The Enduring Dance: Unpacking the Physics of Matter and Form

Isn't it fascinating how the deepest questions about reality often circle back to the simplest observations? We look at a tree, a rock, a human, and intuitively grasp that they are distinct, yet all exist. But what makes them what they are? This question, fundamental to what we now call Physics, has captivated thinkers for millennia. From the ancient Greeks, who first grappled with the very Element of existence, to modern scientists probing the subatomic realm, the interplay between Matter and Form remains a cornerstone of understanding. This article delves into how philosophy, particularly as explored in the Great Books of the Western World, illuminated this intricate relationship, offering insights that continue to resonate today.

The Quest for the Primal Element: Early Philosophical Physics

Before modern Physics gave us quarks and leptons, ancient philosophers embarked on a remarkable journey to uncover the fundamental Element of the cosmos. They observed the world, its changes, its stability, and sought a single, underlying principle or substance from which everything else derived. This was, in essence, their initial foray into the Physics of nature (physis).

- Thales of Miletus: Famously proposed water as the primary Element, observing its pervasive presence in life and its ability to transform.

- Anaximander: Disagreed, suggesting an undefined, boundless substance he called the apeiron, arguing that no single observable Element could contain all others without being consumed.

- Heraclitus: Championed fire, not just as a substance, but as a symbol of constant change and flux, emphasizing the dynamic nature of reality.

- Empedocles: Synthesized earlier ideas, positing four root Elements: earth, air, fire, and water, which combined and separated through the forces of Love and Strife to create all things.

These early inquiries, while perhaps seeming quaint by today's scientific standards, laid the groundwork for thinking systematically about the matter of the universe and the processes that give it form.

Plato's Realm of Forms: The Blueprint of Being

Stepping beyond the material Elements, Plato introduced a revolutionary concept: the Theory of Forms. For Plato, the visible world we perceive is merely a shadow, an imperfect copy, of a more real and perfect realm of Forms. These Forms are eternal, unchanging, and ideal blueprints for everything that exists.

- A beautiful painting is beautiful because it participates in the universal Form of Beauty.

- A specific tree is a tree because it partakes in the Form of Tree.

In Plato's view, the Form is what gives an object its essential nature, its identity. The physical matter of the world is always in flux, imperfect and perishable, but the Form it imperfectly embodies is immutable. This separation posited a profound dualism, suggesting that true knowledge lay not in studying the changing physical world, but in apprehending these perfect, intelligible Forms.

Aristotle's Hylomorphism: The Indivisible Duo of Matter and Form

It was Plato's student, Aristotle, who offered perhaps the most comprehensive and influential philosophical account of Matter and Form, a concept known as hylomorphism (from Greek hyle for matter and morphe for form). Unlike Plato, Aristotle argued that Matter and Form are not separate entities existing in different realms. Instead, they are inherent components of every physical substance.

For Aristotle, every individual thing in the world is a composite of:

- Matter (hyle): This is the potentiality, the "what-it's-made-of." It's shapeless, indeterminate, and capable of taking on various forms. Think of a block of marble – it's matter with the potential to become many things.

- Form (morphe): This is the actuality, the "what-it-is." It's the organizing principle, the essence, the structure that makes a particular piece of matter into a specific kind of thing. It's the shape of the statue carved from the marble, the blueprint that actualizes the marble's potential.

An Illustrative Example: Consider a bronze statue of a horse.

- The Matter is the bronze itself – its metallic properties, its weight, its malleability.

- The Form is the specific shape of the horse, its equine essence, which distinguishes it from a bronze spear or a bronze pot.

