Wealth Distribution and Economic Justice: A Philosophical Inquiry

The question of how wealth should be distributed within a society is not merely an economic concern; it is, at its core, a profound philosophical challenge rooted in our understanding of justice. From ancient city-states to modern global economies, thinkers have grappled with the ethical implications of economic inequality, the role of labor in generating value, and the legitimate power of the state to intervene. This article explores the historical arc of these debates, drawing upon foundational texts to illuminate the enduring complexities of achieving economic justice in a world defined by unequal access to wealth.

The Enduring Dilemma: What is Economic Justice?

Economic justice asks not just "how much do people have?" but "how should people have what they have?" It delves into the fairness of economic arrangements, the distribution of resources, opportunities, and burdens. For centuries, philosophers have wrestled with the principles that ought to govern the allocation of societal wealth, questioning whether current distributions are natural, earned, or the result of unjust systems.

Ancient Foundations: Virtue, Property, and the Polis

The earliest systematic explorations of wealth and its distribution can be found in the works of classical Greek philosophers.

-

Plato's Ideal State: In his Republic, Plato envisioned a society where the ruling class (Guardians) would hold no private property, advocating for a form of communal living to prevent corruption and ensure their focus remained on the common good. For Plato, justice in the state was analogous to harmony in the soul, with each part fulfilling its proper function. While he didn't advocate for complete egalitarianism across all classes, his proposals for the Guardians highlighted a concern that excessive wealth could undermine civic virtue.

-

Aristotle on Property and Distribution: Aristotle, in his Politics and Nicomachean Ethics, provided a more nuanced view. He recognized the practical benefits of private property for individual incentive and responsibility, but also cautioned against its extremes. He distinguished between different forms of justice, including distributive justice, which concerns the fair allocation of honors, goods, and wealth according to merit. Aristotle argued that the state should aim for a substantial middle class to ensure stability and prevent the polarization of rich and poor, which he saw as a threat to the polis.

The Rise of Individual Rights and the Social Contract

With the Enlightenment, the focus shifted from communal virtue to individual rights and the origins of political authority.

-

John Locke and the Genesis of Property through Labor: John Locke, in his Second Treatise of Government, posited that individuals acquire property through their labor. When a person mixes their labor with unowned natural resources, those resources become their property. This foundational idea links wealth directly to individual effort. However, Locke also introduced provisos: one must leave "enough, and as good" for others, and one should not waste what one acquires. While legitimizing private property, Locke's framework implicitly raised questions about the accumulation of vast wealth and its impact on those who could no longer find unowned resources to mix their labor with.

-

Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the Critique of Inequality: Rousseau, in his Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men, offered a scathing critique of private property, which he saw as the root cause of societal inequality and moral degradation. He argued that the establishment of private property led to the creation of civil society and laws, which were primarily designed to protect the wealth of the rich. In The Social Contract, Rousseau argued that the state, guided by the "general will," has a legitimate role in ensuring a degree of economic equality to preserve liberty and prevent the domination of some by others.

