The Untamed Mind: Unpacking the State of Nature Hypothesis

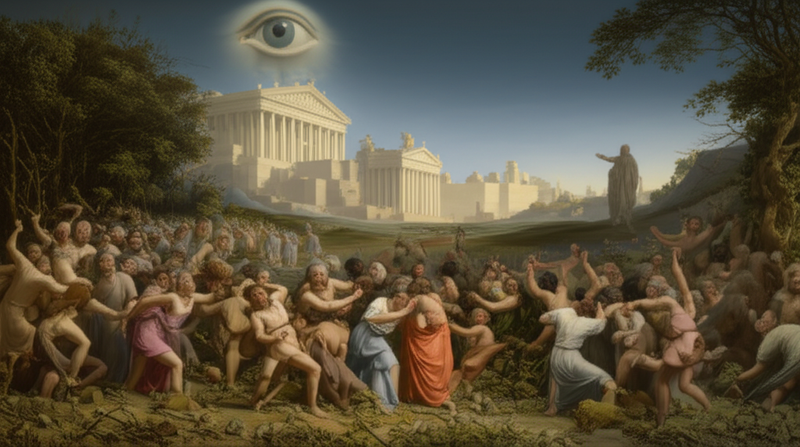

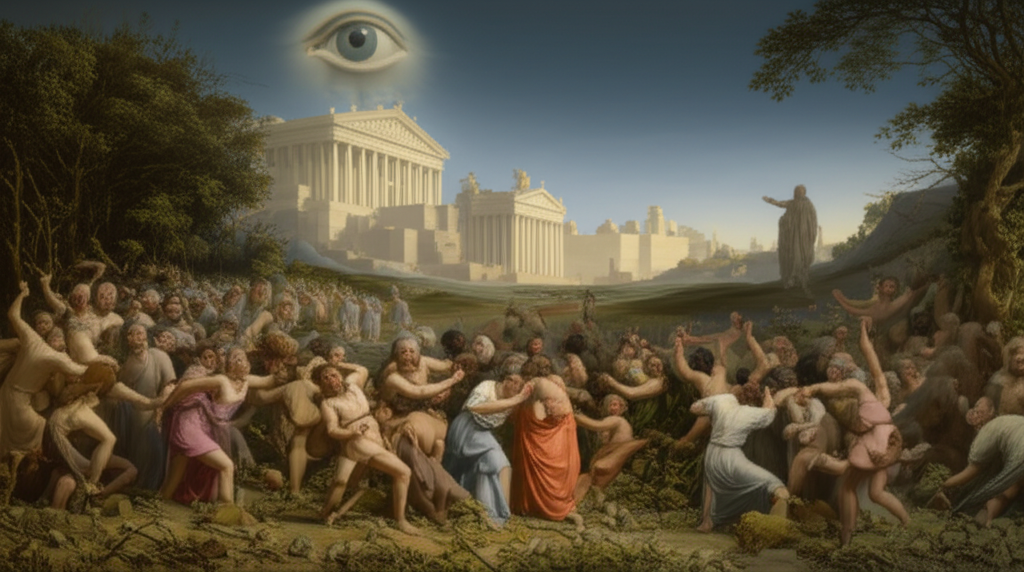

Have you ever stopped to truly consider what life would be like without the intricate web of rules, laws, and institutions that govern our daily existence? Strip away the police, the courts, the political parties, even the unspoken social contracts that dictate our interactions. What remains? This profound question lies at the heart of one of political philosophy's most enduring and illuminating thought experiments: The State of Nature Hypothesis.

At its core, the State of Nature Hypothesis is a conceptual tool, a philosophical construct used to explore the fundamental characteristics of human nature and the theoretical reasons for the formation of government and organized society. It posits a hypothetical pre-political condition where no established authority or civil law exists. By imagining humanity in this raw, unadulterated state, philosophers seek to understand the origins of societal structures, the justification for political power, and the inherent rights and duties of individuals. It's not a historical account, but rather a powerful analytical lens through which we examine the very foundations of our collective life.

Imagining the Unburdened Human: Divergent Views on Our Primal State

The beauty, and indeed the enduring fascination, of the State of Nature Hypothesis lies in the starkly different conclusions drawn by some of the greatest minds in Western thought. These varied interpretations, often found within the pages of the Great Books of the Western World, offer profound insights into the human condition and the necessity of the State.

