The Pursuit of Pleasure and the Good Life: A Philosophical Journey Through Desire and Happiness

The Age-Old Quest: Is Pleasure the Path to a Flourishing Existence?

From the dawn of philosophy, humanity has grappled with a fundamental question: What constitutes the good life? Is it a life brimming with pleasure, a relentless pursuit of gratification and contentment? Or is there a deeper, more profound meaning to happiness that transcends mere sensation? This pillar page delves into the rich tapestry of philosophical thought surrounding these questions, exploring how thinkers from ancient Greece to the modern era have understood the intricate relationship between pleasure and pain, the relentless pull of desire, and the ultimate meaning of life and death in our quest for flourishing. We will journey through hedonistic ideals, eudaimonic virtues, and the complex psychological landscapes painted by some of history's greatest minds, uncovering diverse perspectives that continue to shape our understanding of what it truly means to live well.

Defining the Elusive: What Are Pleasure and the Good Life?

Before we embark on our philosophical expedition, it's crucial to establish a working understanding of our core concepts. What exactly do we mean by "pleasure," and how does it relate to the broader, often more ambiguous notion of "the good life"?

Pleasure: Sensation, Satisfaction, and Tranquility

Pleasure can manifest in myriad forms. It can be the immediate, visceral sensation of a delicious meal or a warm embrace. It can be the intellectual satisfaction derived from solving a complex problem or understanding a profound idea. For some, pleasure is the absence of pain and disturbance, a state of serene tranquility. Philosophers have long debated whether all pleasures are equal, or if there are "higher" and "lower" forms.

The Good Life: More Than Just Feeling Good

While pleasure is often a component, the good life is generally understood as something more comprehensive. It speaks to a life of fulfillment, purpose, and flourishing. This concept, often termed eudaimonia in ancient Greek philosophy, implies a state of living well and doing well, often achieved through virtuous activity and the realization of one's potential. It's a life worth living, irrespective of transient moments of joy or sorrow.

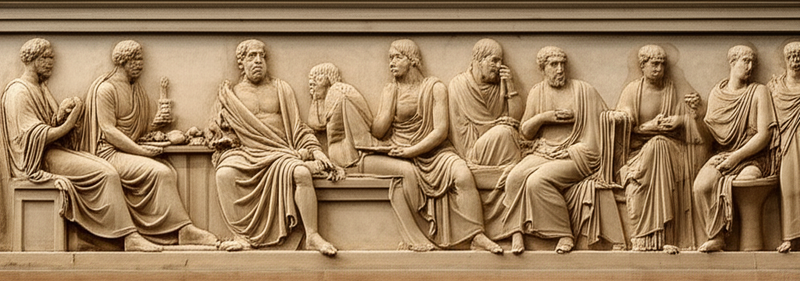

Ancient Voices: Hedonism, Eudaimonia, and the Mastery of Desire

The quest for the good life finds some of its earliest and most profound articulations in ancient Greece. Here, two distinct paths emerged: the direct pursuit of pleasure (hedonism) and the cultivation of virtue for flourishing (eudaimonia).

Early Hedonism: The Immediate Embrace of Sensation

The Cyrenaics, followers of Aristippus, championed a radical form of hedonism. They believed that immediate, intense bodily pleasure was the sole good, and pain the sole evil. For them, the present moment was paramount, and the wise person seized every opportunity for gratification, dismissing future consequences or past regrets. This philosophy, while seemingly straightforward, often led to a life driven by insatiable desire.

Epicureanism: Pleasure as Tranquility and Absence of Pain

A more nuanced form of hedonism emerged with Epicurus. Unlike the Cyrenaics, Epicurus did not advocate for a life of boundless indulgence. Instead, he defined pleasure primarily as the absence of pain in the body (aponia) and disturbance in the soul (ataraxia). For Epicurus, the greatest pleasures were found in simple living, friendship, philosophical contemplation, and the elimination of fear, particularly the fear of the gods and the fear of death. He famously argued that "death is nothing to us; for that which is dissolved is without sensation, and that which lacks sensation is nothing to us." This perspective offered a profound way to manage desire by distinguishing between natural and necessary desires (easily satisfied), natural but unnecessary desires (for luxury, to be approached with caution), and vain desires (unlimited and to be avoided).

Aristotle and Eudaimonia: Happiness Through Virtuous Activity

Perhaps the most enduring ancient perspective on the good life comes from Aristotle, particularly in his Nicomachean Ethics. For Aristotle, happiness (eudaimonia) is not merely a feeling or a state of pleasure, but an activity, a flourishing achieved through living in accordance with virtue. He argued that humans, by nature, are rational beings, and our highest good lies in exercising our unique rational capacities excellently. This involves cultivating virtues like courage, temperance, justice, and wisdom. Pleasure, for Aristotle, is a natural accompaniment to virtuous activity, a sign that one is engaging in an activity that fulfills one's nature, but it is not the goal itself. The good life, therefore, is a life of active engagement, moral excellence, and intellectual contemplation.

The Stoics: Mastering Desire and Accepting Fate

While not directly focused on pleasure, the Stoics (Epictetus, Seneca, Marcus Aurelius) offered a powerful framework for achieving inner peace and a good life by mastering desire and accepting what is beyond one's control. They taught that true happiness comes from living in accordance with reason and virtue, cultivating indifference to external events (like pleasure and pain, wealth, or reputation), and focusing solely on what is within one's power: one's judgments, actions, and attitudes. The fear of death, like all other fears, was to be faced with equanimity, recognizing it as a natural part of life and death.

