The Architectures of Feeling: Unpacking the Psychological Basis of Emotion

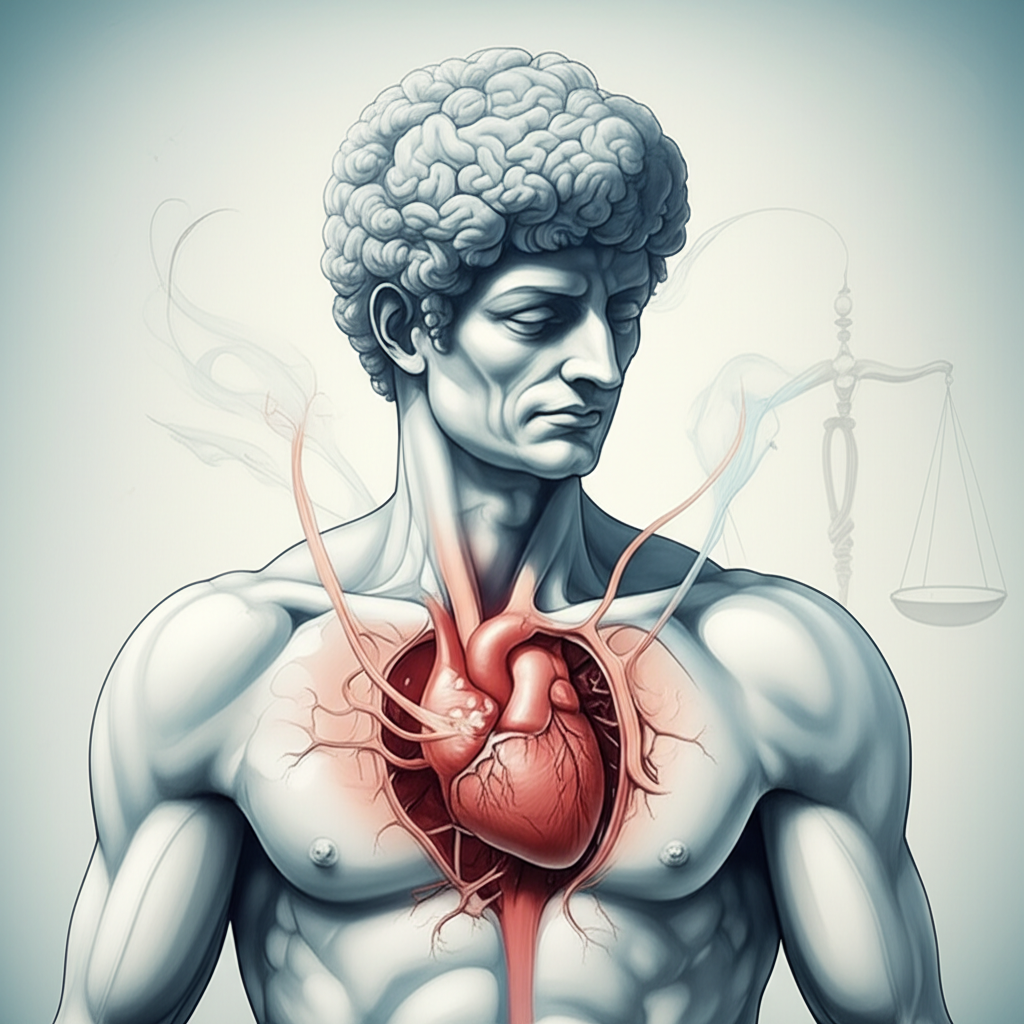

Summary: The essence of human emotion has perplexed thinkers from antiquity, lying at the very heart of what it means to be Man. This article traverses the philosophical landscape, drawing from the Great Books of the Western World, to explore the psychological underpinnings of our feelings. From Plato's tripartite soul to Descartes' mechanical mind, and even touching upon the subtle influence of physics in understanding our bodily states, we uncover how various epochs have grappled with the genesis of joy, sorrow, anger, and love, ultimately revealing a continuous quest to comprehend the intricate dance between our inner world and the external cosmos.

The Unfolding Tapestry of Human Emotion

To speak of emotion is to touch upon the very core of human experience. It is the vibrant, often tumultuous, landscape within the mind of Man, shaping his perceptions, driving his actions, and defining his relationships. Yet, the precise mechanisms by which these powerful feelings arise, how they are processed, and their ultimate purpose, have remained subjects of profound philosophical inquiry for millennia. What is the psychological basis of these affections that so profoundly colour our existence? Is it purely a function of the immaterial mind, or are its roots deeply embedded in the physics of our corporeal being?

I. The Ancient Gaze: Passions, Virtue, and the Soul's Harmony

Long before the advent of neuroscience, ancient philosophers, particularly those whose wisdom is preserved in the Great Books, sought to understand emotion not merely as fleeting states but as integral components of the soul's architecture.

-

Plato's Tripartite Soul: In works like The Republic and Phaedrus, Plato posited a soul divided into three parts:

- Reason (λογιστικόν): The charioteer, guiding the soul towards truth.

- Spirit (θυμοειδές): The noble steed, associated with courage, honour, and righteous indignation—the wellspring of many strong emotions.

- Appetite (ἐπιθυμητικόν): The unruly steed, driven by desires for food, drink, and carnal pleasure, also a source of powerful emotions like lust and greed.

