The Ascendance of Observation: How Induction Forges Scientific Law

In the grand tapestry of human knowledge, few threads are as fundamental and enduring as the process of induction. It is the very bedrock upon which our understanding of the natural world is built, the essential reasoning that allows us to move from the chaotic multiplicity of individual observations to the elegant simplicity of scientific law. This article explores how this powerful mode of thought, rooted in empirical experience, systematically constructs the universal principles that govern our universe.

The Inductive Leap: From Particulars to Universals

At its heart, induction is a form of logical reasoning where specific observations lead to a general conclusion. Unlike deduction, which moves from general premises to specific conclusions, induction makes a leap of faith, inferring that what has been observed to be true in many instances will likely be true in all similar instances. This isn't a guarantee of truth, but rather a robust statement of probability and predictive power, foundational for all science.

Consider the simple act of observing that the sun rises in the east every morning. After countless such observations, we induce that the sun always rises in the east. This isn't a logical necessity derived from an axiom, but an empirical generalization.

The Pillars of Inductive Scientific Inquiry

The journey from raw data to a codified scientific law is a meticulous process, heavily reliant on inductive principles.

1. Observation and Data Collection

The starting point for any scientific endeavor is careful, systematic observation. This involves gathering data about phenomena, noting patterns, and identifying variables. For instance, early astronomers meticulously charted the movements of celestial bodies, compiling vast amounts of data without necessarily understanding the underlying causes.

2. Pattern Recognition and Hypothesis Formulation

Once sufficient data is collected, the inductive mind seeks patterns and regularities. If every observed instance of X is followed by Y, then it's reasonable to hypothesize that X causes Y, or at least that they are consistently correlated. This leads to the formulation of a hypothesis – a testable, educated guess about the relationship between phenomena.

- Example: Observing that all known objects fall towards the Earth when dropped leads to the hypothesis that there is a force attracting all objects to the Earth.

3. Repeated Experimentation and Verification

A single observation, no matter how compelling, rarely suffices for scientific law. The inductive process demands repetition. Scientists design experiments to test hypotheses under controlled conditions, seeking to confirm the observed patterns across a wide range of circumstances. The more a hypothesis is consistently supported by empirical evidence, the stronger its inductive backing becomes.

4. Generalization and Predictive Power

As a hypothesis withstands repeated testing and is confirmed across diverse contexts, it begins to gain the status of a generalization. This generalization isn't just a description of past events; it carries significant predictive power. If we induce that "all metals expand when heated," we can predict that a new, unobserved metal will also expand when heated. This ability to predict future occurrences is a hallmark of robust scientific reasoning.

