The Unyielding Command: Exploring the Role of Will in Moral Action and Duty

The will stands as the cornerstone of our moral universe, serving as the essential faculty through which we apprehend, internalize, and execute our duties. This article delves into the profound connection between a rational will and moral action, particularly through the lens of duty, examining how our capacity for choice and intention shapes our understanding and pursuit of Good while navigating the complexities of Evil.

Introduction: The Inner Compulsion to Act Rightly

As Chloe Fitzgerald, I often find myself pondering the invisible forces that compel us to act. What is it that truly drives our moral choices? Is it an an external decree, a societal pressure, or something far more intrinsic? For many of the great thinkers whose works fill the "Great Books of the Western World," the answer lies squarely with the will. It is not merely a desire or an inclination, but a profound faculty that bridges our inner world of reason and our outer world of action, shaping our understanding of duty and distinguishing between Good and Evil.

The concept of will is not monolithic; it has been debated and defined across millennia. Yet, in the context of moral action, it consistently emerges as the primary agent of our ethical lives. Without a will capable of choosing, deliberating, and executing, the very notion of moral responsibility would crumble.

The Will's Command: Duty and the Categorical Imperative

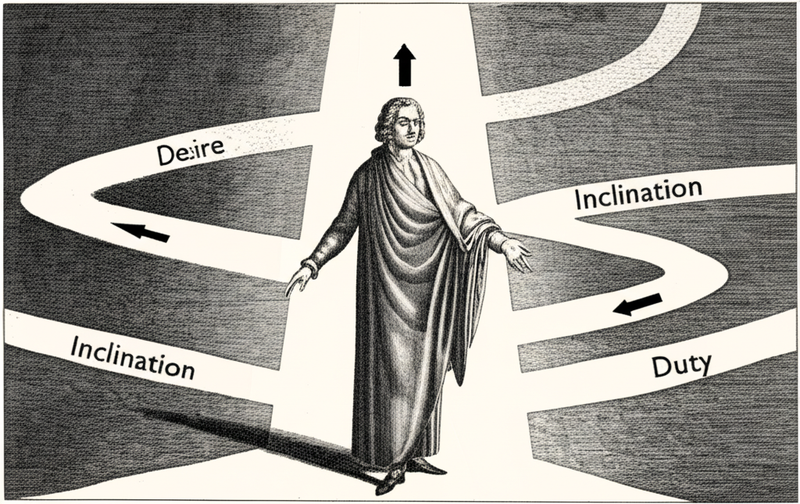

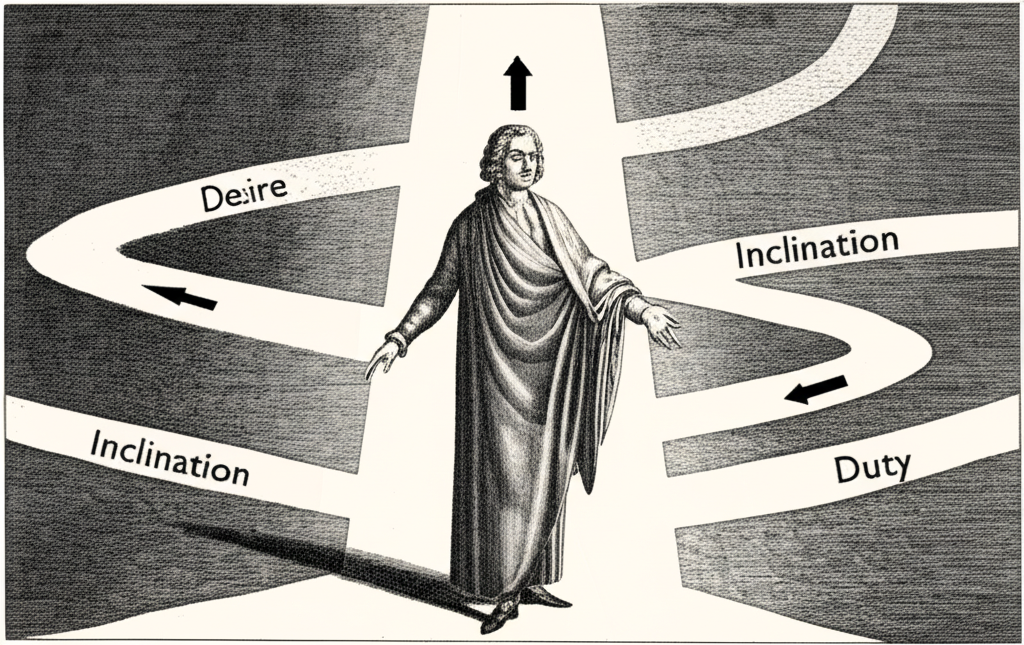

Perhaps no philosopher articulated the role of the will in moral action more rigorously than Immanuel Kant. For Kant, a truly moral action is not one driven by inclination, sentiment, or even a desired outcome, but by duty. And this duty, this moral law, is something that the rational will prescribes to itself.

