The State of Nature Hypothesis is a cornerstone of political philosophy, a powerful thought experiment designed to illuminate the fundamental questions surrounding human society, morality, and the necessity of Government. It asks: What would life be like without any form of organized society, laws, or a sovereign power? By imagining humanity in this primordial, pre-political State, philosophers from the "Great Books of the Western World" tradition sought to justify, critique, and understand the very foundations of the State itself, revealing profound insights into human Nature and the social contract.

The Primitive Condition: Unpacking the State of Nature

At its core, the State of Nature Hypothesis is an intellectual device, not a historical claim. It's a conceptual baseline from which to analyze the merits and drawbacks of political authority. Before the emergence of the State, of laws, of justice as we understand it, what governs human interaction? Is it reason, self-interest, fear, or benevolence? The answers to these questions profoundly shape a philosopher's view on the ideal form and scope of Government.

Philosophers like Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose works are foundational to Western thought, each offered distinct and often contradictory visions of this hypothetical pre-social existence, providing a rich tapestry of perspectives on human Nature and the origins of political power.

Architects of the Hypothesis: Diverse Visions of Primitive Humanity

The "Great Books" tradition offers us three particularly influential interpretations of the State of Nature, each leading to a unique justification for the State and Government.

Thomas Hobbes: A War of All Against All

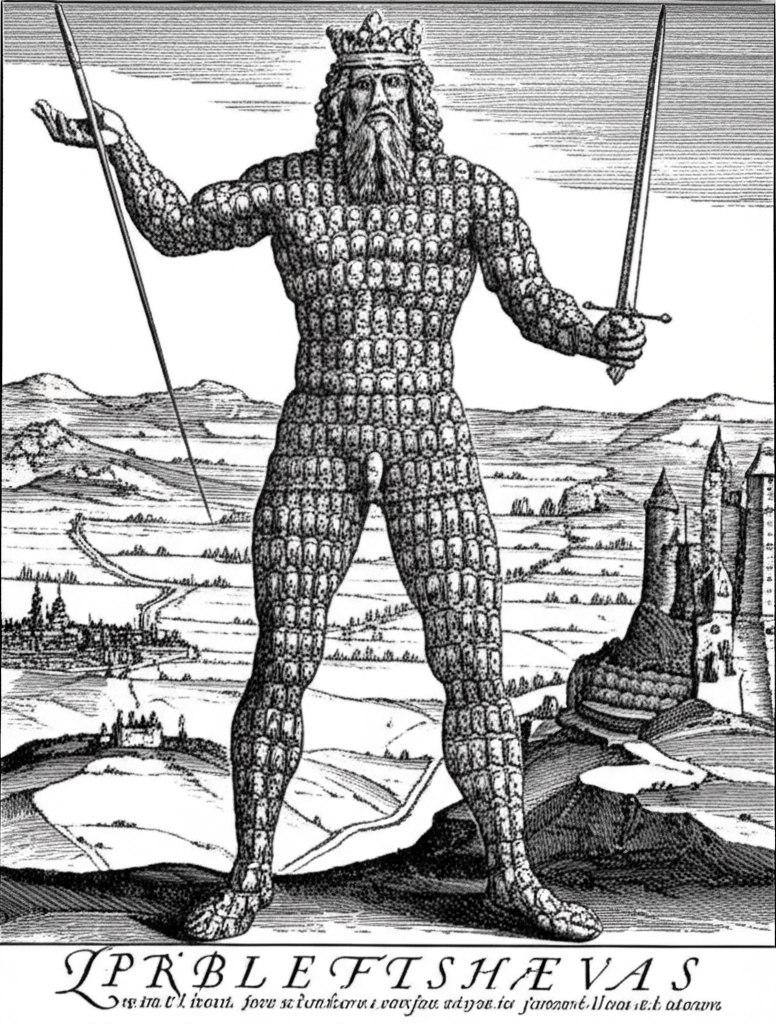

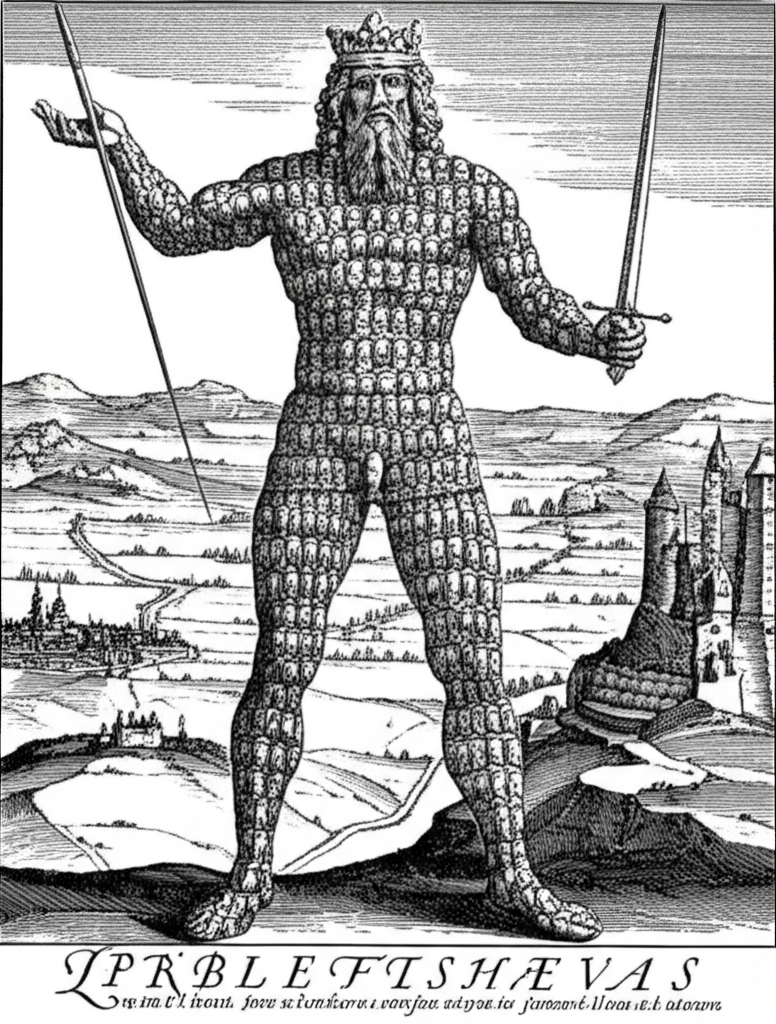

For Thomas Hobbes, articulated powerfully in his Leviathan, the State of Nature is a grim and terrifying prospect. He posited that without a common power to hold them in awe, humans, driven by self-preservation and a perpetual fear of death, would inevitably descend into a "war of every man against every man" (bellum omnium contra omnes). In this State, there is no industry, no culture, no society; life is "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short."

Hobbes’s Hypothesis suggests that human Nature, left unchecked, is fundamentally egoistic and competitive. The only escape from this chaotic existence is through a social contract where individuals surrender some of their absolute freedom to an all-powerful sovereign—the State—capable of enforcing laws and maintaining order. For Hobbes, the absolute Government is not merely preferable, but an existential necessity.

John Locke: Reason, Rights, and Inconvenience

John Locke, in his Two Treatises of Government, presents a far more optimistic view of the State of Nature. Unlike Hobbes, Locke believed that even in the absence of a formal Government, humanity is governed by a Law of Nature, discoverable by reason. This law dictates that all individuals are equal and possess inherent natural rights to life, liberty, and property.

While not a State of war, Locke's State of Nature is still inconvenient. Without an impartial judge, common laws, or an executive power to enforce them, disputes are likely to arise, and individuals would be left to protect their own rights, often leading to partiality and instability. Thus, the primary purpose of forming a Government (the State) is not to escape utter chaos, but to better protect these pre-existing natural rights and provide for their impartial enforcement. Locke’s vision champions limited Government by consent, safeguarding individual freedoms rather than suppressing them entirely.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau: The Noble Savage and Social Corruption

