The Unseen Leap: Confronting the Problem of Induction in Scientific Discovery

For all its triumphs, its ability to unravel the universe's deepest secrets, science rests upon a foundation that, upon closer inspection, reveals a curious and persistent logical chasm. This is the Problem of Induction, a philosophical conundrum that challenges the very basis of how we derive knowledge from experience. In essence, it asks: how can we justify believing that the future will resemble the past, or that observed regularities will continue indefinitely? This article delves into this fundamental challenge, exploring its historical roots and its profound implications for scientific understanding.

The Problem of Induction: A Summary

The Problem of Induction highlights the logical gap between observing a finite number of instances and drawing a universal conclusion. While induction is the cornerstone of scientific method – observing many swans are white, then concluding all swans are white – there's no inherent logical necessity that the next swan observed will also be white. This isn't a mere quibble; it questions the rational basis for all empirical prediction and generalization, suggesting that our most robust scientific "laws" are, at their core, acts of faith in the uniformity of nature, rather than strictly demonstrable truths.

The Pillars of Scientific Inquiry and the Inductive Leap

From the earliest observations of celestial bodies to the most sophisticated experiments in quantum physics, science progresses by identifying patterns and formulating general principles. When a physicist conducts an experiment multiple times and observes the same outcome, they induce a general law. When a biologist observes a particular species for years and notes consistent behaviours, they generalize about that species' characteristics. This process, moving from specific observations to general conclusions, is induction.

Consider these common inductive leaps in scientific practice:

- Gravity: Observing countless objects fall to Earth leads to the inductive conclusion that gravity always acts in this way.

- Chemical Reactions: Repeatedly mixing specific chemicals under certain conditions yields predictable results, leading to generalized chemical laws.

- Biological Processes: Observing consistent cellular functions across many organisms informs our understanding of universal biological principles.

Without induction, scientific progress as we know it would grind to a halt. We would be left with a collection of isolated facts, unable to form theories, make predictions, or build upon past discoveries.

