The Enduring Architecture of Character: Habit's Pivotal Role in Moral Education

Moral character, often perceived as an innate quality or a sudden revelation, is in truth a carefully constructed edifice, built brick by brick through the persistent, often unseen, work of habit. Far from being a mere intellectual exercise, moral education is fundamentally a process of habituation, where repeated actions, guided by intention and insight, shape our deepest dispositions. It is through this diligent cultivation that we foster virtues, mitigate vices, and ultimately align our lives with a sense of duty and ethical fulfillment. This pillar page delves into the profound philosophical underpinnings of habit in moral formation, drawing wisdom from the "Great Books of the Western World" to illuminate how our daily practices become the very architects of who we are.

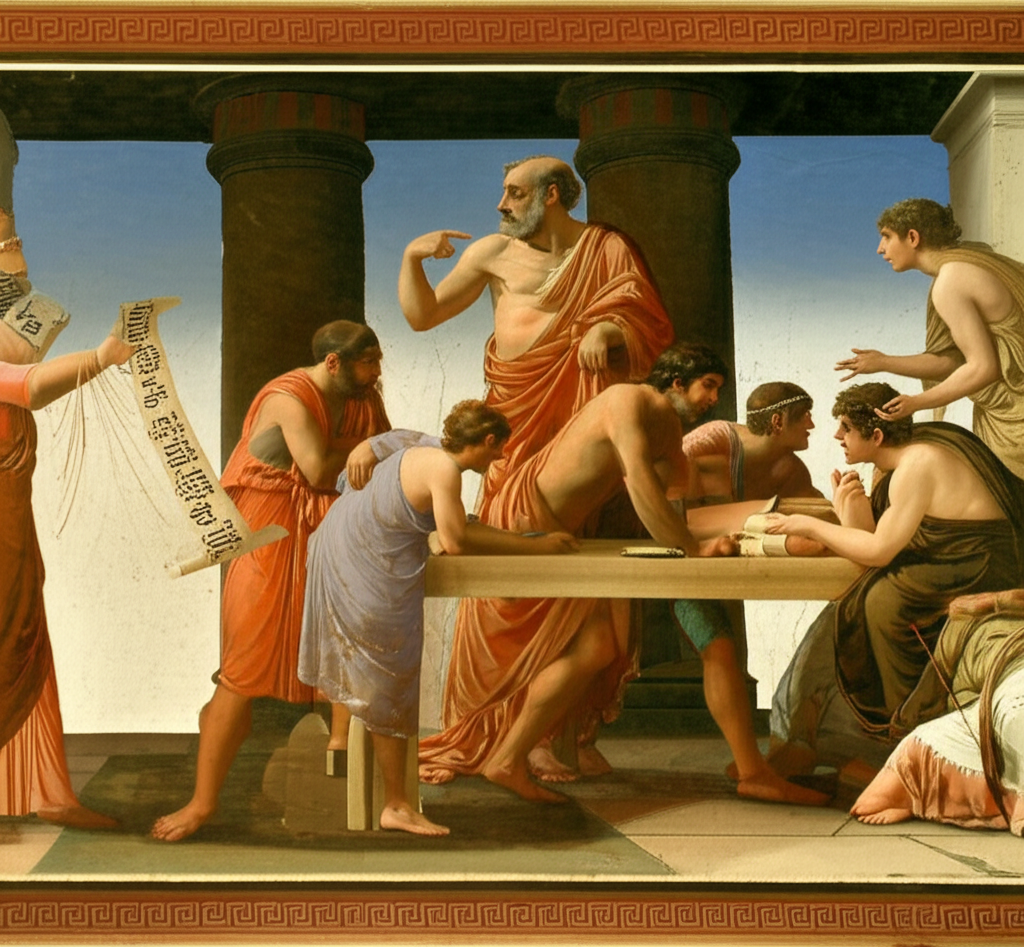

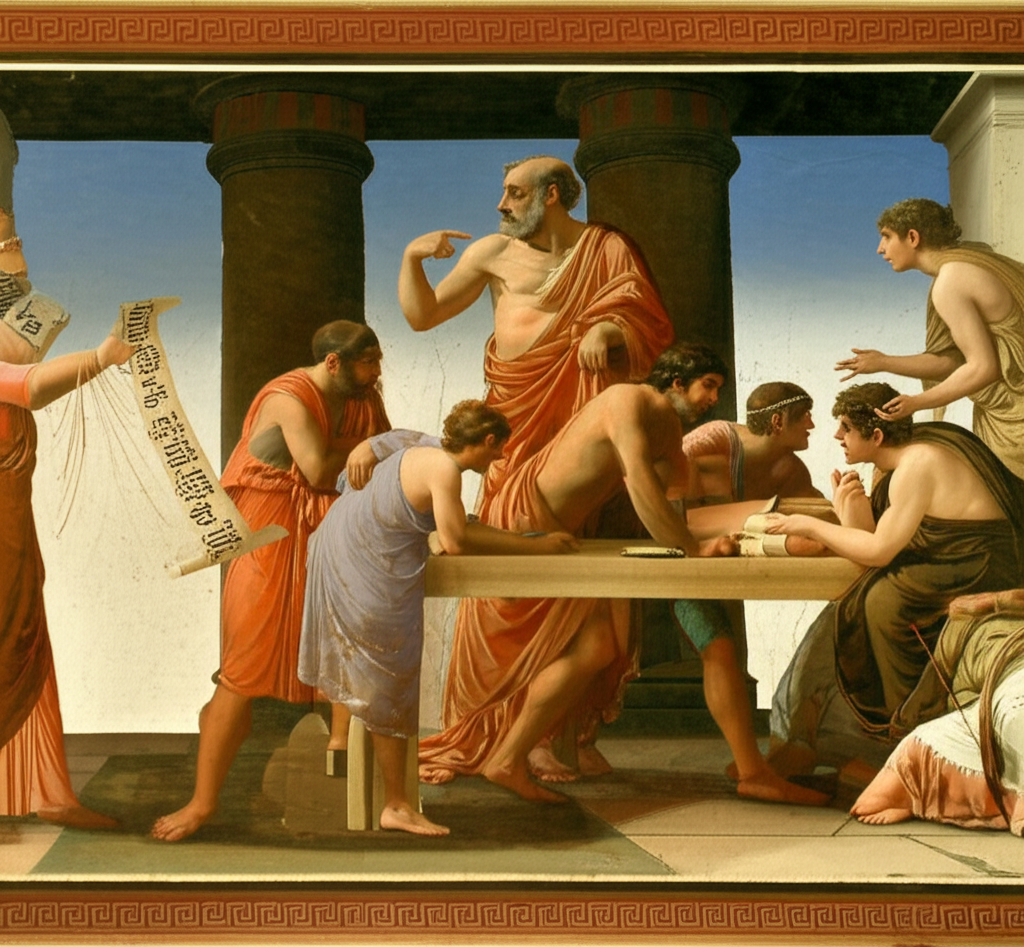

The Ancient Roots of Habit: Aristotle's "Second Nature"

The idea that habit forms character is not a modern innovation but a cornerstone of ancient Greek philosophy. Perhaps no thinker articulated this more clearly than Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics. For Aristotle, virtue (aretê) is not something we are born with, nor is it merely intellectual knowledge. Instead, it is a hexis, a settled disposition or character trait, acquired through practice.