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, particularly in his Discourse on Inequality and The Social Contract, offers a radical departure from both Hobbes and Locke. For Rousseau, the original State of Nature was a peaceful, idyllic condition where humans were "noble savages"—solitary, self-sufficient, and guided by instinct and natural pity, not by reason or moral concepts. They were free and uncorrupted.

It was the advent of private property, agriculture, and the formation of society that introduced inequality, competition, and moral corruption, leading to conflict and the need for a Government. Rousseau argued that the first forms of Government were often a trick by the powerful to cement their advantages. His ideal State, therefore, aims to restore a form of freedom and equality through a social contract based on the "general will," where citizens collectively legislate for the common good, thereby preserving a semblance of their original liberty.

The Enduring Purpose of the Hypothesis: Justifying the State

Why engage in such abstract thought experiments? The State of Nature Hypothesis serves several crucial functions in political philosophy:

- Legitimacy of Government: It provides a framework for understanding why we need a Government and what its legitimate functions are. Is it to prevent utter destruction (Hobbes), protect rights (Locke), or restore lost freedom (Rousseau)?

- Human Nature: It forces us to confront our assumptions about human Nature. Are we inherently good, evil, or amoral? The answer profoundly impacts our political philosophy.

- Rights and Obligations: By imagining a world without laws, it helps define which rights are natural and which are products of society, and what reciprocal obligations individuals have to each other and to the State.

- Critique of Existing Systems: By comparing the imagined State of Nature with existing political realities, philosophers can critique contemporary governments and advocate for reform.

Beyond the Hypothetical: Modern Echoes and Criticisms

While the State of Nature Hypothesis is a conceptual tool, its implications resonate deeply in modern political thought. We see echoes of it in discussions about international relations (where nations might be seen as existing in a global State of Nature), the ethics of failed states, or debates about fundamental human rights that transcend national borders.

Critics argue that the Hypothesis is ahistorical, overly simplistic in its view of human Nature, and potentially misleading. No society has ever existed entirely without some form of social norms or hierarchies. Yet, its enduring power lies not in its historical accuracy, but in its ability to strip away the layers of convention and force us to ask fundamental questions about power, justice, and the very essence of human community.

Conclusion: An Enduring Legacy

The State of Nature Hypothesis remains an indispensable concept for anyone delving into political philosophy. From the war-torn landscape of Hobbes to Locke's reasoned society and Rousseau's noble wilderness, these varied interpretations from the "Great Books" tradition offer profound insights into the human condition and the enduring quest for legitimate Government. It compels us to consider not just what the State is, but why it exists, and what fundamental aspects of our Nature it seeks to address or transform.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Hobbes Locke Rousseau State of Nature Comparison"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Political Philosophy The Social Contract Explained"