The Indispensable Role of Desire in Shaping Virtue and Vice

Desire, often misconstrued as a mere impulse to be suppressed or indulged, plays a foundational and profoundly complex role in the development of both virtue and vice. Far from being inherently good or evil, desire acts as a potent, morally neutral force that, when properly understood, guided by reason, and directed by a well-formed will, can propel us towards excellence. Conversely, when unchecked, misdirected, or left to its own devices, desire can lead directly to moral failing and the embrace of vice. This exploration, deeply rooted in the Western philosophical tradition, reveals desire not as a simple urge, but as a critical component in the architecture of the human moral life.

The Dual Nature of Desire: A Philosophical Inquiry

From the earliest inquiries into human nature, philosophers have grappled with the pervasive presence of desire. It is the engine of action, the spark of ambition, and the source of many of our joys and sorrows. Yet, its inherent power makes it a double-edged sword. Is desire merely a base appetite, a pull towards immediate gratification, or does it encompass loftier aspirations like the desire for truth, beauty, or justice? The answer, as the great thinkers suggest, is both. The moral quality of desire is not intrinsic to its existence but is conferred by its object and, crucially, by the will that governs its pursuit.

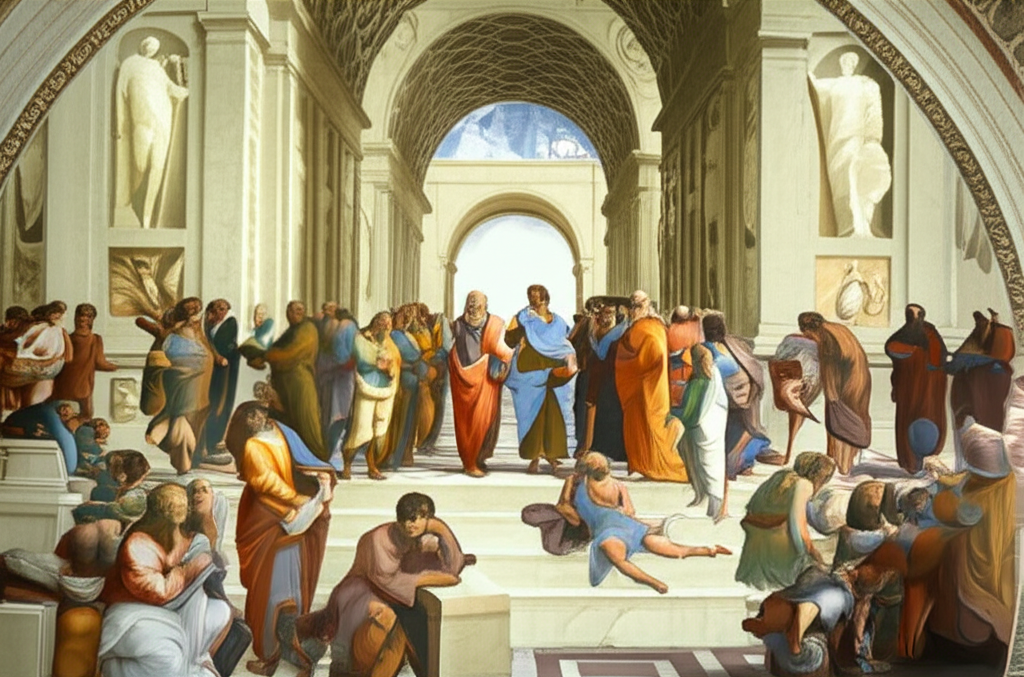

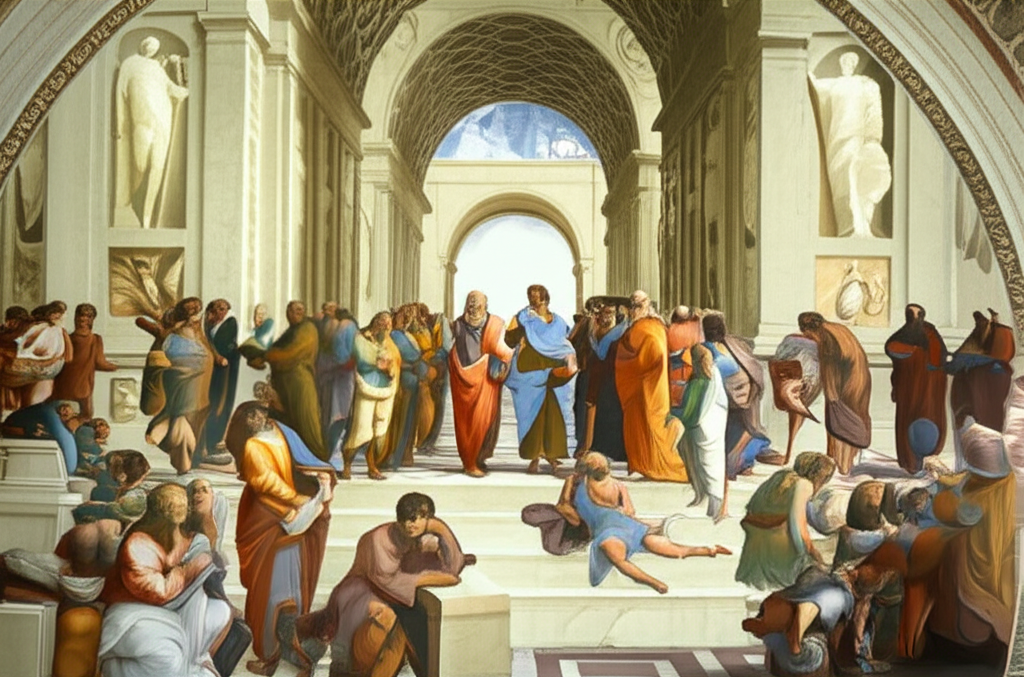

Ancient Perspectives: Guiding the Appetites

The classical Greek philosophers were keenly aware of the role of desire.