- Virtue as a Skill: Just as one becomes a skilled musician by playing music, or a builder by building, one becomes just by performing just acts, and courageous by performing courageous acts. Moral virtues, therefore, are habits of choice.

- The Golden Mean: Aristotle taught that virtue lies in a mean between two extremes of vice – one of excess and one of deficiency. For example, courage is the mean between recklessness (excess) and cowardice (deficiency). Developing the habit of choosing this mean requires practical wisdom (phronesis) and consistent practice.

Table 1: Aristotelian Virtues and Their Corresponding Vices

| Virtue (Mean) | Vice of Deficiency | Vice of Excess |

|---|---|---|

| Courage | Cowardice | Rashness |

| Temperance | Insensibility | Self-indulgence |

| Liberality | Illiberality | Prodigality |

| Magnificence | Pettiness | Vulgarity |

| Gentleness | Irascibility | Spiritlessness |

This emphasis on doing – on the active, repeated engagement with ethical choices – underscores that moral education is not just about learning what is right, but practicing what is right until it becomes a part of one's very being.

Habit as the Architect of Virtue and Vice

Our character, the sum total of our moral inclinations, is less a blueprint drawn at birth and more a sculpture continually refined by our actions. Every choice, every response, every repeated behavior carves away at the marble of our potential, revealing either the noble form of virtue or the distorted shape of vice.

