The Enduring Utility of Analogy in Philosophical Reasoning

Analogy, far from being a mere rhetorical flourish, stands as a fundamental instrument in the philosopher's toolkit, providing a unique pathway for reasoning through the intricate landscapes of abstract thought. This article explores the vital role of analogy in philosophy, examining how it illuminates complex concepts, guides logical inquiry, and establishes crucial relations between disparate ideas. We will delve into its structure, its power, and its inherent limitations, drawing upon examples from the rich tradition of the Great Books of the Western World to demonstrate its profound and enduring utility.

Unpacking the Philosophical Analogy

At its core, an analogy in philosophy is more than a simple comparison; it is a profound act of discerning a relation of relations. It operates by identifying a structural or functional similarity between two domains – one familiar (the source) and one less understood (the target) – to infer further similarities. This process is not about asserting identity but about highlighting proportional correspondence, allowing us to project insights from the known onto the unknown. It is a powerful method of reasoning that helps bridge the gap between empirical observation and metaphysical speculation.

Why Analogy Matters in Philosophical Inquiry

The human intellect often grapples with concepts that defy direct empirical observation, such as justice, consciousness, or the nature of being. Analogy offers a conceptual ladder, enabling us to grasp these abstract notions by relating them to more concrete or familiar experiences.

- Illumination: Analogies can make abstract ideas palpable, turning opaque concepts into understandable constructs.

- Hypothesis Generation: They serve as fertile ground for developing new theories and thought experiments, guiding our reasoning towards novel conclusions.

- Argumentation: While not a proof in itself, a well-crafted analogy can significantly strengthen an argument by demonstrating the plausibility or coherence of a philosophical position.

- Conceptual Clarification: By mapping structures from one domain to another, analogies force us to articulate the precise relations we perceive, thereby refining our understanding.

The Logic and Limits of Analogical Reasoning

While immensely beneficial, analogical reasoning is a delicate art, demanding careful application. Its strength lies in its capacity to suggest and persuade, but its conclusions are only as robust as the underlying relation it posits.

Constructing a Sound Analogy

A compelling philosophical analogy typically involves:

- A Clear Source Domain: A subject or situation that is well-understood and provides the basis for comparison.

- A Defined Target Domain: The subject or situation that is less understood, which the analogy aims to illuminate.

- Identified Similarities (Positive Analogy): The characteristics or relations explicitly shared between the source and target.

- Identified Differences (Negative Analogy): The characteristics or relations known to be not shared, which are crucial for understanding the analogy's boundaries.

- Inferred Similarities (Neutral Analogy): The characteristics or relations in the target domain that are hypothesized based on the similarities in the source domain.

| Component | Description | Example (Plato's Ship of State) |

|---|---|---|

| Source Domain | A ship and its crew. | A ship, its owner, its crew, the navigator. |

| Target Domain | A state and its governance. | A state, its citizens, politicians, the philosopher-king. |

| Positive Analogy | Both require skilled leadership; both face dangers (storms/anarchy). | The ship needs a navigator to reach its destination; the state needs a wise ruler for justice. |

| Negative Analogy | A ship has a physical destination; a state's 'destination' is more abstract. | A ship's journey is finite; a state's existence is ideally continuous. |

| Inferred Similarities | Just as a ship needs a wise navigator, a state needs a wise ruler. | The true ruler (philosopher-king) possesses the knowledge of navigation (justice). |

The Pitfalls of Misguided Analogies

Despite its power, analogy is not without its perils. Superficial similarities, overlooked differences, or overextension of the comparison can lead to flawed reasoning. A common fallacy is the "false analogy," where the relation between the source and target domains is too weak or irrelevant to support the intended inference. It is crucial to remember that analogies serve to illustrate and explore, not to definitively prove.

Illustrious Examples from the Great Books

The history of philosophy is replete with iconic analogies that have shaped our understanding and fueled centuries of reasoning.

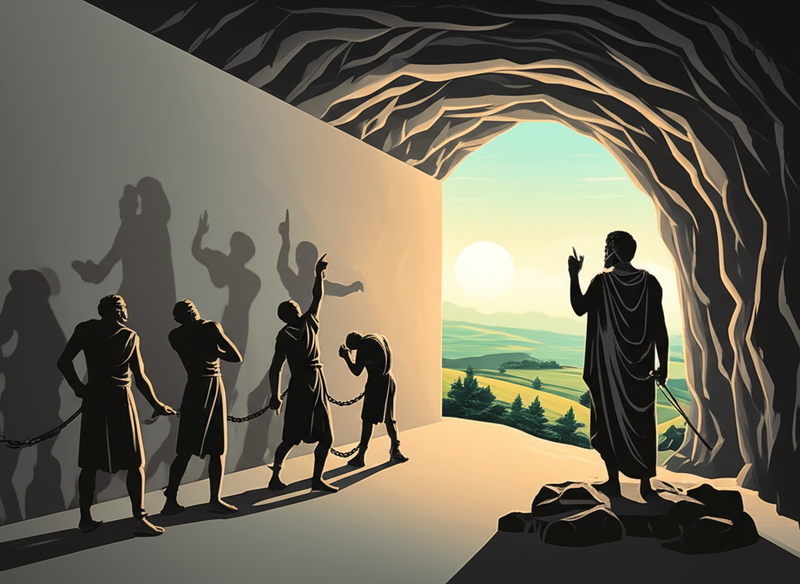

- Plato's Cave (from The Republic): Perhaps the most famous, this analogy powerfully illustrates the journey from ignorance to enlightenment, the nature of reality, and the philosopher's role in society. The shadows on the cave wall bear a distinct relation to our perceived reality, much like the Forms bear a relation to true knowledge.

- Aristotle's Organic State (from Politics): Aristotle often drew analogies between the state and a living organism. Just as an organism's parts (organs) serve specific functions for the health of the whole, so too do citizens and institutions contribute to the flourishing of the polis. This biological relation informed his functionalist approach to political philosophy.

- Aquinas's Analogical Predication (from Summa Theologica): When speaking of God, Aquinas argued that terms like "good" or "wise" are not used univocally (in the exact same sense as when applied to humans) nor equivocally (in entirely different senses), but analogically. There is a relation of proportion: God is good in a way that is proportional to His infinite nature, just as humans are good in a way proportional to their finite nature. This allowed for meaningful theological reasoning without anthropomorphizing the divine.

- Descartes' Wax Argument (from Meditations on First Philosophy): While not a direct analogy in the sense of comparing two distinct domains, Descartes uses the example of a piece of wax to illustrate how our understanding of its essence (its extension, flexibility, changeability) comes from the mind's pure reasoning, not merely from sensory perception. The wax's changing forms relate to how our intellectual apprehension remains constant despite sensory flux.

Conclusion: The Indispensable Guide to Philosophical Understanding

The use of analogy in philosophical reasoning is a testament to the human mind's capacity to find patterns, discern relations, and extend understanding beyond immediate experience. From the foundational myths of Plato to the intricate theological arguments of Aquinas, analogies have served as indispensable tools for making the abstract concrete, the complex comprehensible, and the unknown approachable. While demanding careful construction and critical evaluation, the judicious application of analogy remains a cornerstone of profound philosophical inquiry, guiding our logic and enriching our pursuit of wisdom.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Allegory of the Cave explained""

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Analogy in Philosophy: Strengths and Weaknesses""