The Inner Tempest: Unpacking the Psychological Basis of Emotion

The human mind, a boundless theatre of thought and sensation, finds itself perpetually navigating the powerful currents of emotion. From the serene calm of contentment to the tempestuous surges of rage, these profound internal states form an undeniable bedrock of the human experience. This article delves into the rich philosophical tradition, drawing from the Great Books of the Western World, to explore the psychological basis of emotion. We will examine how seminal thinkers conceived of its origins, its intricate relationship to reason, and its fundamental role in shaping the life of Man, often touching upon the very physics of existence—the interplay between the material and the immaterial—that informs our comprehension of our affective lives.

The Classical Labyrinth: Ancient Insights into the Soul's Stirrings

For centuries, philosophers have wrestled with the nature of emotion, seeking to categorize, understand, and, often, master these powerful internal forces. Their inquiries laid the groundwork for what we now understand as the psychological study of emotion.

Plato's Tripartite Soul and the Charioteer

In the philosophical landscape of ancient Greece, Plato offered a compelling model for understanding the soul and, by extension, the origins of emotion. In his Republic and Phaedrus, he famously posited the soul as tripartite, composed of:

- Reason (Logistikon): The rational, calculating part, seeking truth and wisdom, akin to the charioteer.

- Spirit (Thymoeides): The spirited, courageous, and honor-loving part, capable of noble anger or righteous indignation, one of the horses.

- Appetite (Epithymetikon): The desiring, pleasure-seeking part, driven by hunger, thirst, and carnal desires, the other horse.

Plato viewed many emotions as arising from the spirited and appetitive parts of the soul. The challenge for Man was to allow Reason, the charioteer, to guide and harmonize these powerful, often conflicting, forces. A lack of such guidance led to internal discord and emotional excess, demonstrating an early understanding of emotional regulation as a philosophical imperative.