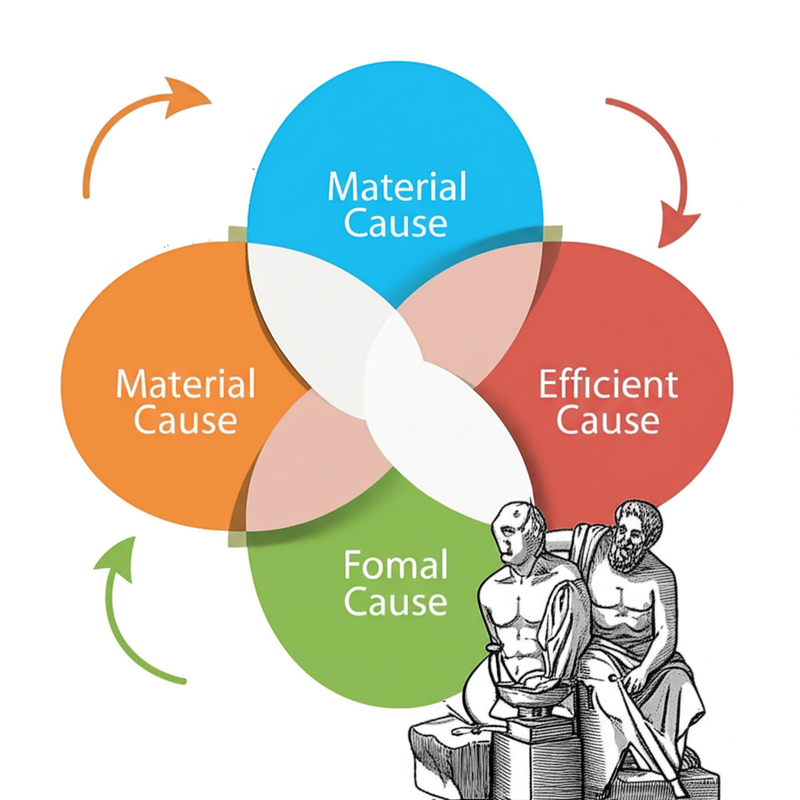

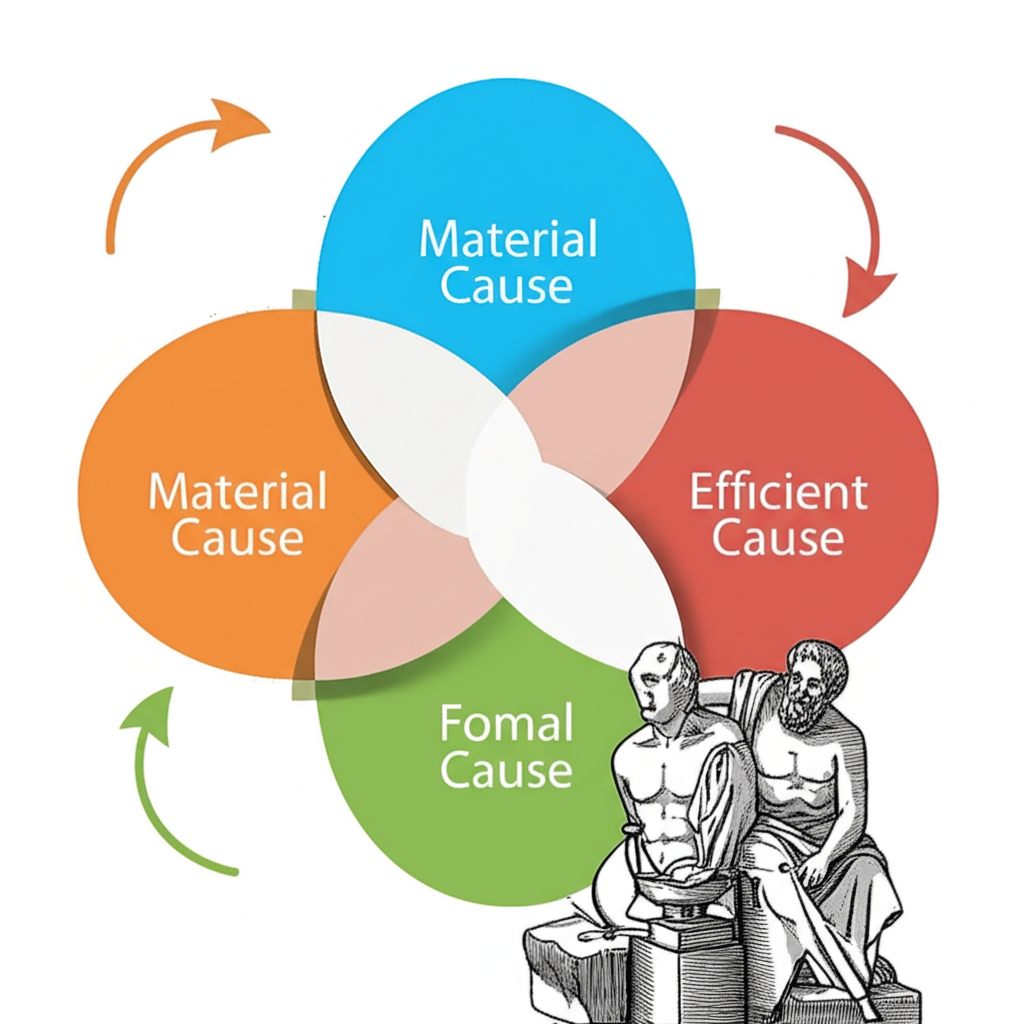

Aristotle explored these concepts extensively in his work, Physics, viewing the natural world as a dynamic interplay where matter strives to realize its potential through various forms. He further elaborated this through his famous Four Causes:

- Material Cause: What a thing is made of (e.g., the bronze of the statue).

- Formal Cause: The form or essence of a thing (e.g., the shape of the horse).

- Efficient Cause: The agent that brings a thing into being (e.g., the sculptor).

- Final Cause: The purpose or end for which a thing exists (e.g., to represent a horse).

The material and formal causes directly address the core of hylomorphism, showing how matter and form are inextricably linked in understanding the nature of physical objects.

, the intricate design in the sculptor's mind (formal cause), the sculptor himself in action (efficient cause), and a finished statue on a pedestal, representing its intended purpose or beauty (final cause), all set against a backdrop of ancient Greek architecture and a serene philosophical garden.)

, the intricate design in the sculptor's mind (formal cause), the sculptor himself in action (efficient cause), and a finished statue on a pedestal, representing its intended purpose or beauty (final cause), all set against a backdrop of ancient Greek architecture and a serene philosophical garden.)

Beyond the Ancients: Echoes in Modern Physics

While modern Physics has moved far beyond the philosophical musings of the ancients, the fundamental questions about the nature of reality persist. When contemporary Physics delves into quantum fields, subatomic particles, and the laws governing the universe, are we not, in a sense, still asking about Matter and Form?

- The matter of modern Physics might be seen in the fundamental particles – quarks, leptons, bosons – and the energy fields from which they arise.

- The form could be interpreted as the immutable laws of Physics, the symmetries, the organizing principles that dictate how these particles interact, combine, and manifest as observable structures – from atoms to galaxies. The very structure of DNA, for instance, is a complex form that dictates the matter of life.

The philosophical journey from identifying primal Elements to understanding the intricate relationship between Matter and Form has been a continuous thread in humanity's quest to comprehend the universe. It reminds us that even as science progresses, the profound questions first articulated by ancient philosophers continue to shape our understanding of existence itself.

YouTube Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Aristotle's Hylomorphism Explained"

-

📹 Related Video: SOCRATES ON: The Unexamined Life

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Presocratic Philosophers and the Elements"