The Art of Persuasion: Unpacking Analogy's Role in Philosophical Reasoning

Analogy, often seen as a mere rhetorical flourish, stands as a cornerstone in the edifice of philosophical reasoning. From the ancient Greeks to contemporary thought, philosophers have leveraged the power of comparison to illuminate complex ideas, forge new connections, and persuade minds. This article delves into the profound, yet often perilous, use of analogy in philosophy, exploring its historical roots, its structural logic, and the critical discernment required to wield it effectively. We will examine how the identification of a shared relation between disparate concepts can unlock profound insights, while also cautioning against the pitfalls of misplaced or overextended comparisons.

What is Analogy in Philosophical Context?

At its core, an analogy is a comparison between two objects or systems of objects that highlights respects in which they are thought to be similar. In philosophical reasoning, however, it transcends simple likeness. It is a method of inference where, if two or more things are similar in some known respects, they are also likely to be similar in other respects. This isn't merely about superficial resemblance but about identifying a deeper structural or functional relation.

Unlike a metaphor, which asserts that A is B to create a vivid image, or a simile, which states A is like B, an analogy often argues that the relation between elements in one scenario is parallel to the relation between elements in another. For instance, the relation of a captain to a ship might be analogous to the relation of a ruler to a state. Philosophers turn to analogy when direct demonstration is elusive, when abstract concepts need grounding, or when they seek to extend understanding from the familiar to the unfamiliar. It serves as a powerful tool for conceptual exploration and the construction of arguments, providing a scaffold for logic where intuition might otherwise falter.

The Historical Tapestry of Analogical Reasoning

The history of philosophy is replete with iconic analogies that have shaped our understanding of reality, knowledge, and ethics. From the dialogues of Plato to the systematic treatises of Aristotle, and through the rigorous theological arguments of the medieval period, analogy has been an indispensable instrument of thought.

Key Philosophers and Their Enduring Analogies

| Philosopher | Notable Analogy | Purpose and Philosophical Significance |

|---|---|---|

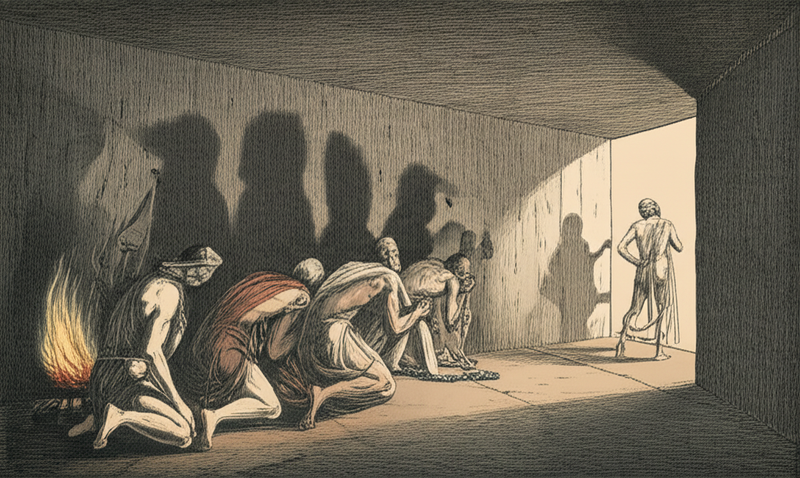

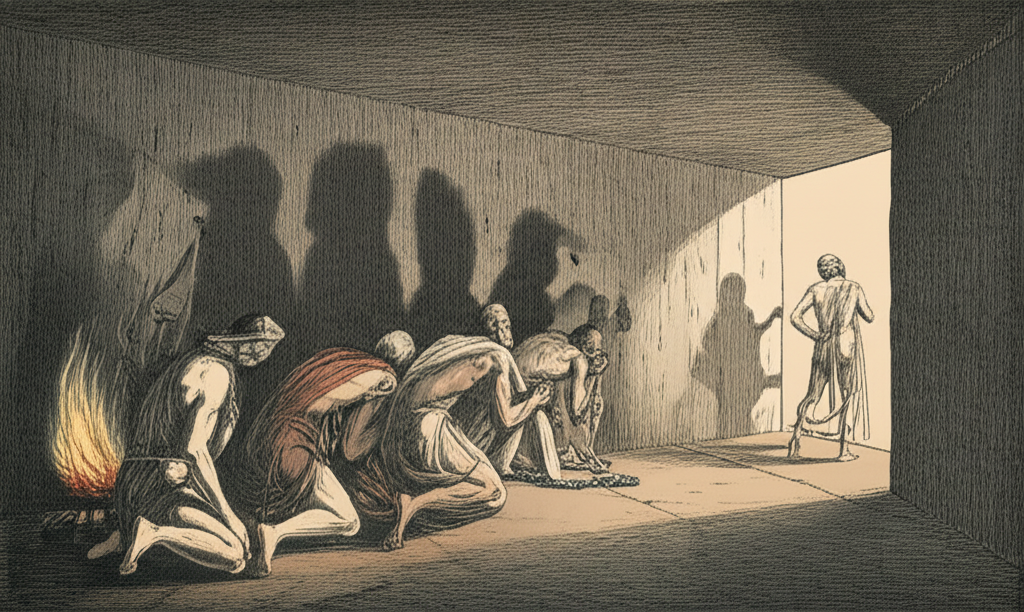

| Plato | Allegory of the Cave | Illustrates the journey from ignorance to knowledge, the nature of reality (Forms), and the philosopher's role in enlightenment. |

| Ship of State | Compares the governance of a state to the navigation of a ship, emphasizing the need for skilled, wise leadership (philosopher-kings). | |

| Aristotle | Analogy of Being | Used to explain how "being" is predicated in various ways (substance, quality, quantity) but always relates back to substance. |

| Thomas Aquinas | Analogy of Being/Proportion | Applied to understand the attributes of God by drawing comparisons from created things, recognizing that divine perfections are similar yet infinitely superior. |

| René Descartes | Wax Analogy | In Meditations, uses a piece of wax to demonstrate that true knowledge of objects comes from the intellect, not just the senses, highlighting the mind's role in reasoning. |

| John Locke | Tabula Rasa | Compares the mind at birth to a blank slate, arguing that all knowledge derives from experience. |

