The Problem of Sin and Desire: A Philosophical Inquiry

The human condition is perennially entangled in a profound philosophical knot: the Problem of reconciling our innate Desires with the concept of Sin. This tension, a central theme across the Great Books of the Western World, forces us to confront fundamental questions about Good and Evil, freedom, responsibility, and the very nature of human flourishing. From ancient Greek contemplation of appetites to Christian doctrines of fallen will and modern existentialist critiques, the struggle to understand why we often pursue what we know to be wrong, or what is deemed "sinful," despite our capacity for reason, remains one of philosophy's most enduring challenges.

The Enduring Conundrum: Defining the Terms

At the heart of this Problem lies a definitional challenge. What, precisely, do we mean by "desire" and "sin"?

- Desire: In its broadest sense, desire is a fundamental aspect of life—the impetus for action, growth, and survival. It encompasses everything from basic biological urges (hunger, thirst) to complex psychological yearnings (for love, knowledge, power, recognition). Philosophically, desire is often seen as a driving force, but one that can be either virtuous or destructive depending on its object and regulation.

- Sin: The concept of sin typically denotes an offense against a divine law, a moral principle, or a natural order. It implies a transgression, a falling short, or a deliberate act against what is considered good. While deeply rooted in theological traditions, philosophy grapples with sin as a moral failing, an act contrary to reason, or an impediment to human flourishing, irrespective of explicit divine command.

The Problem arises when these two forces collide: when our desires, left unchecked or misdirected, lead us down paths deemed sinful, or when the very act of desiring is seen as a source of moral corruption.

Ancient Roots: Desire as a Double-Edged Sword

Long before the explicit concept of sin as a theological transgression, ancient philosophers grappled with the unruly nature of desire and its potential to lead humans astray from good.

Plato's Charioteer: Reason vs. Appetite

In Plato's Phaedrus, the famous allegory of the charioteer illustrates the internal struggle. The soul is likened to a charioteer (reason) guiding two winged horses: one noble and well-behaved (spirit/will), and the other unruly and impetuous (appetite/desire). For Plato, true virtue and harmony are achieved when reason effectively controls and directs the appetitive desires. Unchecked desire leads to imbalance, chaos, and a failure to ascend towards the Forms of Good. While not using the term "sin," Plato clearly identifies the problem of appetitive desire overriding reason as a fundamental flaw in human conduct.

Aristotle's Golden Mean: Desire Guided by Virtue

Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, offers a more nuanced view. Desire itself is not inherently bad; rather, it is how and to what extent we act upon our desires that determines moral character. Virtue, for Aristotle, lies in finding the "golden mean" between excess and deficiency. For instance, the desire for pleasure is natural, but gluttony (excess) and insensibility (deficiency) are vices. The virtuous person, guided by practical wisdom (phronesis), knows how to properly direct their desires towards good ends, acting at the right time, in the right way, for the right reasons. A failure to do so, a deviation from the mean, constitutes a moral failing, akin to what later traditions would call sin.

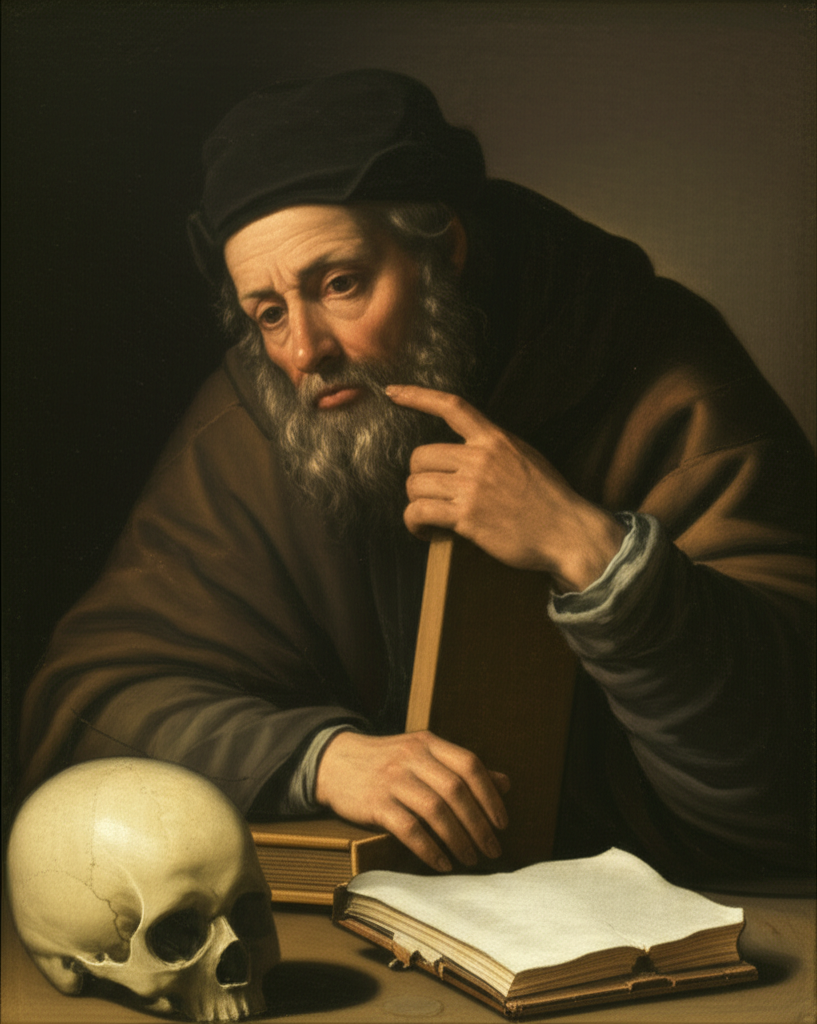

The Christian Turn: Sin's Definitive Entry

With the rise of Christianity, particularly through the writings of St. Augustine, the Problem of sin and desire takes on a distinctly theological and existential dimension.

