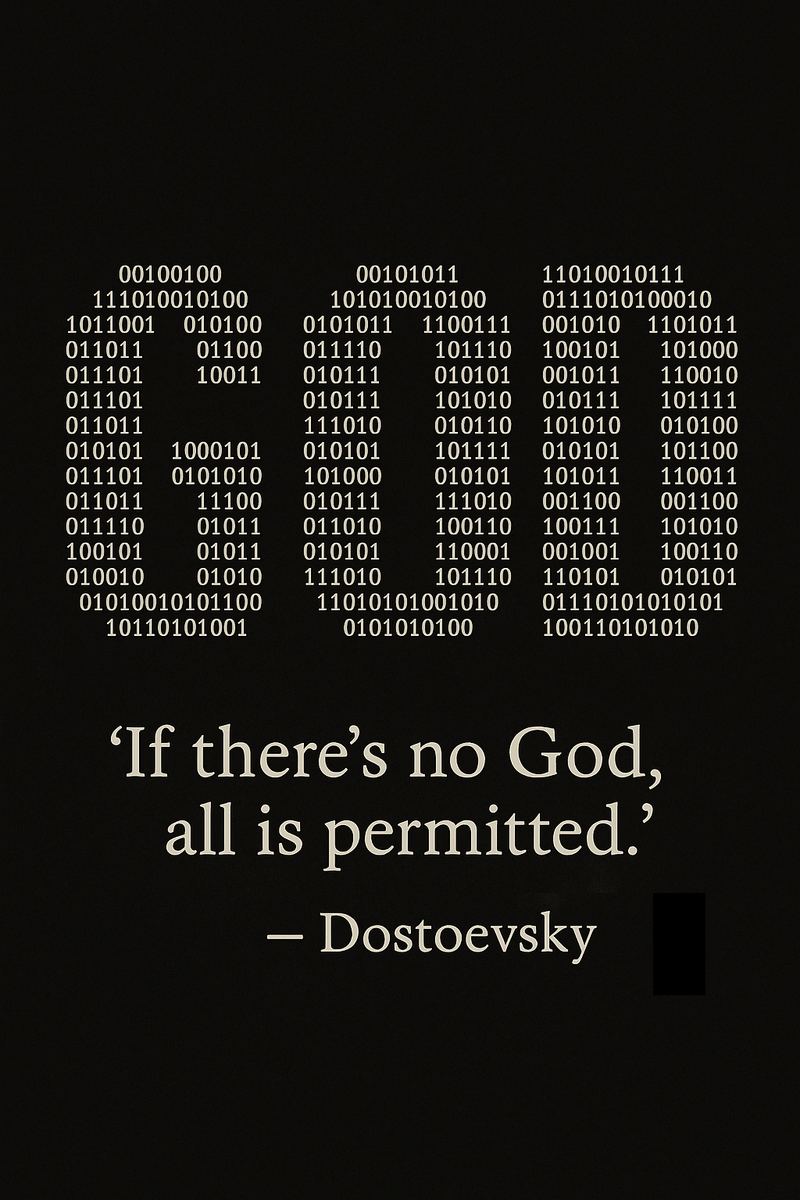

“If there’s no God, all is permitted.” — Dostoevsky

Stephen Hawking said the same thing a different way: the universe can, in principle, be explained without a creator. Put the two together and you get the paradox that has been gnawing at us since we could count—mathematicians in one hand, priests in the other, and all of us squinting at the same landscape.

Here’s the blunt thesis: the universe behaves like information. Religions are cultural compression algorithms that data meaningful. Physics writes the rules; ritual gives the rules an edge for living. Neither side gets the last word. Both are human ways of coping with an ocean of numbers.

1 — Math first, poetry next

Look at what scientists do. They measure, reduce, and predict. They take a riot of observations and ally them into tidy symbols: ψ, ℏ, Σ, the spin quantum number that is either “up” or “down.” At the level of electrons, the world literally behaves like bits. Spin is binary. Everything that’s measurable can be enumerated. Wavelengths, masses, half-lives—numbers.

