Why Does a Rhetorical Question Prompt Silence?

Either Oar - A Relativistic Rhetorical Device Made Material

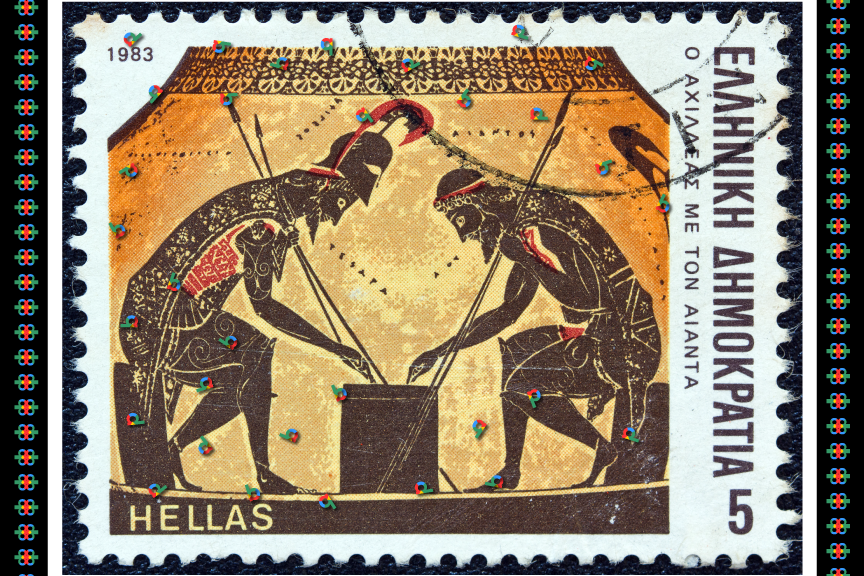

Setting: A boundless, echoing space, not quite dark, not quite light. Sophia stands near an object that looks like a magnificent, polished ship's oar, split perfectly down the middle, with each half resting on a pedestal. Plato appears across from her.

Sophia: Welcome, Plato. You seem to be admiring the vessel. Or perhaps, the means of its steering?

Plato: It is the tool that intrigues me, Sophia. It is elegant, yet so profoundly practical. A single implement, so capable of directing a course. I’ve always held that the most powerful form of guidance, the most effective ruling of the human spirit, comes not from physical force, but from the mastery of persuasion—from the spoken and written word. To steer the soul is to steer the state.

Sophia: That power you describe, to command the mind's direction, is immense. But look closely at the object between us. What do you see?

Plato: I see an oar, broken or perhaps deliberately cleaved. Two halves.

Sophia: Precisely. It is the material form of a relativistic rhetorical device, Plato. One that suggests that while the art of steering is vital, the direction itself depends on which half of the oar you choose to use—which reality you choose to acknowledge. The same words that can lead people toward the light of truth and ideal forms can, in other hands, push them toward comforting shadows and self-serving deceits.

Plato: A heavy burden, then, for the philosopher who must wield this device. If the goal is not merely influence, but good influence, the speaker must first master truth, lest he become nothing more than a sophist pushing a favored current.

Sophia: Indeed. The wise wielder must not only know how to move the minds of others, but also why—and toward what end. The Oar has two sides, Plato, but the sea we are on has a compass.

Sophia: It seems we have another guest, Plato.

(Aristotle appears, looking thoughtful and examining the two halves of the oar.)

Aristotle: An excellent dissection, Sophia. You’ve taken a concept and given it a palpable form.

Sophia: Welcome, Aristotle. Your thoughts?

Aristotle: Well, Plato is concerned with the highest application of this steering power, how it directs the soul. But I’ve always been more focused on the engine of the device itself—how it operates here on the ground. The way a speaker builds their case, the logical structure, the emotional appeal, the credibility they project.

Plato: (Nodding) The means of the steering.

Aristotle: Precisely. I see these two halves of the oar not just as two different possible destinations, but as the raw materials of the act itself. To persuade effectively, one must understand both the currents of logic and the winds of emotion. A speaker who uses only one half will find the journey slow and clumsy. To be truly compelling, to move minds, you need the craft of argument—what I call the available means of persuasion. The power is in the balance, or at least, the strategic deployment of both.

Sophia: So you see the two halves not as a fork in the road, but as complementary forces required for true momentum?

Aristotle: The perfect metaphor. One must be able to argue any side of a case, not to justify falsehood, but to understand its appeal and structure a superior truth. The rhetorical device must be dual to be fully effective.

Sophia: An excellent point. Mastery of the technique itself, regardless of immediate intent, grants the power. The wisdom, then, lies in the choice of the stroke.

Sophia: So, we have established that rhetoric is the rule of the mind (Plato), and that its power lies in mastering the complete set of tools, the whole device (Aristotle). But what about its application in the everyday, the common world?

(Machiavelli appears, his eyes sharp, looking primarily at the handle of the oar.)

Machiavelli: Forgive my interruption, but you discuss power. I am drawn to that.

Sophia: Welcome, Machiavelli. What does this relativistic oar suggest to you?

Machiavelli: It suggests the necessity of expediency. All this talk of truth and ideal forms is well and good, but the common man, the citizen, is not ruled by philosophy, but by the practicalities of governance. If the goal is effective leadership—if the prince is to maintain his state—he must use the half of the oar that best serves the immediate need.

Rhetoric is the art of ruling the minds of men.

— Plato (c. 424 BC to c. 348 BC)

Plato: So, you advocate for steering toward falsehood if it maintains order?

Machiavelli: I advocate for using the most effective argument to achieve the most stable outcome. If an emotional, persuasive appeal (a lie, if you must) ensures the people's compliance and the state's security, then that is the correct stroke of the oar. The rhetoric of the ruler is simply a tool of control. It doesn't matter if the oar is split between truth and necessary deception, as long as the boat is stable and the captain is in charge.

Aristotle: You acknowledge the complete set of means, but dismiss the ethos of the speaker in favor of the goal.

Machiavelli: I acknowledge that the goal—the safety and success of the state—is the ultimate ethos. When the ship is taking on water, you don't debate the philosophy of steering; you row with the half that saves the ship. This device, Sophia, is the perfect material representation of a ruler's necessity: two options, one essential objective.

Sophia: (Picking up one half of the oar and looking from Plato to Machiavelli) So we have the ideal of truthful guidance and the pragmatism of necessary control. The art of ruling the minds of men, as Plato first noted, is a choice of direction. It is a continuous decision of which reality to emphasize—which way to persuade the populace to face. The relativity isn't in the tool itself, but in the heart of the one who chooses which oar to take up.

Do you think a rhetoric focused purely on expediency, as Machiavelli suggests, can ever be truly stable, or must it eventually collapse without a foundation in truth?

The planksip Writers' Cooperative is proud to sponsor an exciting article rewriting competition where you can win part of over $750,000 in available prize money.

Figures of Speech Collection Personified

Our editorial instructions for your contest submission are simple: incorporate the quotes and imagery from the above article into your submission.

What emerges is entirely up to you!

Winners receive $500 per winning entry multiplied by the article's featured quotes. Our largest prize is $8,000 for rewriting the following article;

At planksip, we believe in changing the way people engage—at least, that's the Idea (ἰδέα). By becoming a member of our thought-provoking community, you'll have the chance to win incredible prizes and access our extensive network of media outlets, which will amplify your voice as a thought leader. Your membership truly matters!