The Indispensable Role of Habit in Moral Education: Cultivating Virtue from Ancient Wisdom

In the grand tapestry of philosophical inquiry, few threads are as fundamental yet often overlooked as the profound influence of habit on our moral landscape. This pillar page argues that habit is not merely a collection of unconscious routines, but rather the very crucible in which moral character is forged. From the ancient Greek emphasis on character formation to Enlightenment treatises on self-governance, we will explore how philosophers across the Western tradition have illuminated the critical role of habit in moral education, shaping our capacity for virtue and guarding against vice, thereby influencing our understanding and execution of duty. This journey through the Great Books reveals that to live a good life, one must first learn to practice it.

The Foundation of Character: Why Habit Matters

At its core, moral education is the process by which individuals learn to distinguish right from wrong, and more importantly, develop the disposition to do what is right. It's not enough to simply know; one must also become. Here, habit transcends its superficial understanding as mere repetition and emerges as the bedrock of moral development.

Consider the simple act of practicing a musical instrument or a sport. Initially, every movement is conscious, awkward, and demanding. With persistent, deliberate practice – the formation of habits – these movements become fluid, intuitive, and eventually, a reflection of mastery. The same principle, philosophers contend, applies to our moral lives.

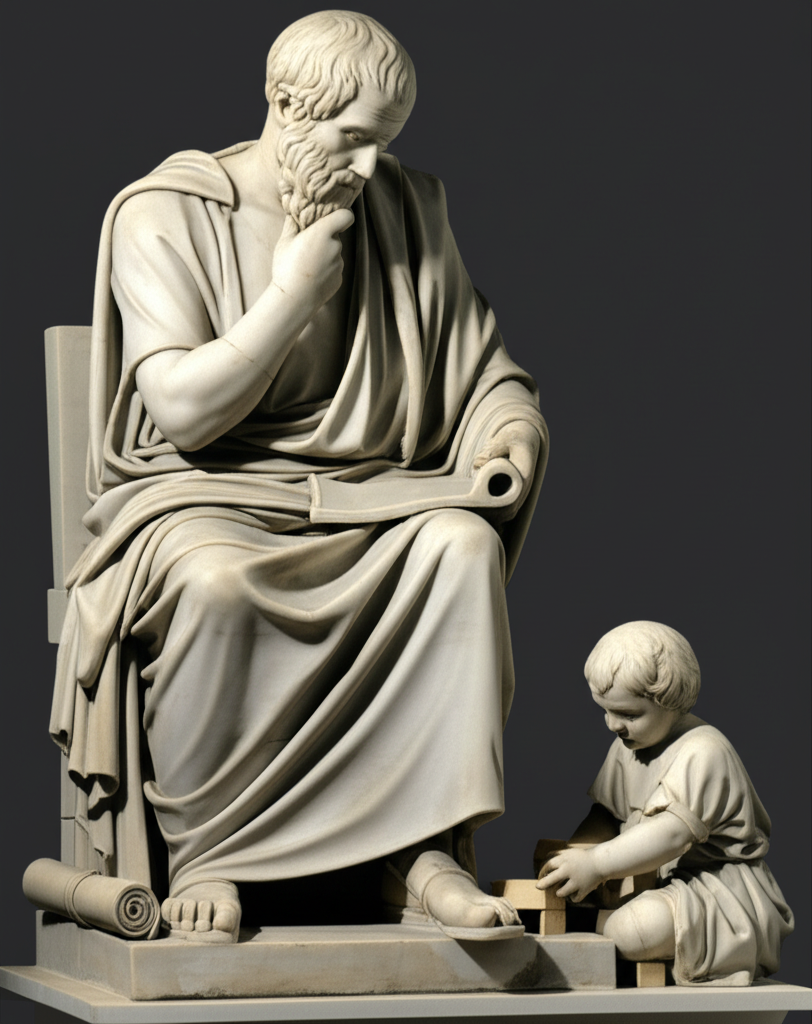

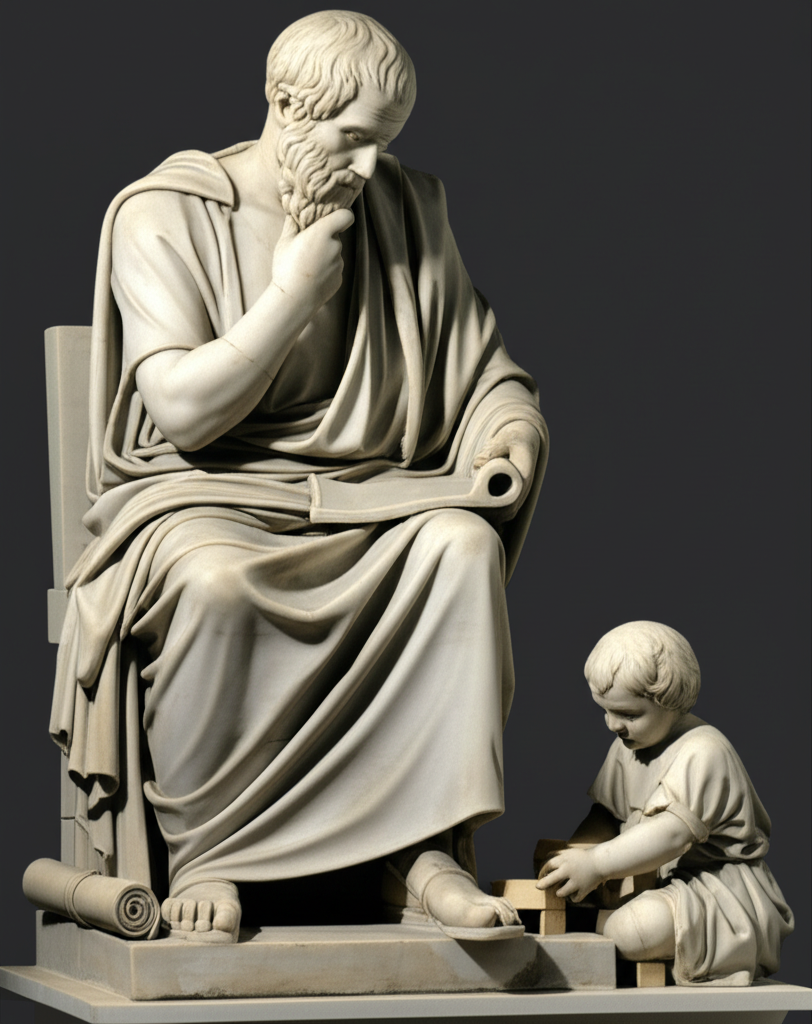

Aristotle and the Cultivation of Virtue

Perhaps no philosopher articulated the role of habit in moral formation more compellingly than Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics. For Aristotle, virtue (arête) is not an innate quality, nor is it purely intellectual knowledge. Instead, it is a hexis, a settled disposition or character trait, acquired through repeated action.

Key Aristotelian Insights on Habit:

- Virtue as a State of Character: "We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit." (Though often misattributed, this sentiment perfectly encapsulates Aristotle's view).

- Learning by Doing: Just as one becomes a builder by building, one becomes just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, and brave by doing brave acts. Moral learning is experiential and active.