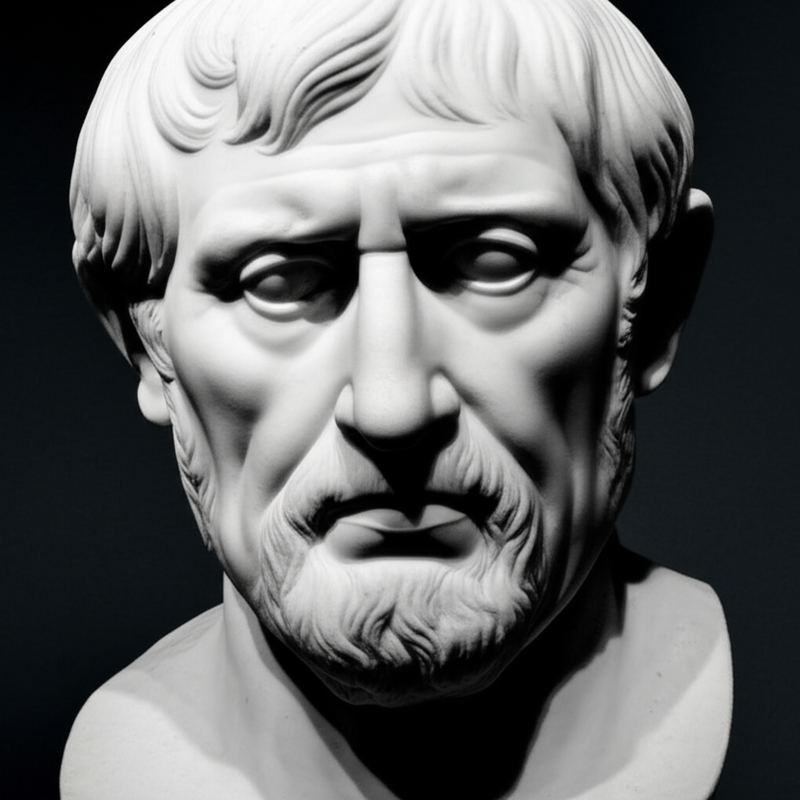

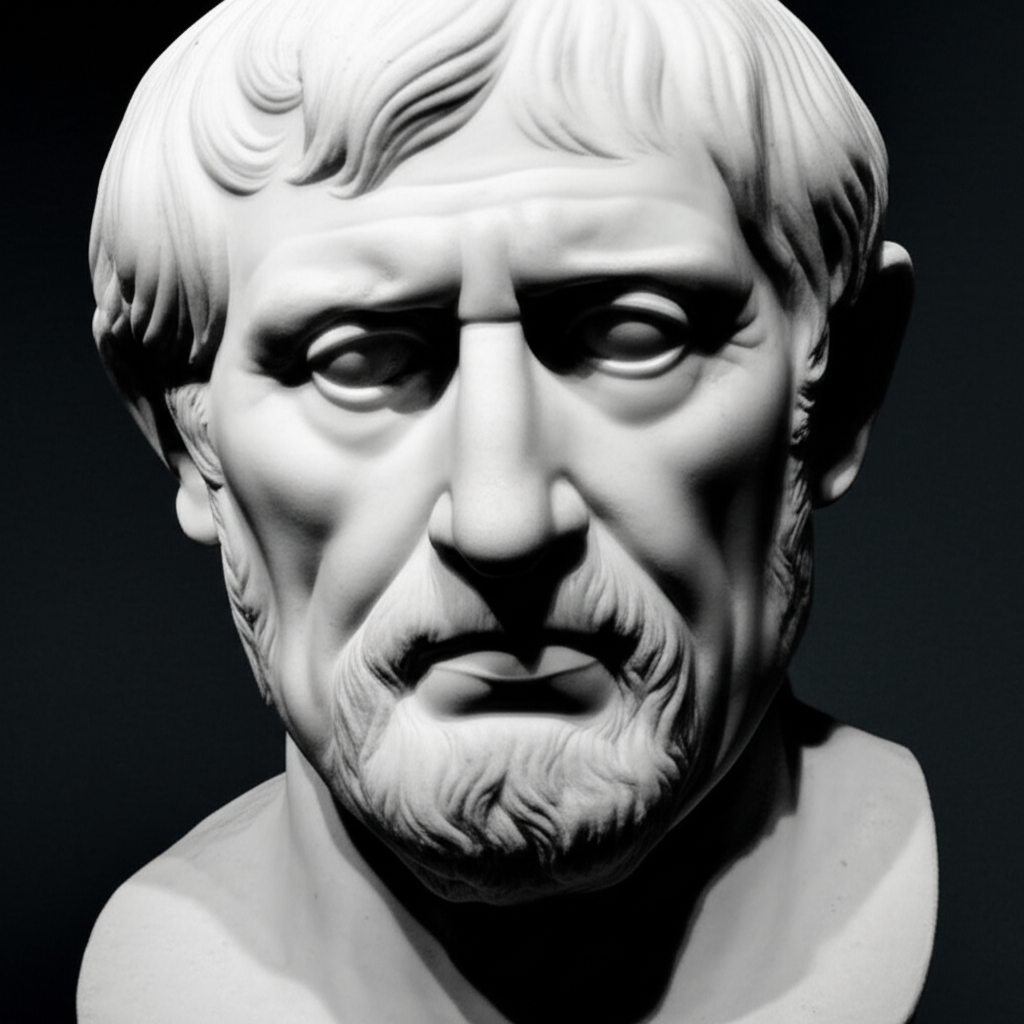

Aristotle's Ethics and the Habituation of Feeling

Aristotle, Plato's most famous student, offered a more nuanced and integrated view of emotion, particularly in his Nicomachean Ethics. For Aristotle, emotions were not merely disruptive forces to be suppressed but integral components of a virtuous life. He recognized that feeling emotions appropriately—at the right time, towards the right objects, for the right reasons, and in the right degree—was crucial for eudaimonia, or human flourishing.