For Plato, the psychological basis of emotion lay in the dynamic interplay and potential conflict between these parts. Harmony, achieved when reason governs the spirited and appetitive parts, was the path to virtue and inner peace for Man.

-

Aristotle's Empirical Approach: Aristotle, in De Anima and Nicomachean Ethics, offered a more empirical and less dualistic view. He saw emotions (πάθη - pathē) as psychophysical phenomena—states of the soul that are inseparable from bodily changes. For instance, he defined anger as "a boiling of the blood about the region of the heart." Here, the nascent concept of physics intertwines with psychology: the physical state of the body directly influences, and is indeed part of, the emotional experience. Aristotle argued that emotions are not inherently good or bad, but become so through their application and measure. The virtuous Man experiences the right emotion, at the right time, towards the right object, and to the right degree.

-

The Stoic Ideal: For the Stoics, particularly Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, emotions were often seen as distortions of reason, or "passions" (pathē), arising from false judgments about what is good or bad. Their psychological aim was apatheia—not apathy in the modern sense, but freedom from disturbances, achieved by understanding what is within our control (our judgments) and what is not (external events). The psychological basis here is cognitive: change your judgment, change your emotion.

II. Descartes and the Mechanical Man: A Mind-Body Conundrum

The dawn of modern philosophy brought new perspectives, particularly with René Descartes, whose work laid the groundwork for the mind-body problem that continues to echo in our understanding of emotion.

Descartes, in Passions of the Soul, attempted to explain how the immaterial mind interacts with the material body. He described emotions or "passions" as perceptions, sensations, or commotions of the soul, "referred to it especially as it is in union with the body." The physics of the body—specifically the movement of "animal spirits" through the nerves and into the brain—was believed to cause these passions. The pineal gland, a small organ in the brain, was proposed as the principal seat where the soul (the mind) directly exercised its functions and received impressions from the body.

This marked a crucial shift: while ancient thinkers often integrated body and mind, Descartes sharply separated them, then struggled to reunite them in the context of emotion. The psychological basis here is a two-way street, where physical stimuli (the physics of the body) trigger mental perceptions that are then experienced as emotions.

III. Empiricism and the Primacy of Experience

The British Empiricists offered another lens through which to view the psychological basis of emotion, emphasizing experience and sensation.

-

John Locke: In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Locke argued that all knowledge and ideas come from either sensation or reflection. Emotions, for Locke, are complex ideas derived from these basic experiences, built upon simple ideas of pleasure and pain. The mind processes sensory input, and these processed ideas evoke emotional responses.

-

David Hume: Perhaps the most radical in his assessment of emotion, David Hume famously declared in A Treatise of Human Nature that "Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them." For Hume, emotions are primary, irreducible impressions that drive human action. Reason's role is merely to find the most efficient means to achieve the ends dictated by our feelings. The psychological basis here is not rational control but the inherent force of these passions within the man.

IV. Modern Echoes: Bridging Brain and Mind

While the Great Books provide the foundational philosophical inquiries, contemporary science, particularly neuroscience, has offered profound insights into the physics of the brain and its role in emotion. Modern understanding often seeks to bridge the Cartesian gap, viewing the mind and its emotional life as emergent properties of complex neural networks.

Today, the psychological basis of emotion is often explored through the lens of evolutionary biology, cognitive science, and affective neuroscience. We speak of amygdala activation, neurotransmitter release, and neural circuits. Yet, the fundamental philosophical questions persist: How do these physical processes translate into the subjective experience of feeling? Is emotion merely a biochemical reaction, or does the mind imbue it with a deeper, perhaps ineffable, meaning?

Consider the progression of thought:

| Aspect of Emotion | Ancient Philosophical View (e.g., Plato, Aristotle) | Modern Scientific View (e.g., Neuroscience) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin/Basis | Tripartite soul, bodily humors, rational judgment, vital spirits (early physics) | Brain structures (amygdala, prefrontal cortex), neurochemicals, evolutionary drives |

| Nature of Experience | Psychophysical, often tied to virtue or vice, moral implications, subjective | Subjective, but with measurable physiological correlates, adaptive functions |

| Role in Human Life | Integral to virtue, motivator of action, source of conflict/harmony for the man | Motivator, social bonding, survival mechanism, influences cognition and decision-making |

| Mind-Body Relationship | Often integrated (Aristotle), or dualistic with interaction (Plato, early Descartes) | Emergent property of the brain, complex interaction, often seen as inseparable |

V. The Enduring Question: The Man and His Feelings

From the ancient Greek philosophers striving for a harmonious soul, through the meticulous anatomical inquiries of Descartes, to the empiricists grounding emotion in raw experience, and now to the intricate mapping of neural pathways, the quest to understand the psychological basis of emotion remains central to understanding Man.

The Great Books of the Western World remind us that while our tools and terminology evolve, the fundamental questions about the mind's architecture, the influence of our physical being (our internal physics), and the essence of emotion itself, are perennial. To truly comprehend Man is to delve into the depths of his feelings, recognizing that they are not mere ephemeral states, but profound expressions of his existence.

YouTube Suggestions:

- YouTube: "Philosophy of Emotion Plato Aristotle"

- YouTube: "Descartes Passions of the Soul explained"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Psychological Basis of Emotion philosophy"