-

The Good Will: Unqualified Goodness

Kant famously asserted in his Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals that "It is impossible to conceive of anything at all in the world, or even out of it, which can be taken to be good without qualification, except a good will." This is a radical claim. Talents, power, wealth – all can be used for evil purposes. But a will that acts from duty, out of respect for the moral law, is inherently Good. -

Duty as Necessity: Beyond Inclination

For Kant, acting from duty means doing something because it is the right thing to do, not because of what it might achieve for us. If I help someone because I feel sympathy, my action is commendable, but not strictly moral in the Kantian sense. If I help them because my rational will recognizes a duty to do so, irrespective of my feelings, then my action possesses true moral worth.Consider the following distinction:

Basis of Action Moral Worth (Kantian Perspective) Inclination Contingent, not truly moral (e.g., sympathy, self-interest) Duty Possesses true moral worth (e.g., respect for moral law) This highlights the will's critical role in elevating an action from mere desire to moral imperative.

Navigating Good and Evil: The Will's Moral Compass

How does the will distinguish between Good and Evil? This is where the rational aspect of the will becomes paramount. It's not about what feels good, or what brings the most pleasure, but what can be consistently willed as a universal law.

-

The Categorical Imperative: A Test for the Will

Kant's Categorical Imperative provides a framework for the will to test the morality of its proposed actions. One formulation states: "Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law." If your will cannot consistently universalize an action (e.g., "I will lie whenever it suits me"), then that action is immoral. The will, therefore, acts as a legislator, determining what is permissible for all rational beings. -

Intention vs. Consequence: Where Goodness Resides

The will's intention is central. An action might have negative consequences despite a Good intention, or positive consequences despite an Evil one. For Kant, the moral value resides in the will that prompts the action, in its adherence to duty, not in the often unpredictable outcomes. This places an immense role on the inner workings of our moral faculty.- The Will's Struggle: The moral life is often a struggle between our rational will and our various inclinations (desires, fears, emotions). The duty of a moral agent is to ensure that the will triumphs over these inclinations when they conflict with the moral law.

Historical Echoes: The Will Across the Great Books

While Kant provided a definitive framework for will and duty, the question of the will's role has resonated through centuries of philosophical inquiry, woven into the fabric of the "Great Books of the Western World."

-

Plato's Tripartite Soul: Reason's Command

In Plato's Republic, the soul is divided into three parts: reason, spirit, and appetite. While not explicitly "will," Plato emphasizes the role of reason in governing the other parts. A just individual is one whose reason (akin to a rational will) directs the spirited and appetitive parts, aligning them towards Good. -

Aristotle's Deliberate Choice (Prohairesis):

Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, speaks of prohairesis, often translated as "deliberate choice" or "moral choice." This is a choice that results from deliberation and is directed towards an end. While distinct from Kant's duty-based will, it highlights the role of a rational faculty in choosing actions that lead to Good (virtue and eudaimonia). It underscores that moral action isn't accidental but flows from a considered, willed decision. -

Augustine's Free Will and the Origin of Evil:

St. Augustine, in works like On Free Choice of the Will, grappled with the question of how Evil could exist if God is perfectly Good. His answer placed the role squarely on human free will. Evil, for Augustine, is not a substance but a privation of Good, a turning away from God, made possible by the will's freedom to choose wrongly. This emphasizes the will's profound power, not just for Good, but also for the tragic possibility of Evil.

The consistent thread through these diverse perspectives is the recognition that human agency, our capacity to choose and intend, is fundamental to understanding morality, duty, and the eternal struggle between Good and Evil.

The Enduring Significance of Will in Moral Action

The will is far more than a simple desire; it is the engine of our moral lives. It is the faculty that allows us to understand our duties, to formulate maxims for our actions, and to strive towards what is truly Good, even when our inclinations pull us towards Evil. The philosophers of the "Great Books" have, in their varied ways, underscored this profound role.

In a world filled with complexities and moral ambiguities, the call to cultivate a Good will – one that consistently acts from duty and strives for universalizable principles – remains as relevant as ever. It is through the disciplined exercise of our will that we truly become moral agents, shaping not only our own character but also the moral fabric of society.

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Kant's Ethics: Categorical Imperative Explained" and "The Problem of Evil and Free Will - Augustine""