The Use of Dialectic in Defining Good and Evil

A Philosophical Compass for Moral Navigations

Summary: In the labyrinthine quest to grasp the essence of good and evil, philosophy has long grappled with the inadequacy of simple decrees. This article posits that the dialectic, as a rigorous method of intellectual inquiry, offers not a definitive answer, but an indispensable process for navigating and refining our understanding of these fundamental moral concepts. By challenging assumptions, exposing contradictions, and fostering synthesis, dialectic moves us beyond dogmatic pronouncements toward a more nuanced and robust definition of morality in a complex world.

The human condition is perpetually shadowed by the profound questions of good and evil. From the earliest myths to contemporary ethical dilemmas, we seek to understand what constitutes virtue and vice, right and wrong. Yet, the definition of these terms remains maddeningly elusive, shifting with cultural winds, personal perspectives, and historical epochs. How, then, can we hope to approach such monumental concepts with any hope of clarity? It is here, my dear reader, that we must turn to one of philosophy's most potent tools: the dialectic.

What is Dialectic? A Brief Philosophical Journey

At its core, dialectic is more than just a debate; it is a method of inquiry, a process of reasoning through contradictory ideas to arrive at a new understanding. Its lineage is ancient and distinguished, woven into the very fabric of Western thought.

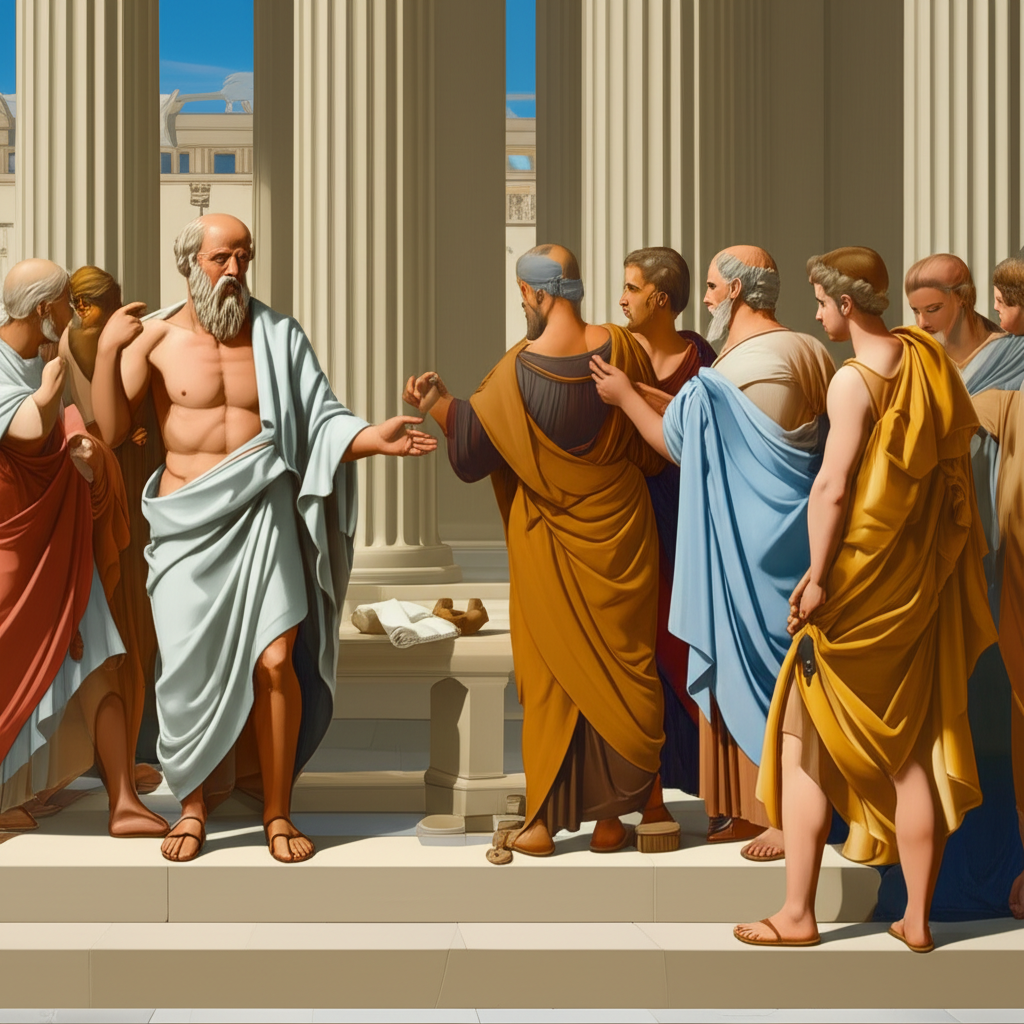

- Socratic Dialectic: Perhaps the most familiar form, as exemplified by Plato in the Great Books of the Western World. Socrates, through incisive questioning, would engage his interlocutors, challenging their initial assumptions (thesis) about concepts like justice or piety. By exposing the contradictions (antithesis) inherent in their beliefs, he aimed to lead them towards a more refined, if often elusive, truth (synthesis or aporia). This was less about winning an argument and more about purging ignorance and moving closer to genuine knowledge.