1. Thomas Hobbes: The War of All Against All

For Thomas Hobbes, writing in his seminal work Leviathan, the State of Nature is a grim and terrifying prospect. He famously described human life in this condition as "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short."

- Human Nature: According to Hobbes, humans are fundamentally self-interested and driven by a desire for power. In the absence of a common power to keep them in awe, individuals are constantly in a state of fear and competition.

- The Outcome: Without laws or enforcement, every individual has a right to everything, leading to a perpetual "war of every man against every man" (bellum omnium contra omnes). There is no industry, no culture, no society, only constant strife and the threat of violent death.

- The Solution (Government): To escape this intolerable state, rational individuals would willingly surrender some of their absolute freedom to a powerful, absolute sovereign – a government – in exchange for security and order. This social contract forms the basis of the State.

2. John Locke: Natural Rights and Inconveniences

John Locke, in his Two Treatises of Government, presented a far more optimistic vision of the State of Nature. While acknowledging its imperfections, he believed it was governed by a Law of Nature, discoverable by reason.

- Human Nature: Locke posited that humans are born with inherent natural rights: life, liberty, and property. They are also capable of reason and moral judgment, understanding that they should not harm others in their life, health, liberty, or possessions.

- The Outcome: The State of Nature is not necessarily a state of war, but rather one of "peace, goodwill, mutual assistance, and preservation." However, it suffers from "inconveniences." Without a common judge, disputes over natural rights can escalate, and there's no guaranteed enforcement of justice.

- The Solution (Government): People form a government not to escape utter chaos, but to better protect their pre-existing natural rights. The government's legitimacy derives from the consent of the governed, and its primary purpose is to uphold the Law of Nature and secure individual liberties.

3. Jean-Jacques Rousseau: The Noble Savage and Social Corruption

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, particularly in his Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (Second Discourse), offered a radical counter-narrative, suggesting that civilization, not the State of Nature, was the source of human corruption.

- Human Nature: Rousseau imagined humans in the primordial state as "noble savages" – solitary, self-sufficient beings driven by self-preservation (amour de soi) and pity (pitié). They are naturally good, free, and uncorrupted by societal vices.

- The Outcome: The original State of Nature was a peaceful, if primitive, existence. It was the introduction of private property, agriculture, and the subsequent development of society, competition, and inequality that led to moral decay, conflict, and the loss of natural freedom.

- The Solution (Government): Rousseau's ideal government (as explored in The Social Contract) aims to restore a form of collective freedom and equality, guided by the "general will," rather than simply protecting individual rights against a chaotic state of nature.

Image:

Why Does This Hypothesis Still Matter?

The State of Nature Hypothesis, despite its varied interpretations, remains a cornerstone of political philosophy for several crucial reasons:

- Justifying Government: It provides a powerful framework for understanding why we have government at all. Is it a necessary evil, a protector of rights, or a corrupting influence?

- Defining Human Nature: The different hypotheses force us to confront our own assumptions about human nature. Are we inherently good, selfish, or malleable?

- Legitimacy and Authority: By imagining a world without rules, we can better analyze the legitimacy of existing rules and the authority of our current government. What makes a state just? What are our obligations to it?

- Social Contract Theory: The State of Nature is the starting point for most social contract theories, exploring the implicit or explicit agreement by which individuals form societies and empower governments.

A Table of Contrasts: The State of Nature in Summary

| Philosopher | Core View of Human Nature | Description of the State of Nature | Reason for Government | Ideal Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hobbes | Self-interested, power-seeking | "War of all against all"; solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, short | Escape violent death and chaos; ensure security | Absolute Sovereign |

| Locke | Rational, possessing natural rights | Governed by Law of Nature; mostly peaceful but inconvenient | Protect natural rights (life, liberty, property); provide common judge | Limited, Constitutional |

| Rousseau | Naturally good, free, compassionate | Peaceful, primitive, innocent; society corrupts | Restore collective freedom and equality; express general will | Direct Democracy (General Will) |

In contemplating the State of Nature Hypothesis, we are not merely engaging in an abstract academic exercise. We are, in fact, holding a mirror to our own society, questioning its foundations, and reflecting on the very essence of what it means to be human in a collective state. It compels us to ask: What would we truly lose, or gain, without the structures we often take for granted? And what, then, is the true purpose and ideal form of our government?

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Hobbes Locke Rousseau State of Nature Explained"

2. ## 📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Political Philosophy The Social Contract Theory"