He emphasized the role of habituation in shaping our emotional responses. Virtue, for Aristotle, was a disposition, a state of character, that allowed Man to feel and act well. This involved:

- Perceiving the situation correctly: Understanding the context and implications.

- Feeling the appropriate emotion: Not too much, not too little, but the "mean."

- Acting accordingly: Letting reason guide the expression of emotion into virtuous action.

Thus, for Aristotle, the psychological basis of emotion was deeply intertwined with ethical development, where emotions could be cultivated and refined through practice and rational reflection.

The Mind-Body Conundrum: The Physics of Feeling and the Soul

With the advent of the modern philosophical era, the focus shifted, bringing the intricate relationship between the mind and the physical body—the physics of our being—into sharp relief when discussing emotion.

Descartes and the Passions of the Soul

René Descartes, a pivotal figure in the 17th century, famously articulated a dualistic view, separating the thinking substance (mind/soul) from the extended substance (body). In his Passions of the Soul, he sought to explain how these two distinct entities could interact, giving rise to emotions.

For Descartes, passions (his term for emotions) were perceptions, sensations, or commotions of the soul that are referred to it, and are caused, maintained, and strengthened by some movement of the spirits. These "spirits" were subtle, quickly moving particles within the blood, influencing the pineal gland, which Descartes believed was the seat of mind-body interaction.

This view introduced a mechanistic, almost physical, explanation for the psychological experience of emotion:

- External stimulus: A sensory input from the world.

- Physical reaction: The body responds, circulating "spirits."

- Soul's perception: The soul perceives these bodily commotions as passions.

While controversial, Descartes' work highlighted the physiological underpinnings of emotion and sparked intense debate about the mind-body problem, a core aspect of understanding the physics of emotion.

Spinoza's Monism and the Mechanics of Affect

Baruch Spinoza, a contemporary of Descartes, presented a radical alternative in his Ethics, asserting a monistic view where mind and body are not distinct substances but merely two attributes of a single substance: God, or Nature. For Spinoza, emotions, which he called "affects," were not disruptions of the soul but natural phenomena, subject to the same deterministic laws as any other physical event.

Spinoza's approach was akin to a physics of the mind, where affects arise from the interaction between an individual's conatus (the striving to persevere in one's being) and external causes.

| Emotion (Affect) | Spinoza's View | Connection to Physics/Mechanics |

|---|---|---|

| Joy | An increase in the mind's and body's power of acting. | Analogous to a system gaining energy or momentum. |

| Sadness | A decrease in the mind's and body's power of acting. | Analogous to a system losing energy or momentum. |

| Desire | The very essence of Man in so far as it is conceived as determined to act in a given way. | The inherent force or tendency driving a system. |

For Spinoza, true freedom lay not in suppressing emotions, but in understanding their causal necessity through reason. By grasping the mechanics of our affects, Man could transition from passive suffering to active understanding, thereby increasing his power and freedom.

The Enduring Quest: Emotion, Reason, and the Integrated Man

The journey through the Great Books reveals a consistent thread: the human struggle to understand and integrate emotion within a coherent view of the self. From Plato's charioteer to Spinoza's affects, philosophers have sought to map the internal landscape of the mind, recognizing that our emotional lives are not merely peripheral experiences but central to our identity, our moral choices, and our quest for meaning.

Later thinkers, building on these foundations, continued to explore the complex interplay between reason and feeling, moving beyond simple dualisms towards a more holistic understanding of Man. The psychological basis of emotion, therefore, is not a static concept but a dynamic field of inquiry, continually enriched by philosophical reflection and scientific discovery. It reminds us that to truly know ourselves is to understand the intricate dance between thought and feeling, and to recognize the profound influence these inner tempests have on our outer world.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato's Chariot Allegory explained philosophy"

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Spinoza Ethics on Emotions explained"