- Early Education is Crucial: Aristotle stressed the immense importance of early education in instilling the right habits, as these form the foundational patterns of character. Children, by being habituated to noble actions, develop a taste and preference for them.

This isn't about rote memorization of rules, but about training our desires and shaping our emotional responses through consistent practice. The person who habitually acts courageously eventually becomes courageous, finding it easier and more natural to face fear appropriately.

From Practice to Virtue: The Aristotelian Model in Detail

Aristotle's ethical framework is deeply practical. He understood that human beings are not born virtuous, but possess the potential for virtue, which must be actualized through habituation.

The Golden Mean and Habitual Navigation

Aristotle famously posited that most virtues lie in a "golden mean" between two extremes, two vices: one of excess and one of deficiency. For instance, courage is the mean between rashness (excess) and cowardice (deficiency).

How do we find this mean? Not through abstract calculation in every instance, but through the development of a discerning character – a character shaped by habit. Through repeated virtuous actions, we cultivate practical wisdom (phronesis), which allows us to perceive the appropriate action in varying circumstances, almost instinctively.

| Virtue (Mean) | Vice of Deficiency | Vice of Excess | Habitual Practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Courage | Cowardice | Rashness | Facing fears appropriately, standing up for what's right. |

| Temperance | Insensibility | Self-indulgence | Moderating desires, disciplined consumption. |

| Generosity | Stinginess | Prodigality | Giving appropriately, sharing resources wisely. |

| Honesty | Deceptiveness | Blatantness | Speaking truth with tact, avoiding falsehoods. |

Duty as an Outgrowth of Habitual Virtue

While later philosophers like Kant would emphasize duty as an obligation derived from rational principle, for Aristotle, duty emerges more organically. When virtuous habits are deeply ingrained, acting virtuously becomes a natural inclination, a part of one's identity. The duty to act justly, for example, is not merely an external command but an internal imperative stemming from a well-formed character. The virtuous person wants to do what is right, and does so consistently, often without laborious deliberation.

