The Pursuit of Happiness and the Good Life: A Timeless Inquiry

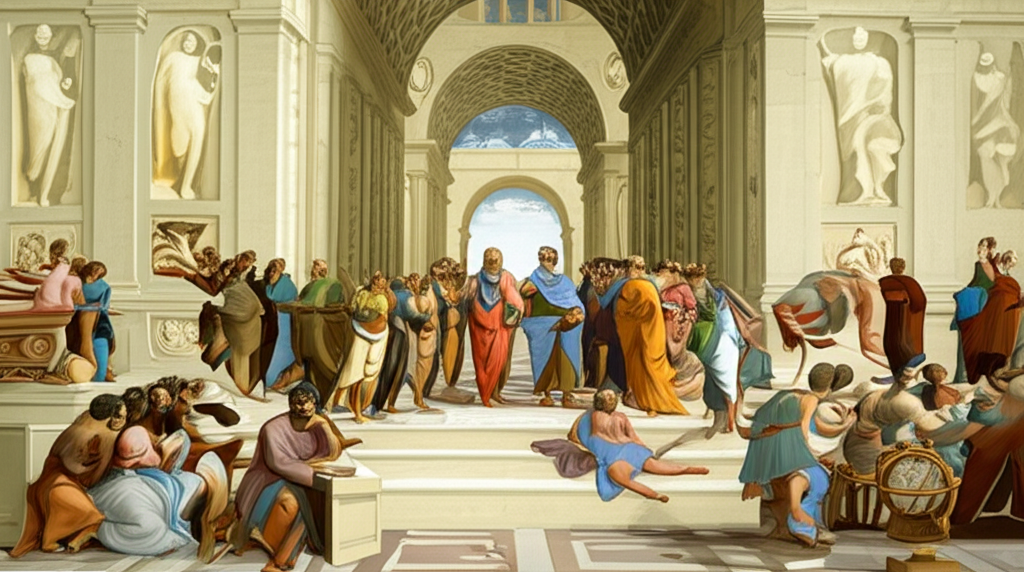

For millennia, humanity has grappled with two fundamental questions: What constitutes true happiness, and how does one live a good life? These are not mere academic exercises but deeply personal quests that define our existence. From the bustling agora of ancient Athens to the quiet contemplation of a medieval monastery, thinkers have sought to unravel the intricate relationship between our desires, our actions, and our ultimate well-being. This article delves into the rich tapestry of philosophical thought, particularly as presented in the Great Books of the Western World, to explore how different traditions have approached these enduring questions, distinguishing between fleeting pleasure and pain and the profound, lasting state of eudaimonia, and how our understanding of good and evil shapes our journey through life and death.

Beyond Mere Pleasure: Defining Eudaimonia

In contemporary society, "happiness" often connotes a transient feeling of joy or contentment, a state often sought through immediate gratification. However, the classical philosophical tradition, particularly that stemming from ancient Greece, offered a far more robust and enduring concept: eudaimonia. Often translated as "flourishing," "human flourishing," or "the good life," eudaimonia is not a fleeting emotion but a state of being achieved through virtuous activity, reason, and a life lived well.

Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, famously argued that happiness (eudaimonia) is the chief good, the ultimate end of human action. He contended that while pleasures are good, they are not the summum bonum. True happiness, for Aristotle, is an activity of the soul in accordance with virtue, over a complete life. It requires rational deliberation, ethical conduct, and the cultivation of character. It is a state earned, not simply felt.

The Spectrum of Experience: Pleasure, Pain, and Virtue

The relationship between pleasure and pain has always been central to the discussion of the good life. While some philosophies, like Hedonism (epitomized by Epicurus), posited that pleasure is the highest good and the absence of pain is the goal, they often distinguished between crude, fleeting pleasures and more refined, lasting contentment. Epicurus, for instance, advocated for a life of modest pleasures, tranquility (ataraxia), and freedom from fear, rather than excessive indulgence.

In contrast, the Stoics, such as Seneca and Marcus Aurelius, viewed pleasure and pain as "indifferents" – things that do not inherently contribute to or detract from the good life. For them, true happiness lay in virtue, reason, and living in accordance with nature, accepting what cannot be changed, and exercising control over one's internal reactions. A virtuous person could find inner peace regardless of external circumstances, including physical discomfort or misfortune.

Comparative Views on Pleasure and Happiness:

| Philosophical School | Primary Goal | View on Pleasure | View on Pain | Path to Happiness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aristotelian | Eudaimonia (Flourishing) | A natural accompaniment to virtuous activity, but not the goal itself. | Can hinder virtuous activity, but not determinative of happiness. | Virtuous activity, rational deliberation, character development. |

| Epicurean | Ataraxia (Tranquility) | The highest good, especially the absence of pain and mental disturbance. | To be avoided; a primary obstacle to happiness. | Simple living, friendship, philosophical contemplation, freedom from fear. |

| Stoic | Virtue (Reason) | An "indifferent"; neither good nor bad in itself. Not to be pursued. | An "indifferent"; to be accepted with equanimity. Not to be avoided. | Living in accordance with reason and nature, cultivating inner virtue, control over reactions. |

Navigating the Moral Landscape: Good and Evil

The pursuit of the good life is inextricably linked to our understanding of good and evil. What we deem "good" often directs our actions, while what we perceive as "evil" guides our avoidance. Plato, in works like The Republic, argued that the good life is one lived in accordance with justice and reason, where the individual soul mirrors the ideal state. For him, true good was objective, an eternal Form that enlightened the mind and guided moral action. To know the Good was to do the Good.

Christian philosophy, as articulated by thinkers like Augustine and Aquinas, integrated classical ideas with theological concepts. The ultimate good became union with God, and happiness was seen as a beatific vision, a state of perfect contentment found in divine love and grace. Evil, in this framework, was often understood as a privation of good, a turning away from God, rather than an inherent force. The path to the good life thus involved faith, charity, and adherence to divine law.

The Shadow of Mortality: Life and Death

The finite nature of our existence – the certainty of life and death – profoundly shapes our philosophical inquiries into happiness and the good life. The awareness of mortality can imbue our choices with urgency and meaning. For many ancient philosophers, contemplating death was not morbid but a crucial exercise in living well. Socrates famously stated that "the unexamined life is not worth living," and his calm acceptance of his own death, as recounted in Plato's Phaedo, served as a powerful testament to a life lived in accordance with virtue and philosophical principle.

The Stoics, too, advocated for memento mori – remembering that one must die. This awareness was meant to foster appreciation for the present moment, reduce anxiety over trivial matters, and encourage living a life of purpose and virtue, unburdened by fear of the inevitable. It reminds us that the "good life" is not merely about accumulating experiences or possessions, but about cultivating character and contributing meaningfully within the limited time we have.

Conclusion: An Ongoing Dialogue

The pursuit of happiness and the good life remains a central human endeavor, a perpetual philosophical journey that transcends cultures and epochs. While the specifics of what constitutes this ideal may vary – from Aristotle's virtuous activity to Epicurus's tranquility, from the Stoic's reasoned acceptance to the Christian's divine love – the underlying quest for meaning, purpose, and flourishing endures. The Great Books of the Western World offer not definitive answers, but a rich, ongoing dialogue, inviting each of us to examine our own lives, reflect on our values, and consciously strive towards a life that is not merely lived, but lived well.

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics Eudaimonia Explained""

📹 Related Video: STOICISM: The Philosophy of Happiness

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Stoicism and the Art of Living a Good Life""