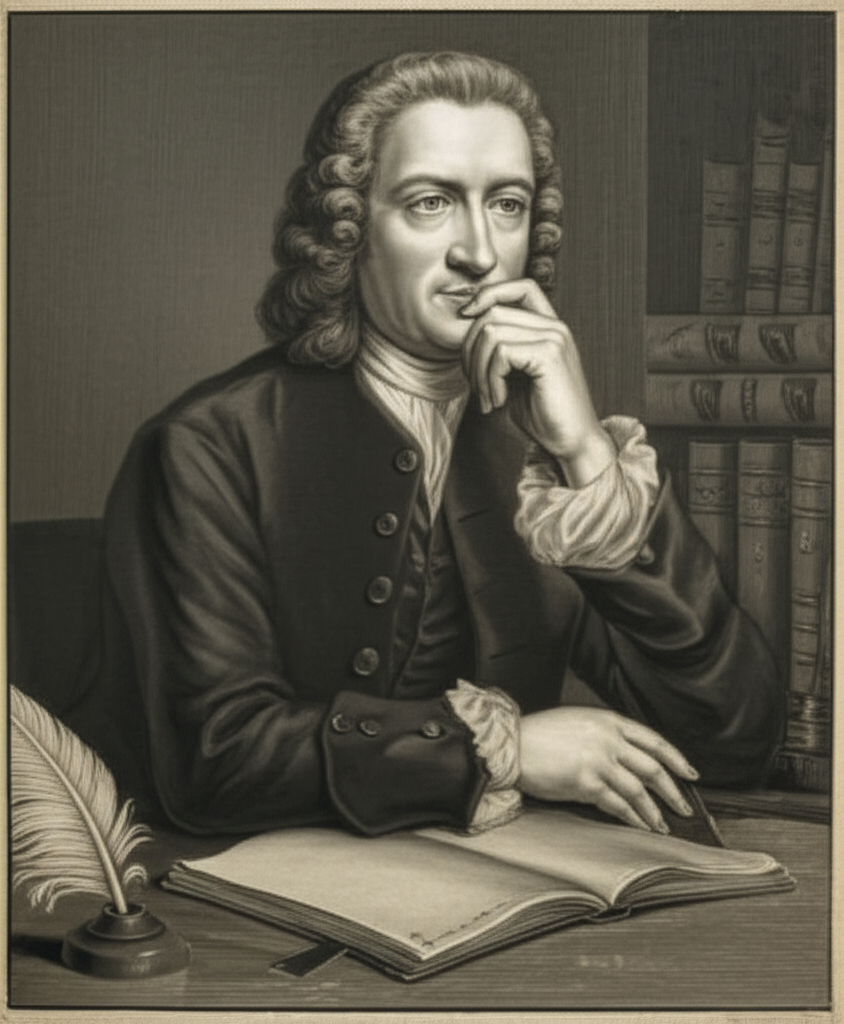

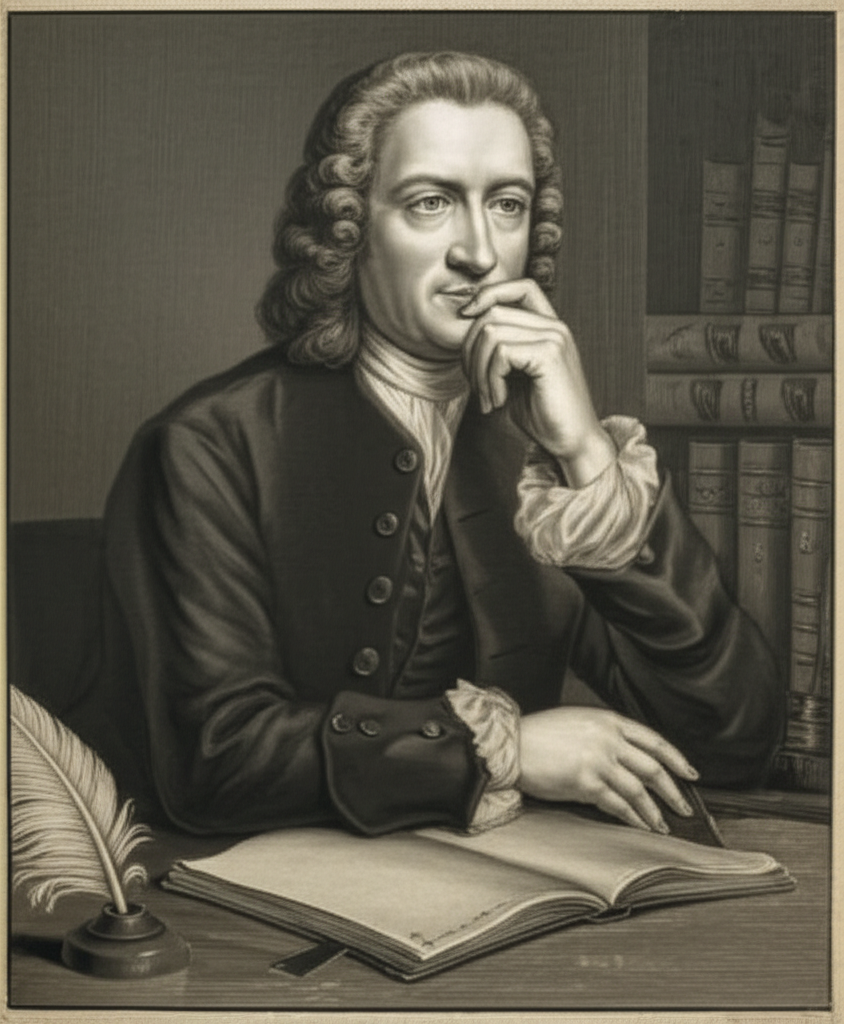

Hume's Skeptical Hammer: Unveiling the Logical Flaw

The most incisive articulation of the Problem of Induction comes from the Scottish philosopher David Hume, prominently discussed in the Great Books of the Western World. In his An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, Hume meticulously dissects the nature of our reasoning about matters of fact. He argues that all our beliefs about cause and effect, and indeed about the future, are founded not on logic or reason, but on custom or habit.

Hume's argument can be summarized as follows:

- All reasoning concerning matters of fact is based on the relation of cause and effect. We believe the sun will rise tomorrow because it has always risen in the past, implying a causal link.

- Our knowledge of cause and effect is derived entirely from experience. We don't deduce that fire burns by pure reason; we learn it by observing fire and its effects.

- Experience only tells us what has been observed, not what must be observed. We have seen the sun rise every day, but this doesn't logically guarantee it will rise tomorrow.

- To argue that the future will resemble the past (the "principle of the uniformity of nature") is itself an inductive inference. We assume uniformity because it has been uniform in the past. This creates a circular argument: we justify induction by appealing to induction.

This is the crux of the problem: there is no non-circular logical justification for believing in the uniformity of nature. Our expectation that the laws of physics will hold tomorrow is not a logical necessity but a psychological one, born from repeated observation. This insight rocked the foundations of knowledge and reason.

Responding to the Inductive Challenge

Philosophers and scientists have grappled with Hume's challenge for centuries. Several approaches have been proposed:

- Pragmatic Justification: Some argue that while induction might not be logically justifiable, it is pragmatically indispensable. We have no better method for making predictions and building knowledge. Even if it's not logically sound, it works.

- Falsificationism (Karl Popper): Karl Popper, another key figure in the philosophy of science, offered a different perspective. He argued that science doesn't primarily prove theories through induction, but rather disproves them through deduction. A scientific theory is one that can be falsified. We don't try to prove that all swans are white; we look for a black swan. If we find one, the theory is falsified. If we don't, the theory is corroborated, but never definitively "proven" in an inductive sense. This shifts the focus from verification to refutation.

- Bayesian Induction: More modern approaches use probability theory to assign degrees of belief to hypotheses based on evidence. While still relying on assumptions about prior probabilities, Bayesian methods offer a sophisticated framework for updating beliefs in light of new data.

Despite these attempts, the fundamental logical gap identified by Hume persists. The problem isn't about whether science works – it demonstrably does – but about the rational justification for why we trust its inductive leaps.

The Enduring Dilemma for Scientific Knowledge

The Problem of Induction serves as a powerful reminder of the inherent limitations and assumptions underlying our pursuit of knowledge. It forces us to confront the fact that even our most robust scientific theories are, in a profound sense, provisional. They are our best explanations so far, based on observed regularities, but they are not immune to future disconfirmation.

This isn't to say science is baseless or unreliable. Rather, it encourages a healthy intellectual humility. It highlights that the success of the scientific method is not a testament to the ironclad logic of induction, but perhaps to the remarkable, and fortunate, consistency of the natural world – a consistency we assume rather than prove. The Problem of Induction thus remains a vital philosophical touchstone, ensuring that we never take the foundations of our scientific understanding for granted.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""David Hume Problem of Induction Explained""

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Karl Popper Falsification vs Induction""