The Virtue of Temperance in Political Leadership: A bulwark Against Ruin

Summary: In the grand tapestry of political philosophy, few virtues are as foundational yet often overlooked as temperance. Far from mere abstinence, temperance in political leadership signifies a profound self-mastery, a judicious restraint over desires and passions, which is absolutely critical for stable government. Without it, leaders succumb to vice, leading to corruption, impulsivity, and the erosion of public trust. This article explores temperance through the lens of the Great Books of the Western World, demonstrating its intimate connection with prudence and its indispensable role in fostering just and enduring governance.

The Unseen Strength of Self-Restraint in Governance

When we envision ideal political leaders, we often focus on their courage, wisdom, or rhetorical prowess. Yet, beneath these more outwardly heroic qualities lies a quieter, more fundamental virtue: temperance. Temperance, derived from the Latin temperantia, meaning "moderation" or "self-control," is not simply about refraining from excess; it is about establishing the right measure, the harmonious balance that allows reason to guide action. For those entrusted with the immense power of government, this internal discipline is not a personal nicety but a societal necessity.

The history chronicled in the Great Books of the Western World is replete with examples of leaders whose downfall, and the subsequent suffering of their polities, can be directly attributed to a lack of temperance. Their unchecked appetites—for power, wealth, pleasure, or even unbridled ambition—transformed potential into catastrophe, showcasing the destructive interplay of virtue and vice in the public sphere.

Temperance: A Classical Perspective from the Great Books

The concept of temperance has deep roots in Western thought, often presented as a cornerstone of both individual well-being and a well-ordered society.

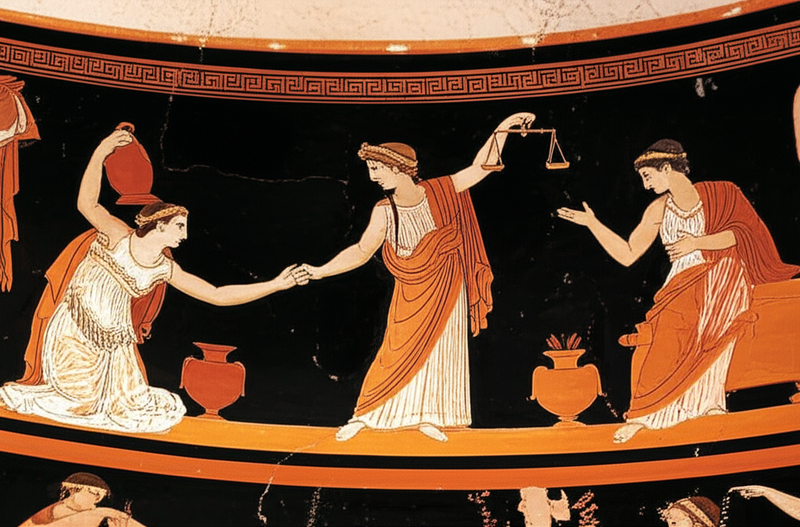

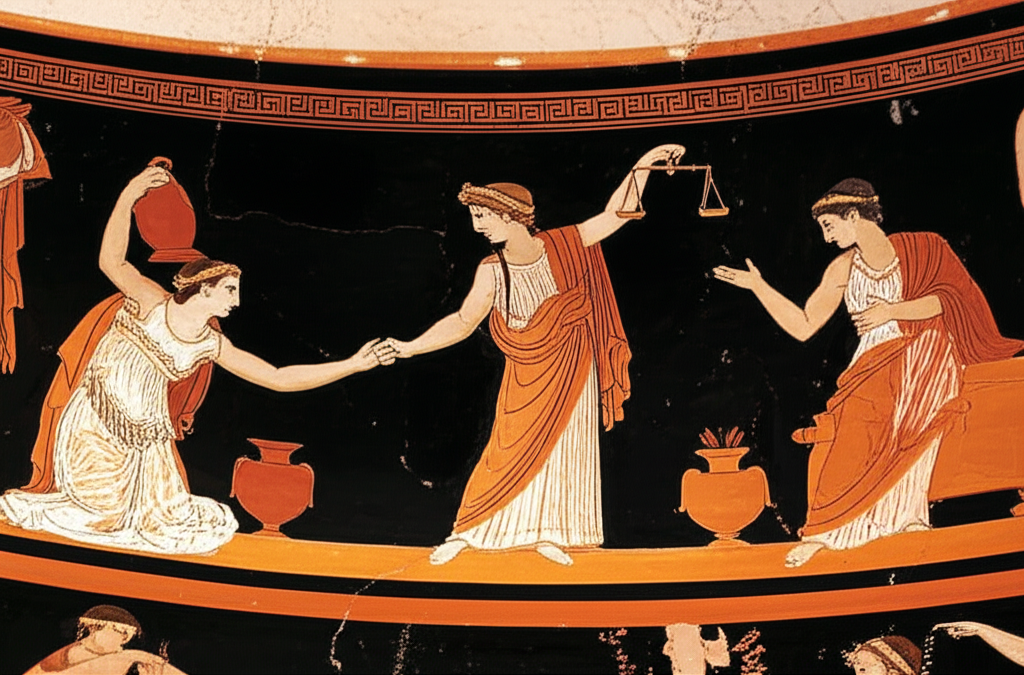

Plato's Vision of Harmony

In Plato's Republic, temperance (σφροσύνη, sophrosyne) is presented not merely as a personal virtue but as a state of internal harmony within the soul and, by extension, within the state. Plato likens the soul to a charioteer (reason) guiding two horses (spirit and appetite). Temperance is the agreement among these parts that reason should rule, ensuring that desires are kept in check. For the state, this means an alignment where all classes agree on who should govern, preventing the appetitive element (the masses) from overthrowing the rational (the philosopher-kings). A temperate government is one where order prevails from within, not merely through external coercion.

Aristotle's Doctrine of the Mean

Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, further refines temperance as a mean between two extremes:

- Excess: Licentiousness or self-indulgence, where one pursues pleasures without restraint.

- Deficiency: Insensibility or asceticism, where one is unduly indifferent to proper pleasures.

For Aristotle, a temperate person enjoys pleasures appropriately, neither too much nor too little, guided by prudence. This isn't about denying pleasure but about experiencing it in the right way, at the right time, and to the right degree. In leadership, this translates to using power, resources, and influence with judicious measure, avoiding both tyrannical overreach and debilitating passivity.

The Manifestation of Intemperance in Leadership

The absence of temperance often manifests in several destructive forms within political leadership, transforming potential strengths into crippling weaknesses.

| Aspect of Intemperance | Description | Impact on Government

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Virtue of Temperance in Political Leadership philosophy"