We All Have to Eat

Agony is Crippling

(The scene is a quiet, minimalist space. There are three simple chairs arranged in a loose circle. Light, soft and sourceless, fills the room. SOPHIA sits calmly, observing MARY, who stares at her own hands, and BERNARD, who looks on with a thoughtful expression.)

Sophia: Let us begin with the proposition before us. A simple, yet terrible, statement: Agony is Crippling. Mary, your spirit has walked through that fire. Tell us of that landscape.

Mary: (Without looking up) It is not a landscape you walk through. It is a chamber from which there is no exit. The pain is not an event; it becomes the architect of your reality. Every joy that tries to enter is interrogated at the door and found wanting. Every memory becomes a witness for the prosecution of your own happiness. The suffering is insatiable, Sophia. It finds nourishment in everything—a strain of music, a child's laughter, the silence of an empty room. It twists it all into new fuel for its own fire, ensuring you have no moment of peace, no shelter from the storm within. It is not a wound. It is a lens through which the entire world is warped into a singular, monstrous shape of your own misery.

Sophia: It paralyzes the will, then. It consumes all other possible ways of being.

Mary: It leaves nothing else. You are hollowed out, and the agony builds its nest inside.

The agony of my feelings allowed me no respite; no incident occurred from which my rage and misery could not extract its food.

— Mary Shelley (1797-1851)

(Sophia turns her calm gaze to Bernard, who has been listening intently, his brow furrowed.)

Sophia: And yet, Bernard, you have looked upon humanity and seen something else. You have weighed our creations of iron and stone against our own essence. What have you found?

Bernard: I have found a profound paradox. I do not dispute the prison Mary describes. The agonies she speaks of are real forces, powerful enough to shatter civilizations. But in all our ingenuity, in all the materials we have forged and refined, we have never engineered a substance with the sheer durability of the human spirit. It can be bent to the breaking point, subjected to pressures that would pulverize granite, and seared by fires that would melt steel. And yet, it endures.

Mary: (Looks up, her eyes flashing with a pained fire) Endures as what, Bernard? A scarred and twisted thing? A ruin that simply refuses to collapse? You speak of resilience as if it is a victory. Sometimes, it is merely a prolonged defeat. What is the virtue of enduring when the thing that endures is no longer recognizable as the self you once were?

Bernard: The virtue is in the capacity for renewal, Mary. Resilience is not the absence of scars; it is the ability to grow around them. The spirit is not rigid like a diamond, which shatters under a precise blow. It is something more pliable, more alive. It can be wounded, yes, terribly so. It can be crippled, as Sophia says. But inherent in its nature is a capacity to mend, to integrate the damage, to become something new—not erasing the pain, but weaving it into a tapestry of greater depth and strength. The crippling is the event; the resilience is the essence.

Sophia: (Leaning forward slightly, bringing their perspectives together) So, here is the heart of it. Mary, you describe the subjective, all-consuming experience of agony—a state of being that feels absolute and eternal from within. And Bernard, you describe the objective, inherent quality of the human spirit—a potential that exists even when it cannot be felt.

(She pauses, letting the two ideas hang in the air.)

Sophia: Is it possible that both are simultaneously true? That agony is crippling, and the human spirit is resilient? The paradox is not a contradiction; it is a process. The blow that cripples does not annihilate the spirit's nature. Rather, it reveals it. The searing heat of Mary’s endless pain is the very forge in which Bernard’s unbreakable spirit is tested and, ultimately, proven. The agony is the force that strikes, and the spirit's resilience is its refusal to be utterly extinguished by the strike. One cannot be truly known without the other.

Man never made any material as resilient as the human spirit.

— Bernard Williams (1929-2003)

Mary: (Her gaze softens, a flicker of understanding in her eyes) So… the respite I could never find was not meant to be an escape from the pain.

Bernard: Perhaps the respite is the quiet discovery, long after the fire has cooled, that you are still there. Changed, scarred, but present.

Sophia: Precisely. The spirit's triumph is not that it feels no pain. It is that it can be crippled by the most profound agony imaginable and still, somehow, find a way to stand back up. Not as it was, but as it has become—forged in the heart of its own suffering.

The planksip Writers' Cooperative is proud to sponsor an exciting article rewriting competition where you can win part of over $750,000 in available prize money.

Figures of Speech Collection Personified

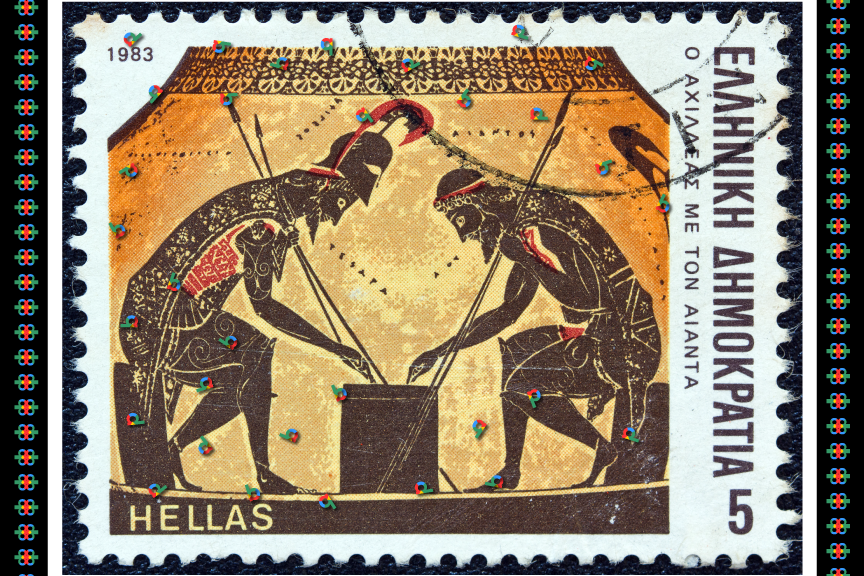

Our editorial instructions for your contest submission are simple: incorporate the quotes and imagery from the above article into your submission.

What emerges is entirely up to you!

Winners receive $500 per winning entry multiplied by the article's featured quotes. Our largest prize is $8,000 for rewriting the following article;

At planksip, we believe in changing the way people engage—at least, that's the Idea (ἰδέα). By becoming a member of our thought-provoking community, you'll have the chance to win incredible prizes and access our extensive network of media outlets, which will amplify your voice as a thought leader. Your membership truly matters!