- Plato's Tripartite Soul: In Plato's Republic, he famously describes the soul as having three parts: the rational, the spirited, and the appetitive. The appetitive part, responsible for basic desires like hunger, thirst, and sexual urges, is powerful and often unruly. For virtue to flourish, the rational part of the soul, akin to a charioteer, must guide and control the spirited and appetitive horses. When desire is allowed to dominate, it leads to intemperance and injustice, illustrating its profound role in vice.

- Aristotle's Ethics of Character: Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, offers a more nuanced view. He acknowledges desire as a fundamental motivator, but emphasizes that virtue is not merely the absence of desire, but the proper direction and moderation of it. For Aristotle, virtue is a mean between extremes, achieved through habituation and practical wisdom (phronesis). A truly virtuous person doesn't suppress all desires, but rather desires the right things, at the right time, in the right way, and for the right reasons. The will to consistently choose these virtuous actions, thereby shaping one's character and desires, is paramount.

Medieval Synthesis: The Will's Dominion over Passion

The Christian philosophical tradition, drawing heavily from the Greeks, further elaborated on the role of desire, particularly in relation to sin and salvation.

- Augustine on Disordered Love: St. Augustine of Hippo viewed sin as a form of "disordered love" or desire. While desire for God is inherently good, concupiscence—the inclination towards earthly pleasures and goods above spiritual ones—is a profound manifestation of fallen human nature. Here, the will plays a central role: it is through the will's turning away from God and towards lesser desires that vice takes root.

- Aquinas and the Rational Appetite: St. Thomas Aquinas, synthesizing Aristotle with Christian theology, understood passions (which include desires) as morally neutral until they are acted upon by the will, guided by reason. For Aquinas, the will itself is a "rational appetite"—it desires the good as apprehended by reason. Thus, virtuous actions stem from a will that desires the true good, while vicious actions arise from a will that assents to desires for apparent or lesser goods, contrary to reason.

The Modern Lens: Duty Versus Inclination

Immanuel Kant, a pivotal figure in modern philosophy, presented a stark contrast between desire (inclination) and moral duty.

- Kant's Good Will: For Kant, an action is truly moral only if it is performed from duty, not from mere desire or inclination. While acting from desire might incidentally align with what is good, it lacks true moral worth because it is contingent and unreliable. The will, acting in accordance with universal moral law (the Categorical Imperative), is the sole source of moral virtue. Here, desire is often seen as a potential impediment to moral action, requiring the will to overcome its pull.

The Indispensable Role of the Will

Across these diverse philosophical landscapes, a common thread emerges: the will serves as the critical mediator between raw desire and the cultivation of virtue or vice. The will is the faculty of choice, the power to assent to or resist our desires. It is through the will that we:

- Direct Desire: The will can guide desire towards noble ends or allow it to stray towards destructive ones.

- Moderate Desire: It enables us to find the appropriate measure, preventing both excess and deficiency.

- Educate Desire: Through repeated choices, the will can habituate our desires, shaping them over time to align with reason and the good.

Without a well-formed and rightly directed will, desire remains a wild, unpredictable force, prone to leading us astray into various forms of vice. With a strong will, however, desire transforms into a powerful ally in the pursuit of virtue.

Cultivating Virtuous Desires: A Practical Philosophy

Given the profound role of desire, the cultivation of virtue necessarily involves the education and refinement of our appetites. This is not about eradication, but about orientation.

Consider the following contrasts:

- Virtuous Desires (Directed by Reason & Will):

- The desire for knowledge, leading to wisdom and intellectual growth.

- The desire for justice, inspiring actions of fairness and equity.

- The desire for temperance, moderating appetites for pleasure and comfort.

- The desire for courage, enabling one to face fear for a noble cause.

- Vicious Desires (Unchecked or Misdirected):

- The desire for excessive pleasure, leading to gluttony, debauchery, or hedonism.

- The desire for unbridled power, culminating in tyranny and oppression.

- The desire for wealth for its own sake, fostering greed and avarice.

- The desire for revenge, perpetuating hatred and injustice.

The path to virtue is therefore a continuous process of self-reflection, rational deliberation, and the consistent exercise of the will to shape our desires in accordance with the good.

Conclusion

The role of desire in the interplay of virtue and vice is undeniably central to the human condition. From the ancient Greeks to the modern era, philosophers have consistently recognized desire as a fundamental, potent force within us. It is neither inherently good nor evil, but its moral valence is determined by its object and, most critically, by the guiding hand of the will. A life of virtue is not one devoid of desire, but rather one in which desires are harmonized with reason and directed towards genuine human flourishing by a strong and well-trained will. To understand ourselves, we must understand our desires, for in their intricate dance with the will, the very fabric of our moral character is woven.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Chariot Allegory Explained""

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics Desire Virtue Willpower""