- The Power of Repetition: It is through consistent repetition that actions become ingrained. A single act of honesty is commendable, but a life lived honestly is a testament to the habit of truthfulness. Conversely, small compromises, when repeated, can solidify into habits of deceit or negligence.

- Moral Muscle Memory: Think of habit as moral muscle memory. When faced with an ethical dilemma, a person habituated to honesty will find it easier, almost natural, to speak the truth, even under pressure. For someone habituated to deceit, the path of falsehood might feel more familiar. This isn't to say we lose free will, but that our choices become easier or harder depending on the grooves our habits have worn.

- Early Education's Crucial Role: Plato, in his Republic, stresses the profound importance of early education in shaping character. He argues that children must be exposed to beautiful and good things from an early age, as these early impressions and habits formed in youth become deeply ingrained and difficult to alter later in life. The stories we tell, the games we play, the discipline we instill – all contribute to the moral habits that will define future citizens.

Duty, Reason, and the Discipline of Habit

While the Aristotelian view emphasizes habit as the direct path to virtue, other philosophical traditions offer a different lens, particularly concerning the concept of duty. Immanuel Kant, a towering figure in the "Great Books," places reason and duty at the core of morality. For Kant, an action is truly moral only if it is performed out of respect for the moral law, not out of inclination or habit.

However, even within a Kantian framework, habit plays a crucial, albeit distinct, role:

- Enabling Duty: While Kant might argue that acting from habit doesn't confer moral worth, acting in accordance with duty, consistently and reliably, often requires the discipline that habit provides. To reliably perform one's duties – whether to oneself or to others – requires a certain strength of character and consistency of action that is fostered through repeated, intentional choices.

- Overcoming Inclination: Habits of self-control, diligence, and truthfulness, though not the source of moral worth in Kant's view, are instrumental in helping individuals overcome inclinations that might lead them astray from their duty.

- The Practice of Moral Strength: The sustained effort to act according to moral principles, even when it's difficult, builds a kind of moral resilience. This resilience, a form of inner strength, is developed through the regular exercise of the will, which is, in essence, the formation of habits of moral action.

Therefore, whether one sees habit as directly constituting virtue (Aristotle) or as providing the necessary discipline to fulfill duty (Kant), its significance in moral education remains undeniable.

Moral Education in Practice: Cultivating Ethical Dispositions

Understanding the philosophy of habit is one thing; applying it in the real world of moral education is another. How do we, as individuals and as a society, cultivate those habits that lead to virtue and ethical living?

- Conscious Awareness: The first step is to become aware of our existing habits, both good and bad. This requires introspection and honest self-assessment. What actions do we repeat without thinking? How do these align with our stated values?

- Intentional Practice: Virtue is not accidental. It requires deliberate practice. Identify a specific virtue (e.g., patience, honesty, generosity) and consciously seek opportunities to act in accordance with it. Start small, celebrate progress, and persist through setbacks.

- Role Models and Mentorship: Learning from those who embody the virtues we aspire to is invaluable. Observing their actions, understanding their decision-making processes, and seeking their guidance can provide a powerful impetus for habit formation.

- Creating Supportive Environments: Our environment profoundly influences our habits. Surrounding ourselves with people, ideas, and structures that encourage ethical behavior makes it easier to cultivate good habits and harder to fall into vice. This is where the broader societal role of education comes into play – creating institutions and cultural norms that support moral development.

- Reflective Practice: Regularly reflect on your actions and their consequences. Did a particular habit serve you well? Did it lead to a virtuous outcome? This continuous feedback loop helps refine and strengthen positive habits.

YouTube: Search for "Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics Habit Virtue" for an accessible overview of Aristotle's thought on character development.

YouTube: Search for "Kant Duty Ethics Explained" to understand the role of duty and reason in moral philosophy.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Journey of Self-Sculpture

The role of habit in moral education is not merely academic; it is profoundly practical and deeply personal. From the ancient Greeks who saw virtue as a practiced disposition, to later thinkers who emphasized the discipline required for duty, the consistent thread is that character is not given, but forged. Every choice we make, every action we undertake, contributes to the intricate tapestry of who we are becoming. By consciously engaging with the power of habit, we become active participants in our own moral formation, cultivating the virtues that uplift us, mitigating the vices that diminish us, and fulfilling our deepest sense of duty to ourselves and to the world. It is an ongoing journey of self-sculpture, where the daily practice of goodness ultimately shapes the very architecture of our souls.

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Role of Habit in Moral Education philosophy"