The Enduring Question: Labor, Freedom, and Chains

The relation between labor and slavery is one of the most profound and unsettling inquiries into the nature of Man's existence, freedom, and dignity. While fundamentally distinct – one implying free will and self-ownership, the other forced servitude – philosophical traditions, particularly those explored in the Great Books of the Western World, reveal a complex continuum where the lines often blur, challenging our understanding of what it means to work and to be truly free. This article delves into the historical and philosophical distinctions, examining how various thinkers have grappled with the profound implications of how Man engages with his world through work.

Ancient Roots: Aristotle and the "Natural Slave"

To understand the relation between labor and slavery, we must first journey back to antiquity, where the concept of slavery was not only widespread but philosophically justified. In his Politics, Aristotle presents a controversial yet foundational argument for what he termed the "natural slave." For Aristotle, some men are by nature fitted to be slaves, possessing sufficient reason to understand commands but lacking the deliberative faculty necessary for self-governance.

- Instrumental View: The slave is seen as a "living tool," an instrument of action for the master, much like an ox or a plow. Their labor serves the master's household, freeing the citizen for political life and philosophical contemplation.

- Capacity for Reason: The distinction is crucial: it's not about the capacity for physical labor, but the capacity for rational self-direction. Those naturally lacking this higher reason, Aristotle argued, benefit from the guidance of a master.

While abhorrent to modern sensibilities, Aristotle's framework provided a powerful, albeit flawed, philosophical underpinning for slavery, casting it as a natural state for some men and a necessary condition for the flourishing of the polis. It directly tied the man's inherent nature to his social and economic role, blurring the lines between identity and servitude.

The Dawn of Liberty: Locke on Labor and Property

Centuries later, the Enlightenment brought a radical re-evaluation of Man's natural rights and the concept of labor. John Locke, in his Two Treatises of Government, laid the groundwork for modern liberal thought by asserting that every man has a property in his own person. This fundamental premise had profound implications for the relation between labor and freedom:

- Self-Ownership: A man's own person and the labor of his body are his own. This self-ownership is inalienable.

- Source of Property: When a man mixes his labor with something from the common stock of nature, he makes it his property. The act of labor itself is the origin of property rights.

Locke's philosophy established labor as an act of freedom and self-expression, a direct antithesis to slavery. To enslave a man was to deny him ownership of his person and his labor, stripping him of his most fundamental right. This intellectual shift was instrumental in challenging the legitimacy of chattel slavery and defining free labor as a cornerstone of human dignity and liberty.

Modern Critiques: Marx, Alienation, and Wage Slavery

With the advent of industrial capitalism, the philosophical lens on labor shifted once more. While chattel slavery was being abolished across the Western world, Karl Marx, drawing heavily from the Hegelian tradition, argued in works like Das Kapital and his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 that a new form of servitude had emerged: "wage slavery."

Marx contended that under capitalism, the relation of the worker to his labor becomes deeply problematic:

- Alienated Labor: The man is alienated from the product of his labor (which belongs to the capitalist), the process of labor itself (which is externally imposed), his species-being (his creative essence), and from other men.

- Commodification of Labor: Labor power becomes a commodity, bought and sold in the market. The worker sells his capacity to labor for a wage, not because he freely chooses to express himself, but out of economic necessity.

- Exploitation: The value created by the worker's labor exceeds the wage he receives, with the surplus value going to the capitalist. This exploitation, for Marx, is the essence of capitalist production.

For Marx, while legally free, the wage worker is still bound by economic chains, forced to labor for another's profit, much like a slave, albeit with a different mechanism of coercion. The man remains unfree, his labor serving not his own self-realization but the accumulation of capital.

Distinctions and Overlaps: A Philosophical Synthesis

The journey through these philosophical perspectives reveals that while classical slavery and free labor stand as polar opposites, the nuances of economic and social structures can create conditions that blur the relation.

| Feature | Classical Slavery | Free Labor | Marxist "Wage Slavery" |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership | Man as property; owner controls person & labor | Self-ownership of person and labor | Legal self-ownership, but economic dependency |

| Volition | Forced, coerced, no choice; utter lack of freedom | Voluntary choice to work, contract based on consent | Voluntary contract, often under economic duress |

| Purpose of Labor | For the benefit and profit of the owner | For self-realization, sustenance, creating property | For employer's profit, subsistence for the worker |

| Dignity of Man | Denied; treated as an instrument, not a person | Affirmed; source of identity, rights, and autonomy | Compromised by alienation, commodification, and exploitation |

| Freedom | Utter absence of freedom | Essential component; ability to dispose of one's labor | Limited or illusory; constrained by economic necessity |

