The Enduring Tapestry: Unraveling the Role of Labor in the Life of Man

The role of labor in the life of man is not merely an economic function; it is a profound philosophical inquiry, a cornerstone of our self-understanding, and a constant companion from birth to the very threshold of life and death. From the primal necessity of survival to the complex dynamics of self-realization and societal structure, labor shapes our existence, defines our values, and offers a lens through which we grapple with our place in the cosmos. This article delves into the rich philosophical history of labor, drawing from the Great Books of the Western World to explore its multifaceted significance and its indelible mark on the human condition.

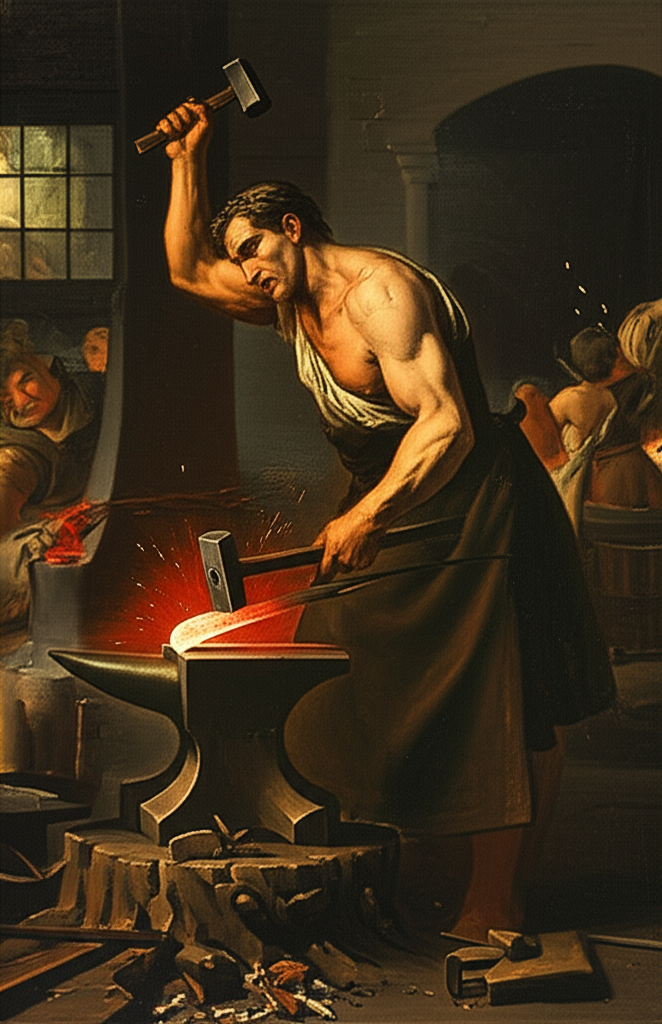

The Primal Urge: Labor as Survival and Transformation

At its most fundamental, labor is the human act of engaging with the world to sustain life. Before abstract thought or complex societies, early humans toiled to find food, build shelter, and protect themselves. This basic interaction with nature, transforming raw materials into necessities, is the origin of all later conceptions of work. Philosophers, even in antiquity, recognized this fundamental relationship. The very act of making or doing to survive is what differentiates man from mere existence, imbuing the world with human intention.

- Necessity: Labor as the means to fulfill basic physiological needs.

- Adaptation: The human capacity to modify the environment through work.

- Early Self-Definition: The first steps toward defining human identity through productive activity.

Labor and the Shaping of Self: From Alienation to Fulfillment

The relationship between labor and the individual's sense of self has been a central theme in philosophy. Is labor a burden, a curse, or a path to self-realization?

Ancient Perspectives: Dignity and Disdain

For many ancient Greek thinkers, particularly those in the Athenian polis, manual labor was often viewed with a degree of disdain, relegated to slaves or foreigners. Plato, in his Republic, outlines a society where different classes perform different functions, with artisans and farmers providing for the city, but the highest good was reserved for the philosophers and guardians, whose "work" was intellectual and political. Aristotle, in Politics, similarly distinguished between poiesis (making things) and praxis (action), valuing the latter, particularly political activity and contemplation, as the highest forms of human endeavor, requiring leisure away from the necessity of labor. For the free citizen, true life was found in leisure and civic engagement, not in the sweat of the brow.

However, even within these societies, the skilled artisan held a particular respect. The creation of beautiful and functional objects, while not the highest pursuit, demonstrated human ingenuity and craft.

The Modern Turn: Labor as Identity and Self-Formation

The Enlightenment and subsequent philosophical movements dramatically shifted the perception of labor. John Locke, in his Two Treatises of Government, famously argued that labor is the foundation of property. By mixing one's labor with natural resources, one imbues them with value and establishes ownership. This idea fundamentally linked individual effort to personal rights and the creation of wealth.