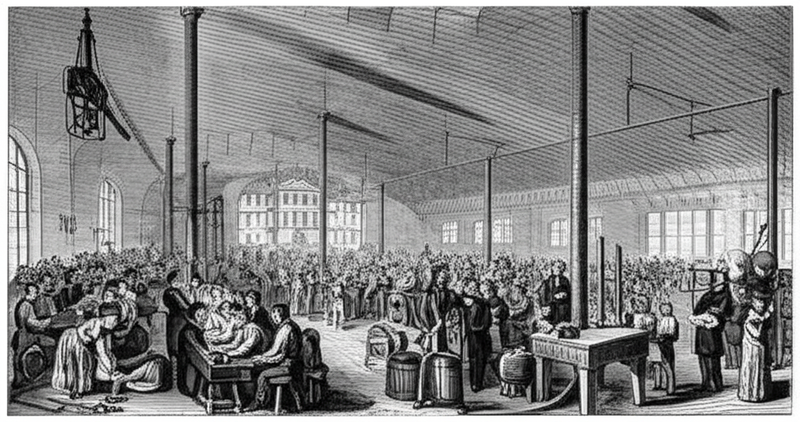

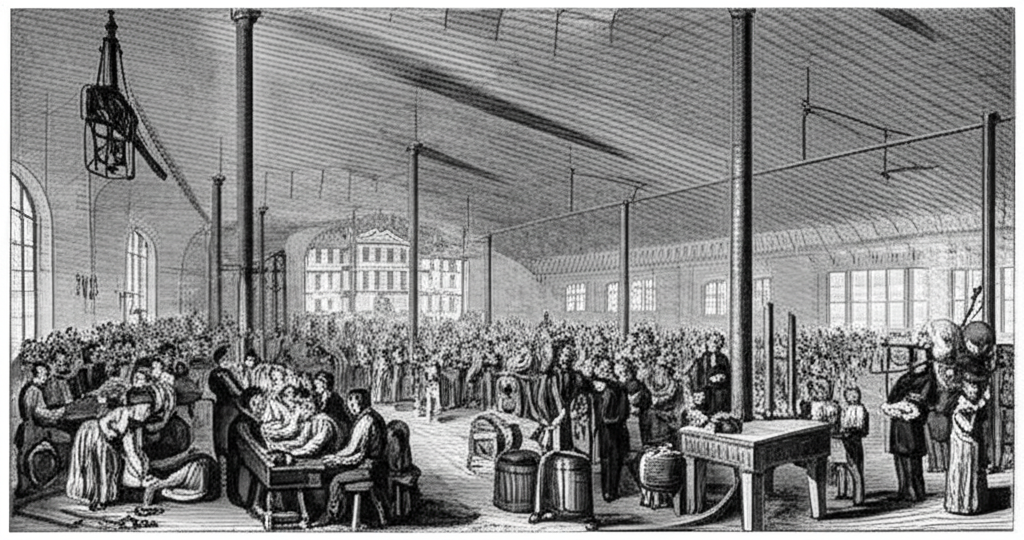

The Industrial Age and the Critique of Capitalism

The dramatic societal changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution sparked new, radical philosophical inquiries into wealth, labor, and justice.

- Karl Marx: Labor, Exploitation, and the State: Karl Marx, drawing heavily on the labor theory of value, argued that capitalism inherently creates an unjust distribution of wealth. In Das Kapital, he contended that labor is the source of all value, but under capitalism, workers (the proletariat) are exploited because they do not receive the full value of their labor. Instead, capitalists appropriate "surplus value" as profit. Marx saw the state as an instrument of the ruling class, serving to protect the interests of the property owners. For Marx, true economic justice could only be achieved through a revolutionary transformation leading to a classless society where the means of production are communally owned.

Core Philosophical Debates on Wealth and Justice

The historical trajectory reveals several persistent philosophical tensions:

-

Meritocracy vs. Egalitarianism:

- Meritocracy: Advocates argue that wealth should be distributed based on individual merit, effort, talent, and contribution. Those who work harder, innovate more, or provide more valuable services deserve greater rewards.

- Egalitarianism: Proponents argue that a just society should strive for a more equal distribution of wealth and resources, often emphasizing equality of opportunity or even equality of outcome, believing that vast disparities undermine social cohesion and true liberty.

-

The Nature of Labor and Compensation:

- Is labor inherently valuable, regardless of its market price?

- How should compensation be determined? By market forces, by need, or by a societal assessment of its contribution?

- What constitutes a "fair wage" or a "living wage"?

-

The Legitimate Role of the State:

- Should the state merely protect property rights and enforce contracts (minimal state)?

- Does the state have a duty to redistribute wealth to ensure a basic standard of living or to reduce inequality (welfare state)?

- Is the state itself a tool of economic injustice, or a necessary arbiter for justice?

Table: Perspectives on the State's Role in Wealth Distribution

| Philosopher/School | Primary View on Wealth Acquisition | State's Role in Wealth Distribution | Key Concern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plato | Communal for Guardians; Private for others | Regulate for civic virtue; prevent extremes | Social harmony; corruption |

| Aristotle | Private property; earned by merit | Promote a strong middle class; prevent polarization | Political stability; civic virtue |

| Locke | Acquired through labor; natural right | Protect property rights; enforce contracts | Individual liberty; natural rights |

| Rousseau | Origin of inequality; corrupting | Mitigate extremes of wealth; uphold general will | Equality; social contract |

| Marx | Exploitation of labor by capital | Overthrow capitalist state; establish communal ownership | Class struggle; exploitation |

Conclusion: An Ongoing Philosophical Imperative

The debate surrounding wealth distribution and economic justice is far from settled. It forces us to confront fundamental questions about human nature, the purpose of society, and the ethical boundaries of economic activity. From ancient Greece to the Enlightenment and into the industrial age, philosophers have provided frameworks for understanding the complex interplay between wealth, labor, and the state. As societies continue to evolve, marked by new technologies and globalized economies, the imperative to seek and define economic justice remains a central, urgent task for philosophical inquiry.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Justice: What's The Right Thing To Do? Episode 8: 'Whose Title Is It?'""

2. ## 📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Karl Marx & Conflict Theory: Crash Course Sociology #6""