- Aristotelian Dialectic: In his Topics, Aristotle saw dialectic as the art of reasoning from generally accepted opinions (endoxa). While distinct from demonstrative science, it was crucial for examining probabilities and for the training of the mind to discern truth in matters where certainty was not attainable. It’s a method for testing propositions and exploring their implications.

- Hegelian Dialectic: Later, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel transformed dialectic into a grand historical process. For Hegel, reality and thought progress through a series of contradictions: a concept (thesis) generates its opposite (antithesis), and their tension is resolved in a higher, more comprehensive concept (synthesis). This synthesis then becomes a new thesis, perpetuating the cycle towards absolute knowledge. In this framework, even good and evil are understood as evolving concepts within the historical development of consciousness.

Regardless of its specific manifestation, the common thread is the confrontation of opposing ideas to forge a deeper, more comprehensive comprehension.

The Elusive Nature of Good and Evil

Why do good and evil resist straightforward definition? Consider the complexities:

- Cultural Relativism: What is considered good in one society (e.g., communal ownership) might be seen as antithetical to good in another (e.g., individual property rights).

- Individual Perspective: A decision that benefits one person might harm another, leading to conflicting moral assessments.

- Intent vs. Consequence: Is an act good if the intent was pure but the outcome disastrous? Or evil if the intent was malicious but the outcome accidentally beneficial?

- Divine Command vs. Natural Law: Is good simply what God commands, or are there inherent moral laws discoverable by reason, independent of divine decree?

Without a robust method, we risk either falling into moral relativism, where all definitions are equally valid (and thus none are), or into rigid dogmatism, where one’s own definition is imposed on all others, often with dire consequences.

Dialectic as a Tool for Moral Inquiry

This is precisely where dialectic shines. It provides a structured, critical approach to navigating the treacherous waters of moral definition.

- Challenging Assumptions: We often carry unexamined beliefs about good and evil inherited from culture, family, or religion. Dialectic forces us to articulate these beliefs (thesis) and then subject them to scrutiny. "Why do you consider this act good?" "What are the underlying principles of your definition?"

- Uncovering Contradictions: Through rigorous questioning, inconsistencies in our moral framework come to light (antithesis). Perhaps an act we label "good" in one context, when applied consistently, leads to an outcome we would universally condemn as "evil." This tension is not a failure, but an opportunity for growth.

- Towards Nuance and Synthesis: The goal is not to declare one side victorious, but to integrate the insights from both opposing viewpoints into a more sophisticated understanding. This synthetic understanding is richer, more robust, and more capable of addressing the complexities of real-world moral dilemmas. It acknowledges the multifaceted nature of good and evil, often revealing that what appears to be a clear dichotomy is, in fact, a spectrum of interwoven considerations.

Historical Applications from the Great Books

The Great Books of the Western World are replete with examples of dialectic being employed to define, or at least to grapple with, good and evil.

- Plato's Republic: Socrates' entire project in the Republic is a massive dialectical exercise to define justice, which is presented as the supreme good. He systematically examines and refutes various definitions of justice (e.g., Thrasymachus's "justice is the interest of the stronger") before proposing his own complex vision of a just soul and a just city. The dialogue unfolds through a constant back-and-forth, challenging assumptions and building arguments.

- Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics: While less overtly confrontational than Plato, Aristotle’s method is deeply dialectical. He begins by examining common opinions (endoxa) about happiness (eudaimonia – the ultimate good) and virtue, then systematically analyzes their strengths and weaknesses, refining concepts like courage, temperance, and justice through careful reasoning and empirical observation. His definition of virtue as a "mean between two extremes" is a product of this careful, often comparative, analysis.

- Augustine's Confessions: In his profound introspection, Augustine grapples with the definition of sin and the nature of evil, often through an internal dialectic. He recounts his own struggles, questioning his past actions and motivations, ultimately arriving at a theological understanding of evil as a privation of good, rather than a substance in itself. His arguments often involve wrestling with seemingly contradictory theological doctrines.

- Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit: Hegel's entire philosophy is structured around the dialectic. In his exploration of the master-slave dialectic, for instance, he shows how concepts of freedom, recognition, and self-consciousness (all related to human good) emerge through conflict and transformation. For Hegel, the definition of good and evil is not static but evolves with the historical unfolding of human spirit and its self-understanding.

The Ongoing Dialogue: Why Dialectic Remains Essential

In our increasingly interconnected and pluralistic world, the temptation to cling to simplistic, dogmatic definitions of good and evil is strong. Yet, it is precisely in such a world that dialectic becomes not just useful, but vital.

- It fosters intellectual humility, acknowledging that our initial understanding may be incomplete or flawed.

- It encourages empathy, as we are forced to engage with and understand perspectives that challenge our own.

- It promotes critical thinking, moving beyond superficial agreement or disagreement to explore the underlying logic and implications of moral claims.

The dialectic does not promise a final, universally accepted definition of good and evil—perhaps such a thing is beyond human grasp. Instead, it offers a dynamic, ongoing process of inquiry that refines our understanding, broadens our perspective, and equips us to navigate the perennial moral challenges of existence with greater wisdom and discernment. It is a journey, not a destination, and one that every serious student of philosophy must undertake.

YouTube:

- "Plato's Dialectic Explained"

- "Hegel's Dialectic: Understanding Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Use of Dialectic in Defining Good and Evil philosophy"