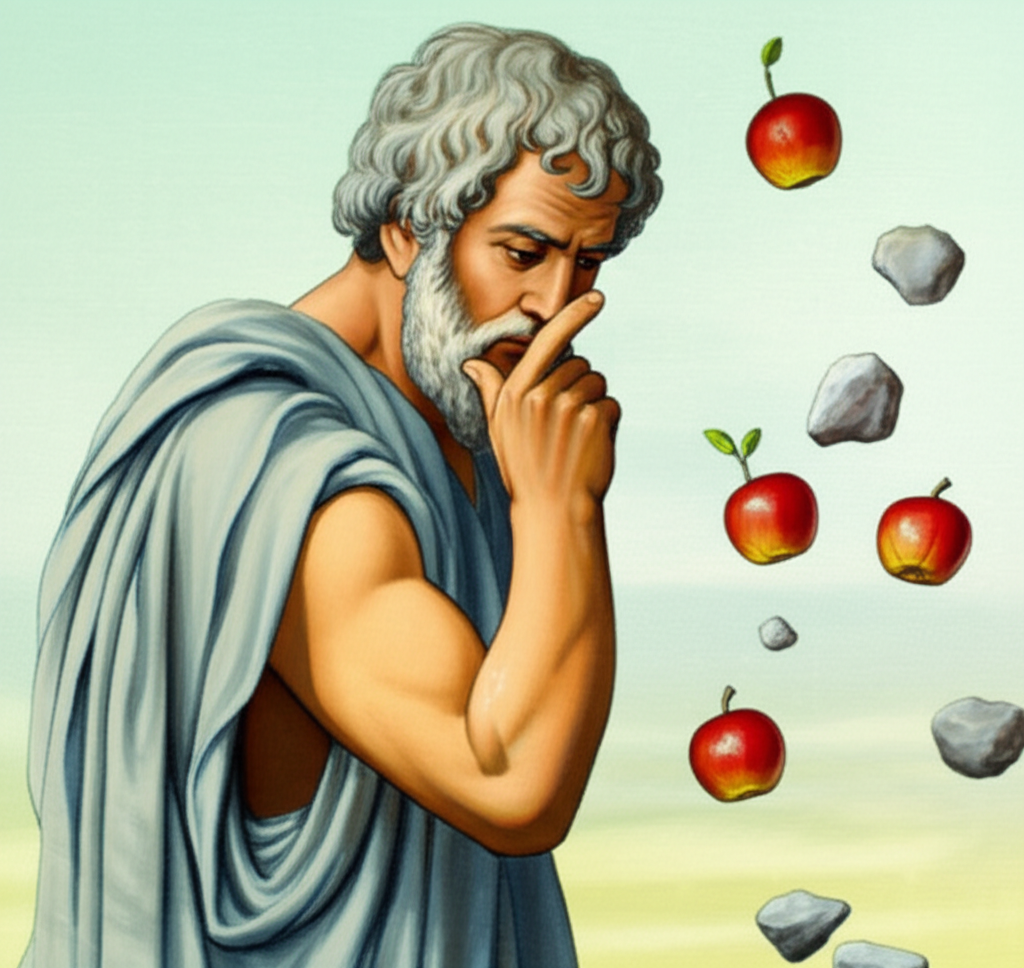

with a thoughtful expression, surrounded by scrolls and rudimentary scientific instruments. The background shows a transition from specific observations (individual falling objects) to a generalized concept (a gravitational pull represented by subtle lines converging towards the Earth), visually representing the inductive leap.)

with a thoughtful expression, surrounded by scrolls and rudimentary scientific instruments. The background shows a transition from specific observations (individual falling objects) to a generalized concept (a gravitational pull represented by subtle lines converging towards the Earth), visually representing the inductive leap.)

From Generalization to Scientific Law: The Apex of Induction

When a generalization has been extensively tested, consistently verified, and demonstrates universal applicability within its defined scope, it can ascend to the status of a scientific law.

Characteristics of a Scientific Law:

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Universality | Applies everywhere and always under the specified conditions. |

| Brevity/Simplicity | Often expressed as a concise mathematical equation or a short verbal statement. |

| Empirical Basis | Derived from and consistently supported by extensive observation and experimentation. |

| Predictive Power | Accurately forecasts future events or behaviors of phenomena. |

| Non-Explanatory | Describes what happens, but typically not why it happens (that's the domain of theories). |

Think of Newton's Laws of Motion. These are not mere descriptions; they are predictive statements about how objects behave under certain forces. They emerged from countless observations and experiments, culminating in a general formulation that holds true across a vast range of phenomena. While Newton didn't initially understand why gravity worked (that came with Einstein's theory of relativity), his laws precisely described how it worked, a triumph of inductive reasoning.

The Philosophical Underpinnings: Lessons from the Great Books

The "problem of induction" has fascinated philosophers for centuries, notably highlighted by David Hume in the Great Books of the Western World. Hume argued that no matter how many times we observe an event, we can never logically prove that it will always occur in the future. The sun has risen every day, but this doesn't logically guarantee it will rise tomorrow. This skepticism forces us to acknowledge that inductive conclusions, while incredibly powerful and reliable for science, are not logically infallible truths like deductive conclusions.

Despite Hume's challenge, thinkers from Aristotle, who meticulously categorized observations of the natural world, to Francis Bacon, who advocated for an empirical, inductive approach to knowledge, recognized the indispensable role of induction in building knowledge. For Bacon, the scientific method itself was largely an inductive enterprise, moving from specific experiments to broader generalizations.

The Indispensable Tool of Science

While the philosophical "problem of induction" reminds us of the inherent limitations of empirical reasoning, it does not diminish its practical utility. In science, induction is not about absolute certainty but about accumulating evidence to achieve the highest possible degree of probability and reliability. It is the engine that drives discovery, allowing us to:

- Formulate Hypotheses: Based on observed patterns.

- Develop Theories: Explanatory frameworks built upon confirmed laws.

- Create Technologies: Applying laws to practical problems.

- Advance Understanding: Continually refining our grasp of natural phenomena.

Without the inductive leap, science would be reduced to a mere collection of isolated facts, unable to generalize, predict, or build the comprehensive laws that allow us to navigate and understand our complex world. It is through this patient, empirical journey that observation transforms into principle, and specific events illuminate universal truths.

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Problem of Induction Explained""

📹 Related Video: SOCRATES ON: The Unexamined Life

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Francis Bacon Inductive Method""