These examples underscore how philosophers, across millennia, have relied on the intuitive appeal of analogy to bridge conceptual gaps and to articulate profound truths about human experience and the cosmos. The identification of a crucial relation between the elements of the analogy is what gives it its persuasive force.

The Mechanics of Analogical Argumentation

An analogical argument typically follows a structure where one observes that two or more entities (A and B) are similar in certain known respects (P, Q, R). From this observed similarity, one infers that they are also likely to be similar in some further respect (S) that is known to hold for A but not yet for B.

The logic of such an argument relies heavily on the strength of the relation between the compared properties. Consider the structure:

- A has properties P, Q, R.

- B has properties P, Q, R.

- A also has property S.

- Therefore, B probably has property S.

The effectiveness of this reasoning hinges on several factors:

- Relevance of Similarities: Are the shared properties (P, Q, R) genuinely relevant to the inferred property (S)? If we compare a human brain to a computer, the shared relation of processing information is relevant, but the physical composition is largely irrelevant to the analogy's cognitive claims.

- Number of Similarities: Generally, the more relevant similarities, the stronger the analogy.

- Number of Dissimilarities: Conversely, significant dissimilarities, especially if relevant to S, weaken the argument.

- Diversity of Cases: If the analogy is drawn from a diverse set of cases, it can be stronger.

Analogical arguments are generally considered inductive rather than deductive. They offer probable conclusions, not certain ones. The logic is not about deriving a truth from premises but about extending a pattern of reasoning from one domain to another.

The Power and Peril of Analogical Reasoning

The use of analogy in philosophy is a double-edged sword, offering both immense potential for insight and significant risks of misdirection.

The Power of Analogy

- Clarity and Comprehension: Analogies make abstract and complex philosophical concepts accessible. By relating the unknown to the known, they facilitate understanding and provide a framework for grasping difficult ideas. Plato's Cave, for example, makes the theory of Forms intuitively graspable.

- Heuristic Function: Analogies are powerful tools for discovery and hypothesis generation. They can suggest new avenues of inquiry, help formulate new theories, and expose previously unnoticed relations between phenomena. Much scientific reasoning begins with analogical insights.

- Persuasion and Rhetoric: A well-chosen analogy can be incredibly persuasive, imbuing an argument with vividness and emotional resonance. It can make a philosophical position seem intuitively correct, fostering acceptance even before rigorous logic is fully unpacked.

The Peril of Analogy

- Misleading Comparisons (False Equivalences): The greatest danger lies in the assumption that because two things are similar in some respects, they are similar in all or the most crucial respects. A false analogy can create a superficial resemblance that masks fundamental differences, leading to erroneous conclusions. For instance, comparing the state to a family might neglect the distinct relations of power and consent involved.

- Overextension: Taking an analogy too far, extending it beyond its legitimate points of comparison, is another common pitfall. While a brain might be like a computer in processing information, it is not literally a computer, and drawing conclusions about consciousness based solely on computer operations can be problematic.

- Begging the Question: Sometimes, an analogy assumes the very point it is trying to prove. If the relation being argued for is already implicitly accepted within the analogy, it fails to provide independent reasoning.

- Distraction from Core Arguments: A compelling analogy can sometimes distract from the need for rigorous, non-analogical logic and evidence, leading to arguments that are more poetic than sound.

Contemporary Perspectives and Critical Analysis

In modern philosophy, while the heuristic and explanatory power of analogy is still acknowledged, there's a heightened awareness of its limitations. Contemporary philosophers often employ analogies as starting points for thought experiments or as illustrative devices, but rarely as the sole foundation for a robust argument. The emphasis is on critically examining the relation being drawn and scrutinizing whether the similarities outweigh the differences in the context of the specific philosophical claim.

For example, ethical dilemmas often utilize analogies to highlight moral consistency or inconsistency. If we agree that X is wrong in scenario A, an analogy might argue that Y, which shares crucial moral relations with X, must also be wrong in scenario B. However, the critical task is always to identify if those "crucial moral relations" truly hold and are not overshadowed by other morally relevant differences. The careful application of logic and a deep understanding of the concepts involved are paramount when engaging with analogical reasoning.

Conclusion

The use of analogy in philosophical reasoning is a testament to the human mind's innate drive to find patterns, make connections, and understand the world through comparison. From the profound insights of Plato's Allegory of the Cave to the intricate logic of Aquinas's analogy of being, it has served as an invaluable tool for conceptual clarification, discovery, and persuasion. Yet, as with any powerful instrument, its deployment demands careful consideration and critical discernment. While analogies can brilliantly illuminate the shared relation between disparate ideas, their seductive simplicity must always be tempered by rigorous reasoning to avoid the pitfalls of false equivalences and overextension. Ultimately, the judicious philosopher understands that analogy is a guide to understanding, not an unassailable proof in itself, requiring constant scrutiny to ensure its insights are genuinely profound and not merely superficially appealing.

**## 📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Allegory of the Cave Explained""**

**## 📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Analogical Reasoning in Philosophy and Logic""**