The Stoic Discipline: Habit and the Will

Moving forward, the Stoics offered another powerful perspective on habit's role in moral life, particularly concerning the discipline of the mind and the will. Thinkers like Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius (Meditations) emphasized the constant training required to live in accordance with reason and nature.

For the Stoics, habit was crucial for:

- Controlling Impressions: Training oneself to distinguish between what is within one's control (thoughts, judgments, desires) and what is not (external events, other people's actions). This requires consistent, habitual mental discipline.

- Cultivating Apathy (Apatheia): Not indifference, but freedom from irrational passions. This is achieved through habitual practice of examining one's reactions and aligning them with reason.

- Living in Accordance with Nature: The Stoic ideal of virtue involved living rationally. This duty was fulfilled through daily, conscious effort to align one's actions, thoughts, and emotions with a reasoned understanding of the cosmos. It's a continuous process of self-correction and habitual philosophical practice.

The Enlightenment and the Formation of Moral Sensibility

The Enlightenment era continued to explore the mechanisms of moral formation, often with a focus on reason and individual development, but still acknowledging the power of habit.

- John Locke's Some Thoughts Concerning Education: Locke, a foundational empiricist, stressed the paramount importance of early education in forming good habits. He believed that children's minds are like "white paper" and that parents and tutors have a tremendous duty to instill self-control, reason, and virtue through consistent training and example. The habit of deferring gratification, for instance, was seen as crucial for developing a rational and morally upright individual.

- Adam Smith's The Theory of Moral Sentiments: Smith, beyond his economic theories, delved into the psychological basis of morality. He argued that our moral judgments are shaped by our capacity for sympathy and our habitual imagining of an "impartial spectator." Through repeated social interactions and reflections, we develop a sense of what is praiseworthy or blameworthy, thereby cultivating our moral sentiments and sense of duty.

The Double-Edged Sword: Habit, Vice, and Moral Decay

While habit is a powerful tool for cultivating virtue, it is equally potent in the service of vice. Bad habits, once ingrained, can lead to moral decay and make the path to virtue exceedingly difficult.

Saint Augustine, in his Confessions, offers a poignant account of the struggle against ingrained vice. His narrative vividly illustrates how sinful habits can bind the will, making it incredibly challenging to choose the good, even when one knows it. He describes habit as a "chain" or a "sweet bondage" that, once formed, requires immense effort and divine grace to break.

The danger of vice is precisely its self-perpetuating nature: each indulgence strengthens the habit, making the next transgression easier and the resistance weaker. Moral education, therefore, is not just about building good habits but also about consciously dismantling bad ones.

Modern Relevance: Cultivating Moral Habits in Contemporary Education

The insights from these philosophical giants remain profoundly relevant today. In an age of instant gratification and moral relativism, the deliberate cultivation of moral habit in education is more critical than ever.

Practical Applications for Moral Education:

- Intentional Practice: Just as we teach academic subjects, we must intentionally teach and model virtuous behaviors. This means creating opportunities for students to practice honesty, empathy, perseverance, and responsibility.

- Role Modeling: Educators, parents, and community leaders have a duty to embody the virtues they wish to instill. Children learn as much, if not more, from observing the habits of those around them.

- Environment Design: Creating environments that are conducive to virtuous choices and make vicious ones more difficult. This could involve curriculum design, classroom management, or community initiatives.

- Reflection and Self-Correction: Encouraging students to reflect on their actions, identify areas for improvement, and develop strategies for cultivating better habits. This fosters self-awareness and moral autonomy.

Ultimately, the philosophical tradition teaches us that moral education is an ongoing, active process of self-sculpting. It is through the consistent, deliberate practice of good habits that we move beyond mere knowledge of right and wrong, transforming ourselves into individuals who instinctively choose the good, fulfill our duty, and live lives of genuine virtue.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

- Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics Virtue Ethics Explained

- Stoicism Habits and Discipline Marcus Aurelius

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Role of Habit in Moral Education philosophy"