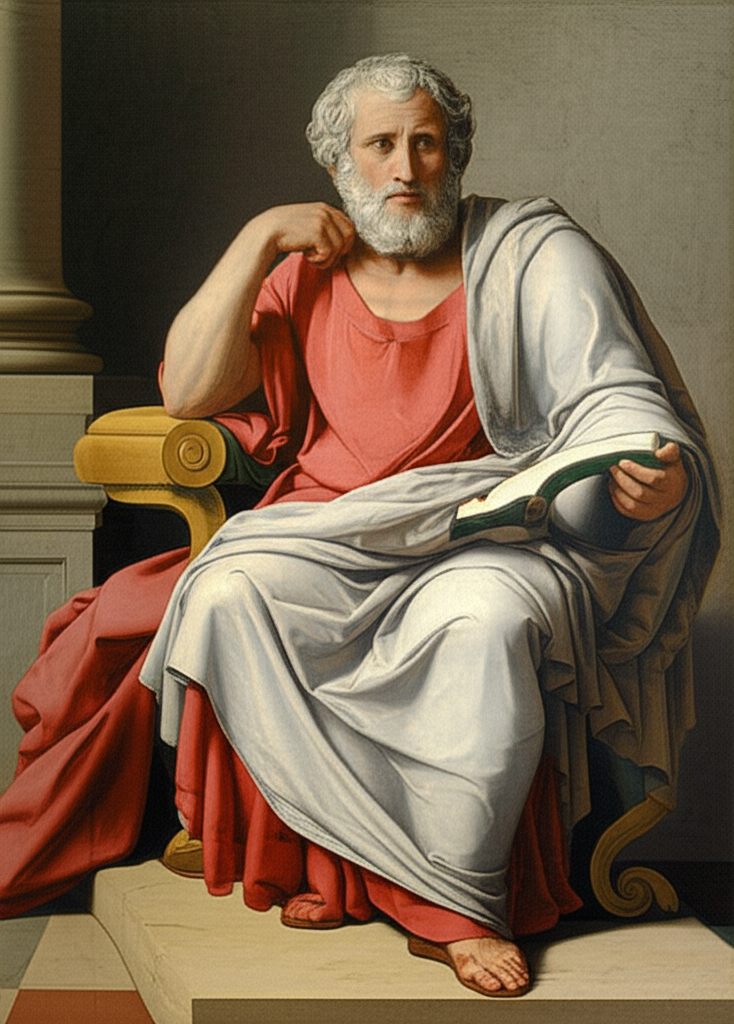

holding a scroll, observing two figures: one, a robust artisan freely crafting a vase with tools laid out before him, representing dignified labor; the other, a shadowed figure in chains, toiling under the gaze of an overseer, symbolizing forced slavery. The background subtly transitions from a sunlit, bustling marketplace to a darker, more oppressive landscape, illustrating the stark contrast and the complex philosophical relation between the two states of man.)

holding a scroll, observing two figures: one, a robust artisan freely crafting a vase with tools laid out before him, representing dignified labor; the other, a shadowed figure in chains, toiling under the gaze of an overseer, symbolizing forced slavery. The background subtly transitions from a sunlit, bustling marketplace to a darker, more oppressive landscape, illustrating the stark contrast and the complex philosophical relation between the two states of man.)

Conclusion: The Unfinished Work of Freedom

The relation between labor and slavery is not merely a historical curiosity but a living philosophical challenge. From Aristotle's attempts to categorize Man into natural masters and slaves, to Locke's revolutionary assertion of self-ownership through labor, to Marx's critique of alienated work under capitalism, the Great Books of the Western World continually force us to examine the conditions under which Man lives and works.

The abolition of chattel slavery was a monumental step towards recognizing the inherent dignity of every man. However, the persistent philosophical questions surrounding exploitation, alienation, and economic coercion remind us that the work of ensuring true freedom in labor is an ongoing endeavor. It demands continuous vigilance, critical inquiry, and a commitment to creating societies where every man's labor is an expression of his autonomy and a path to flourishing, rather than a chain that binds him.

Further Philosophical Exploration:

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle on Natural Slavery Explained""

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Karl Marx Alienated Labor Summary""