The Virtue of Temperance Over Desire: A Path to Self-Mastery

Summary: In a world often driven by immediate gratification, the ancient virtue of temperance offers a profound counter-narrative. This article explores temperance not as a rigid asceticism, but as the cultivated ability of the Will to intelligently moderate our desires, leading to a harmonious inner life and true freedom. Drawing from the wisdom embedded in the Great Books of the Western World, we will delve into how temperance stands as a bulwark against the excesses of vice, fostering well-being and genuine human flourishing.

The Ancient Call for Self-Mastery: An Introduction

From the earliest philosophical inquiries, humanity has grappled with the powerful, often unruly, force of desire. Whether for food, pleasure, wealth, or power, these internal impulses can propel us to great achievements or drag us into profound suffering. The challenge, as understood by the great thinkers of antiquity, is not to eradicate desire—an impossible and perhaps undesirable feat—but to master it. This mastery is precisely where the virtue of temperance finds its enduring relevance. It is the art of discerning wisdom, allowing our rational Will to guide our appetites rather than being enslaved by them.

Defining Temperance: A Virtue, Not an Absence

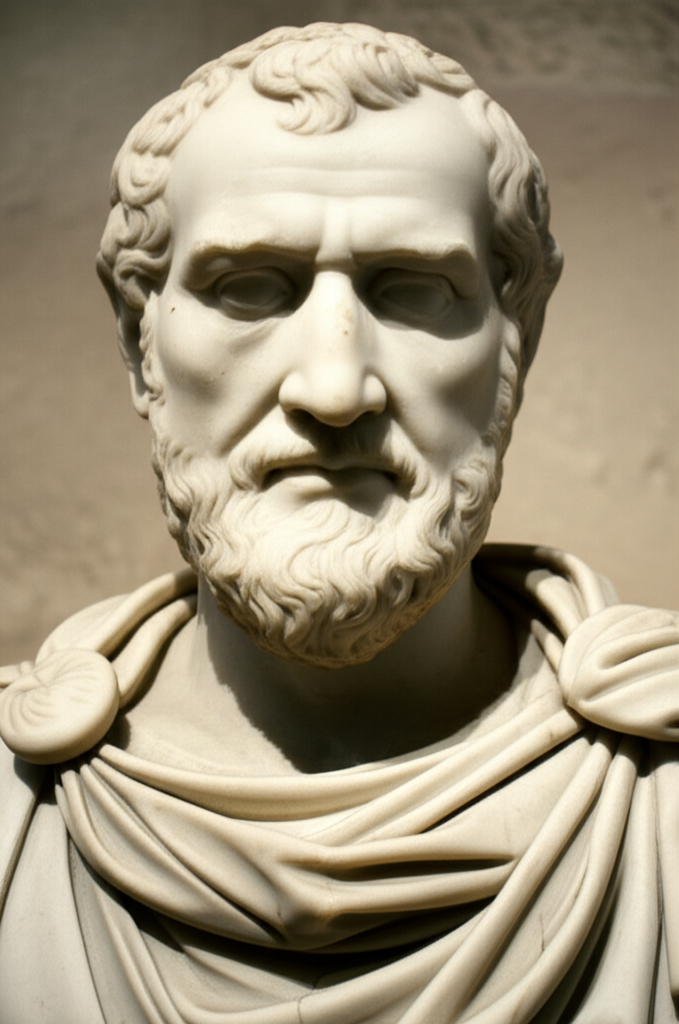

Temperance (Greek: sophrosyne, Latin: temperantia) is often misunderstood as mere abstinence or self-denial. However, its true meaning, as illuminated by philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, is far richer. It is the intelligent moderation of desires and pleasures, a harmonious balance rather than a suppression.

- Temperance is not:

- Complete renunciation of pleasure.

- An absence of desire.

- A joyless existence.

- Temperance is:

- The appropriate enjoyment of pleasure.

- Self-control and inner discipline.

- A rational ordering of appetites.

- A virtue that enables flourishing.

Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, places temperance within his framework of the Golden Mean, defining it as the mean between the vice of insensibility (too little desire/pleasure) and intemperance (too much desire/pleasure). It is a disposition to feel desires and pleasures in the right way, at the right time, and to the right extent.