Augustine's Concupiscence: The Burden of Original Sin

St. Augustine of Hippo, profoundly influenced by his own struggles detailed in Confessions, articulated a powerful doctrine of Original Sin. For Augustine, humanity inherited a fallen nature from Adam, characterized by concupiscence—a disordered desire or inclination towards worldly pleasures and away from God. This is not merely a weakness but a fundamental corruption of the will, making it prone to sin. Even good desires can be tainted if they are not ultimately directed towards God. The problem here is not just individual acts of sin, but a pervasive inclination to sin itself, rooted in our very being.

Aquinas: Sin as a Deviation from Reason and Divine Law

St. Thomas Aquinas, building on Aristotle and Augustine in his Summa Theologica, systematized the concept of sin. He defined sin as an act, word, or desire contrary to the eternal law and human reason. For Aquinas, human beings are naturally inclined towards the good, but through ignorance, passion, malice, or weakness, our desires can lead us to choose a lesser good over the true good, thus committing sin. The intellect's failure to properly guide the will, often swayed by intense desire, is a key mechanism of sin.

Enlightenment and Beyond: Re-evaluating Desire and Morality

The Enlightenment brought a re-evaluation of human autonomy and reason, shifting the focus from divine law to human moral agency, yet the problem persisted.

Kant's Categorical Imperative: Duty Over Desire

Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Practical Reason, radically separated morality from desire. For Kant, true moral action arises not from inclination or desire (which he saw as heteronomous and contingent) but from a pure sense of duty, dictated by the Categorical Imperative. An action is moral only if it is done from duty, not merely in accordance with duty. To act based on desire, even for a good outcome, is not truly moral. Sin, in a Kantian sense, would be to act against the universal moral law discernible by reason, prioritizing personal inclination over rational duty.

Nietzsche's Revaluation: Beyond Good and Evil

Friedrich Nietzsche offered a radical critique of traditional morality, particularly the Judeo-Christian concepts of sin and good and evil. In On the Genealogy of Morality, he argued that these concepts were inventions of the weak to control the strong, a "slave morality" that demonized natural human desires and instincts (the "will to power"). For Nietzsche, what was traditionally called "sin" or "evil" might actually be expressions of vitality and strength. He challenged the very foundation of the problem by suggesting that the moral categories used to define sin and constrain desire were themselves problematic.

The Interplay: When Desire Becomes Sinful

The core of the problem lies in the complex interplay between our inherent drives and the moral frameworks we impose. Is desire itself the root of sin, or merely the raw material that, when mismanaged, leads to sinful acts?

Most philosophical traditions agree that desire is not inherently sinful. It is the object of desire, the intensity of desire, or the unregulated pursuit of desire that can lead to sin.

Here's a simplified view of how different traditions perceive this relationship:

| Philosophical Tradition | View on Desire | View on Sin | Interplay |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platonism | Appetitive force, needs rational control. | Imbalance, disharmony of the soul, failure to achieve virtue. | Unchecked desire leads to the soul's disharmony, preventing the pursuit of Good. |

| Aristotelianism | Natural, but requires moderation and guidance. | Deviation from the virtuous mean, acting against reason. | Desire, when not guided by practical wisdom, can lead to excess or deficiency, resulting in moral vice. |

| Augustinianism | Disordered, concupiscent due to Original Sin. | Innate inclination to offend God, acts against divine will. | Fallen human nature means desire is inherently tainted, leading inevitably to sin without divine grace. |

| Thomism | Natural, but can be swayed by passion/ignorance. | Act contrary to reason and divine law. | Desire can overshadow reason, leading the will to choose a lesser good over the true good, thus committing sin. |

| Kantianism | Inclination, heteronomous, not basis for morality. | Acting against the Categorical Imperative, duty. | Moral action must transcend desire; acting from desire is not truly moral, and acting against duty due to desire is sinful. |

Contemporary Reflections and Conclusion

The Problem of Sin and Desire continues to resonate in modern thought. While secular philosophies might eschew the term "sin," they still grapple with the phenomena of self-destructive urges, moral failings, and the struggle for self-control. Existentialists, for instance, might speak of bad faith or inauthenticity as a failure to embrace one's freedom and responsibility, often driven by the desire to escape anxiety. Psychology explores the roots of addiction, impulsivity, and antisocial behavior, often finding parallels to the ancient problem of uncontrolled desire.

Ultimately, the philosophical journey through the Problem of Sin and Desire reveals a persistent human struggle. Our desires are integral to who we are, driving us towards creation and connection, but also tempting us towards destruction and transgression. The ongoing quest for good involves understanding, managing, and often transcending these powerful internal forces, constantly navigating the complex landscape of Good and Evil within ourselves and the world.

YouTube: philosophy of desire Augustine

YouTube: Kant duty vs inclination explained

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Problem of Sin and Desire philosophy"