If you accept that (and physics keeps giving us reasons to), then the universe is, in one sense, a code-base. Equations are the API. Laws of physics are compression rules that let us predict behavior with fewer symbols. They aren’t stories; they’re usable maps.

But maps aren’t meaning. Ask any person who has stood at a bedside or at a burial. The map doesn’t tell you how to hold a hand. That’s where religion and myth live. Humans transform cold data into narratives—stories that guide action, bind communities, and scaffold courage when probabilities look ugly.

2 — Religion as symbolic compression

Religion is an information strategy. It reduces complexity into ritual and rule. Different faiths are like different languages for describing the same human facts: birth, death, suffering, belonging. There are roughly four thousand religious expressions across cultures. That’s not proof of God’s absence; it’s proof of our capacity to encode meaning in diverse ways.

Numbers tell us something important here: around 85% of the world identifies with a religion. That’s a statistical fact, and statistics are stubborn. Majority doesn’t confer metaphysical truth, but it does tell us what humans do when they face scale and uncertainty: they pattern-match, aggregate, and externalize meaning. If a scientist and a believer both want to reduce entropy—the former via equations, the latter via covenant—then they’re doing the same fundamental work in different registers.

3 — So what is God, if anything?

If you insist on a name, call God the organizing pattern—the algorithm that makes the compression possible. That’s slippery theology dressed as math, but it’s useful. Imagine God as the structure that lets equations be consistent, the reason the code compiles. Or imagine God as the sum of human answers to the question: “How do we live when the numbers aren’t kind?”

Either reading strips God of some supernatural baggage and gives Him (or It) a different dignity: not a capricious supernatural landlord but a principle, a shared human response to data. That doesn’t disprove miracles; it frames them. A miraculous recovery could be an improbably rare event in the statistical tail, or it could be an otherwise-unknown mechanism—either way, it’s an event that forces our models to grow.

4 — Counting faith, not policing it

Critics say: “If everything reduces to numbers, faith is obsolete.” To which the honest reply is: math doesn’t remove the need for meaning. It clarifies constraints. Physics can tell you what’s possible; it can’t tell you what’s worth doing. That’s a value judgment—a human variable outside the equation until we feed it into the model.

If the atheist says “1+1=2; therefore faith is wrong,” they miss the point that faith isn’t an arithmetic mistake; it’s an interpretive choice. The believer says “1+1=2 because God ordained it”—that’s a metaphysical claim layered over an arithmetic fact. Both sides use the same math; they disagree on the interpretive layer.

5 — Practical consequences

Why does this matter? Because the way we encode meaning shapes institutions and choices. Treat belief as an information system and you get different policy moves:

• Public health: treat ritual as social glue that can amplify or hinder campaigns.

• Education: teach statistical literacy alongside ethical frameworks.

• Technology: design systems that respect human narrative—data without context is tyrannical.

When we take seriously that the world is both number and story, we avoid two traps: scientism (pretending equations answer "ought") and dogmatism (pretending rituals answer "how"). Both are brittle. Both snap when reality gets heavy.

6 — A simple test

If you want a pragmatic test of whether a belief-system is useful, ask: does it improve the model’s outputs for living? Does it help people act, sustain communities, and reduce needless suffering? If it does, it’s doing work—even if the metaphysical claim behind it is wrong. The debate about God then becomes secondary to the conversation about function.

Conclusion — A modest plea

Stop treating science and faith as enemies. Treat them as different compression tools built by a single species that’s terrifyingly good at pattern-recognition and miserably bad at feeling satisfied.

We live in a universe that counts. We are creatures that need to sing. The math gives us the skeleton; religion, poetry, art, and ritual give us the flesh. Try to keep your calculus honest and your metaphors humane. If God is a function, fine—call the function what you like. Just don’t confuse the derivative with the thing you love.

God, if you’re watching, you’d better be good at linear algebra. We’re counting on the results.