The Nature of Desire: A Double-Edged Sword

Desire is intrinsic to human experience. It fuels our ambition, drives our creativity, and connects us to the world around us. Yet, unchecked, it can become a relentless master, leading to addiction, greed, and moral decay. The Great Books consistently explore this duality:

Table: The Dual Nature of Desire

| Aspect of Desire | Potential for Virtue (when temperate) | Potential for Vice (when intemperate) |

|---|---|---|

| For sustenance | Health, vitality, appreciation of simple things | Gluttony, sloth, illness |

| For pleasure | Joy, connection, aesthetic appreciation | Hedonism, addiction, superficiality |

| For possessions | Security, generosity, means for good works | Greed, envy, materialism, exploitation |

| For recognition | Self-respect, motivation, leadership | Vanity, arrogance, tyranny |

| For knowledge | Wisdom, understanding, progress | Intellectual pride, dogma, detachment |

Plato's allegory of the charioteer in Phaedrus perfectly illustrates this dynamic. The charioteer (reason/Will) must guide two horses: one noble and well-behaved (spirit/honor), and the other unruly and impetuous (appetite/desire). Temperance is the skill of the charioteer in keeping the unruly horse in check, ensuring the soul moves harmoniously towards its true good.

The Role of Will in Cultivating Temperance

The bridge between raw desire and the cultivated virtue of temperance is the Will. It is our capacity for rational choice, for deliberate action, and for self-control. Without a strong and rightly-directed Will, we are merely slaves to our impulses, perpetually chasing the next fleeting pleasure or avoiding discomfort.

Philosophers like Augustine and Aquinas emphasized the crucial role of the Will in moral life. For them, freedom is not the ability to do whatever we want, but the ability to choose the good. Temperance, therefore, is an act of freedom—a conscious decision to align our actions with reason and our higher purpose, rather than being swayed by every passing whim. It requires:

- Self-awareness: Understanding our own desires and their potential pitfalls.

- Discipline: The consistent practice of choosing moderation.

- Foresight: Considering the long-term consequences of our choices.

Through the exercise of Will, we don't extinguish desire, but rather integrate it into a balanced and flourishing life. We learn to appreciate pleasures without being consumed by them, to pursue goals without being enslaved by ambition.

Temperance in Practice: Beyond Abstinence

Temperance is not an abstract concept; it is a lived reality that permeates every aspect of existence. It is about exercising moderation in all things that pertain to our physical and emotional well-being.

- Eating and Drinking: Temperance is enjoying food and drink for nourishment and pleasure, without succumbing to gluttony or excess. It is knowing when to stop, not because of external rules, but internal wisdom.

- Speech: It means speaking truthfully, kindly, and only when necessary, avoiding gossip, boastfulness, or harmful words.

- Spending: Temperance guides us to manage our resources wisely, distinguishing between needs and wants, and avoiding extravagance or avarice.

- Leisure: It involves balancing rest and activity, ensuring that relaxation rejuvenates rather than debilitates.

The Philosophical Lineage of Temperance

The advocacy for temperance echoes through the Great Books of the Western World, a testament to its universal and enduring value.

- Plato: Saw temperance as the harmony of the soul, where reason governs appetite and spirit. Essential for both individual justice and a just society.

- Aristotle: Positioned temperance as a mean between extremes, a rational habit formed through practice, crucial for achieving eudaimonia (human flourishing).

- The Stoics (e.g., Seneca, Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius): Valued temperance as a core component of living in accordance with nature and reason, essential for inner tranquility and resilience against external circumstances.

- Thomas Aquinas: Integrated temperance into Christian ethics, viewing it as a cardinal virtue that moderates the concupiscible appetites (desires for sensible goods), allowing reason to guide our pursuit of the good.

These varied perspectives, spanning centuries and philosophical traditions, converge on a central truth: temperance is indispensable for a well-lived life, a bulwark against the destructive potential of unbridled desire, and a pathway to genuine freedom through the strength of the Will.

Conclusion: The Enduring Wisdom of Temperate Living

In an age characterized by instant gratification and constant stimulation, the virtue of temperance offers a timeless antidote. It is a call to conscious living, to the deliberate exercise of our Will in navigating the powerful currents of desire. By understanding and cultivating temperance, we move beyond the simplistic binary of virtue and vice, embracing a nuanced approach that seeks not to deny our humanity, but to refine it. The wisdom of the ancients reminds us that true freedom and profound contentment are not found in the endless pursuit of external satisfactions, but in the internal harmony achieved when our reason gently, yet firmly, guides our appetites.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato Chariot Allegory Explained"

-

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics Temperance"