The Intricate Dance of Pleasure, Pain, and Desire

The relationship between pleasure and pain is often more complex than a simple dichotomy. Many philosophers have observed their cyclical nature, their interdependence, and their profound impact on human desire.

Schopenhauer: The Will and the Pendulum of Suffering

Arthur Schopenhauer presented a stark view of human existence, arguing that life is driven by a blind, insatiable "Will" — a relentless, unconscious desire for existence and gratification. For Schopenhauer, pleasure is merely the temporary cessation of pain caused by unfulfilled desire. Once a desire is satisfied, boredom quickly sets in, leading to new desires and thus new pain. Life, he famously depicted, is a pendulum swinging between pain and boredom. True peace, for Schopenhauer, lay in transcending the Will through aesthetic contemplation or asceticism, moving beyond the endless cycle of desire and suffering that characterizes life and death.

Nietzsche: Affirmation, Suffering, and the Will to Power

Friedrich Nietzsche, while acknowledging suffering, offered a radically different perspective. He criticized philosophical systems that sought to escape pain or deny desire, viewing them as life-denying. For Nietzsche, suffering is not merely something to be avoided, but a necessary component of growth, self-overcoming, and the affirmation of life. The "Will to Power" is not a crude desire for domination, but a fundamental drive to create, to excel, and to overcome oneself. Happiness, in this context, is not the absence of pain, but the feeling of power that comes from mastering challenges and forging one's own values, embracing the totality of life and death.

Modern Perspectives: Utility, Existence, and Well-being

The philosophical conversation surrounding pleasure and the good life continued to evolve through the Enlightenment and into the modern era, incorporating new scientific and social considerations.

Utilitarianism: The Greatest Happiness for the Greatest Number

The Utilitarian philosophers, notably Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, placed pleasure and pain at the center of their ethical systems. For Bentham, the moral worth of an action is determined by its ability to produce the greatest amount of happiness (understood as pleasure and the absence of pain) for the greatest number of people. Mill refined this, arguing for a distinction between "higher" intellectual pleasures and "lower" bodily pleasures, famously stating, "It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied." Utilitarianism thus attempts to quantify and maximize overall societal happiness, often requiring a careful calculation of consequences and the management of individual desires for the collective good.

Existentialism: Freedom, Responsibility, and Meaning-Making

In the 20th century, existentialist thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus challenged the notion of a predetermined "good life." They emphasized human freedom, radical responsibility, and the inherent meaninglessness of the universe. Pleasure is not the primary goal; rather, individuals are condemned to be free, to create their own values and meaning in an absurd world. Happiness, if it is to be found, comes from authentic living, embracing the anguish of freedom, and confronting the reality of life and death without illusion. The pursuit of pleasure alone, without a foundation of self-created meaning, is often depicted as a form of bad faith.

Positive Psychology: A Scientific Approach to Happiness

In recent decades, the field of positive psychology has emerged, offering a scientific, empirical approach to understanding happiness and well-being. Researchers like Martin Seligman have moved beyond merely treating mental illness to explore what makes life worth living. While acknowledging the role of pleasure, positive psychology emphasizes concepts like engagement, meaning, accomplishment, and positive relationships as key components of a flourishing life, echoing many of the virtues found in Aristotelian eudaimonia.

Navigating the Path: Integrating Pleasure, Virtue, and Purpose

The diverse philosophical perspectives on the pursuit of pleasure and the good life reveal that there is no single, universally accepted answer. However, recurring themes and insights offer guidance for navigating this complex terrain.

Here's a comparison of key approaches:

| Philosophical Approach | Primary Goal | View on Pleasure | View on Desire | Role of Pain | Key Figures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyrenaic Hedonism | Immediate bodily pleasure | The sole good | To be satisfied immediately | The sole evil | Aristippus |

| Epicureanism | Ataraxia (tranquility), Absence of pain | Absence of pain and disturbance | To be managed, simple desires preferred | To be avoided | Epicurus |

| Aristotelian Eudaimonia | Flourishing through virtuous activity | A natural accompaniment to virtue, not the goal | To be guided by reason and virtue | Can be overcome or endured for virtue | Aristotle |

| Stoicism | Apathy (indifference to externals), Virtue | Indifferent, not the goal | To be controlled, accept what is | Indifferent, to be endured | Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius |

| Utilitarianism | Greatest happiness for the greatest number | The ultimate good (quantity & quality) | To be managed for collective good | To be minimized for collective good | Bentham, Mill |

| Nietzschean Philosophy | Self-overcoming, Affirmation of life | A consequence of strength, not the goal | To be embraced and channeled (Will to Power) | Necessary for growth and overcoming | Nietzsche |

Ultimately, a truly good life often involves a delicate balance:

- Mindful Engagement with Pleasure: Enjoying the legitimate pleasures of life without becoming enslaved by them.

- Virtuous Action: Cultivating character traits that lead to flourishing, not just for oneself but for one's community.

- Purpose and Meaning: Identifying and pursuing goals that give direction and significance beyond immediate gratification.

- Resilience in the Face of Pain: Accepting that pain and suffering are inevitable parts of the human condition and can be sources of growth.

- Confronting Life and Death: Understanding our mortality not as a source of terror, but as a motivator to live authentically and make the most of our time.

The pursuit of pleasure, when unbridled, can lead to emptiness. When integrated with wisdom, virtue, and a sense of purpose, it can contribute to a life that is not only enjoyable but also deeply meaningful. The journey towards the good life is an ongoing philosophical endeavor, inviting each of us to reflect on our desires, our values, and our place in the grand scheme of life and death.

Further Exploration

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Epicurean philosophy summary" or "Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics explained""

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Schopenhauer will and suffering" or "Nietzsche will to power explained""