Later, G.W.F. Hegel, in his Phenomenology of Spirit, introduced the profound concept of labor as a means of self-consciousness and self-formation through the "master-slave dialectic." The slave, through his labor, transforms nature and, in doing so, transforms himself. He imposes his will on the material world, gaining a sense of his own agency and independence, eventually surpassing the master who merely consumes. This perspective elevates labor from a mere economic activity to a central pillar of human development and the realization of one's spirit.

Karl Marx, building on Hegel, critically examined the role of labor in industrial society. While acknowledging labor as humanity's "species-being" – the essential activity through which man realizes his potential and creates his world – he lamented its alienation under capitalism. For Marx, alienated labor separates the worker from:

- The product of his labor: He doesn't own what he makes.

- The act of labor itself: It's forced, not freely chosen.

- His species-being: He is reduced to an animal function, not a creative being.

- Other men: Competition replaces cooperation.

This alienation, Marx argued in his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, profoundly distorts the life of the worker, robbing him of meaning and contributing to a sense of existential emptiness.

The Social Fabric: Labor, Property, and Society

Labor is not an isolated act; it is deeply embedded in the social and economic structures of human societies. Philosophers have explored how labor organizes communities, creates wealth, and even generates conflict.

| Philosopher/Work | Key Concept | Impact on Society |

|---|---|---|

| Plato (Republic) | Division of Labor | Specialization leads to efficiency and social hierarchy; ideal state requires each to fulfill their role. |

| John Locke (Two Treatises of Government) | Labor Theory of Property | Justifies private ownership; provides basis for economic systems; links individual effort to rights. |

| Adam Smith (The Wealth of Nations) | Division of Labor, Invisible Hand | Increases productivity and wealth; self-interest in labor benefits society; foundations of modern capitalism. |

| Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Discourse on Inequality) | Labor and the Origin of Inequality | Private property, stemming from labor, leads to social stratification and the corruption of man. |

| Karl Marx (Das Kapital) | Alienated Labor, Exploitation | Labor under capitalism creates class struggle and injustice; calls for revolutionary change in economic systems. |

These diverse perspectives highlight that the role of labor extends far beyond individual effort, shaping the very fabric of our collective life.

Beyond Toil: Labor, Leisure, and the Good Life

If labor is essential, what is its ultimate purpose? Is it merely a means to an end, or does it hold intrinsic value? This question brings us to the concept of leisure and the pursuit of the "good life."

The Quest for Eudaimonia

Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, argued that the highest human good, eudaimonia (often translated as flourishing or true happiness), is achieved through virtuous activity, particularly contemplative life. For Aristotle, labor was necessary but not the end goal. Leisure, understood not as idleness but as purposeful activity (like philosophy, art, or politics), was crucial for the development of virtue and the pursuit of knowledge. The "free" man was one who had the leisure to pursue these higher ends. This perspective challenges us to consider what our labor ultimately serves: is it merely survival, or does it contribute to a richer, more meaningful existence?

Labor, Meaning, and Mortality: Facing Life and Death

Perhaps the most profound philosophical dimension of labor lies in its connection to life and death. In a world where our existence is finite, our labor becomes a way to leave a mark, to create something that outlives us, or to contribute to a legacy.

- Legacy: Through our work, we build, create, and innovate, leaving behind structures, ideas, and traditions that transcend our individual life spans.

- Meaning-Making: In a seemingly indifferent universe, labor can provide purpose and meaning. The craftsman finds meaning in the perfection of his art, the scientist in the pursuit of knowledge, the parent in raising a child. These acts of creation and care are fundamental to human significance.

- Confronting Finitude: The very act of working against the forces of decay and entropy – building, maintaining, repairing – is a testament to our will to live and thrive in the face of our own mortality. Our labor is a continuous affirmation of life in the shadow of death.

Conclusion: The Enduring Significance of Our Toil

From the ancient workshops of Athens to the sprawling factories of the industrial age, and now into the digital realms of the information economy, the role of labor has been a persistent thread in the tapestry of human existence. It is not a monolithic concept but a dynamic, evolving force that shapes our individual identities, structures our societies, and compels us to confront the deepest questions of life and death. Understanding labor, in all its philosophical complexity, is to understand a fundamental aspect of what it means to be man. As Chloe Fitzgerald, I believe that by reflecting on our toil, we can unearth profound truths about our purpose, our communities, and our enduring quest for meaning.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Great Books of the Western World on Labor and Property""

2. ## 📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Marx on Alienation and Human Nature Explained""