The Physics of Change: Unraveling Reality's Dynamic Core

Summary: The Enduring Riddle of Flux

From the ceaseless flow of a river to the subtle shifts within our own understanding, change is the most pervasive and perplexing aspect of existence. This article delves into "The Physics of Change," exploring how both ancient philosophy—particularly as found in the Great Books of the Western World—and modern scientific inquiry grapple with the fundamental nature and mechanics of transformation. We will journey from the pre-Socratic insights into physis to Aristotle's sophisticated account of potentiality and actuality, revealing how the very fabric of reality is woven from dynamic processes, not static states. Understanding change is not merely an academic exercise; it is an essential step toward comprehending the world and our place within its perpetual motion.

I. Introduction: The Constant Unfolding of Being

"Everything flows and nothing abides; everything gives way and nothing stays fixed." These words, attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, capture a profound truth that has echoed through millennia of philosophical and scientific thought. The universe, in its grandest scale and its most minute details, is a symphony of change. Yet, how do things change? What are the underlying principles that govern this ceaseless flux? And what does "physics" – understood not just as modern science but as the ancient Greek physis, the study of nature itself – tell us about this fundamental process?

For centuries, thinkers have wrestled with the paradox of continuity within change. If everything is constantly transforming, how can anything retain its identity? This foundational question forms the bedrock of metaphysics and has, from its very inception, been inextricably linked to what we now distinguish as physics. The journey to understand change is, in essence, the journey to understand reality itself.

II. Ancient Insights: From Physis to Flux and Stasis

The earliest Greek philosophers, the pre-Socratics, were deeply concerned with physis, the inherent nature of things and the principles governing their generation, growth, and decay. Their inquiries laid the groundwork for what would eventually become both philosophy and natural science.

A. Heraclitus and the Doctrine of Perpetual Flow

Heraclitus, often called "the weeping philosopher" for his melancholic view of the world's impermanence, famously declared, "You cannot step into the same river twice." For him, change was the only constant, the fundamental principle of the cosmos. Reality was a dynamic tension of opposites, a perpetual flux where fire was the archetypal element, symbolizing continuous transformation. His philosophy insists that to truly grasp existence, one must embrace its inherent dynamism.

B. Parmenides and the Illusion of Change

In stark contrast, Parmenides of Elea argued that change was an illusion. For Parmenides, what truly is must be eternal, unchanging, and indivisible. If something is, it cannot become something else, for that would imply it was not before, and non-being cannot be. His rigorous logical deductions led him to conclude that the sensible world of change and multiplicity was a deception of the senses, and true reality was a unified, motionless plenum. This radical challenge forced subsequent philosophers, most notably Plato and Aristotle, to confront the problem of change head-on.

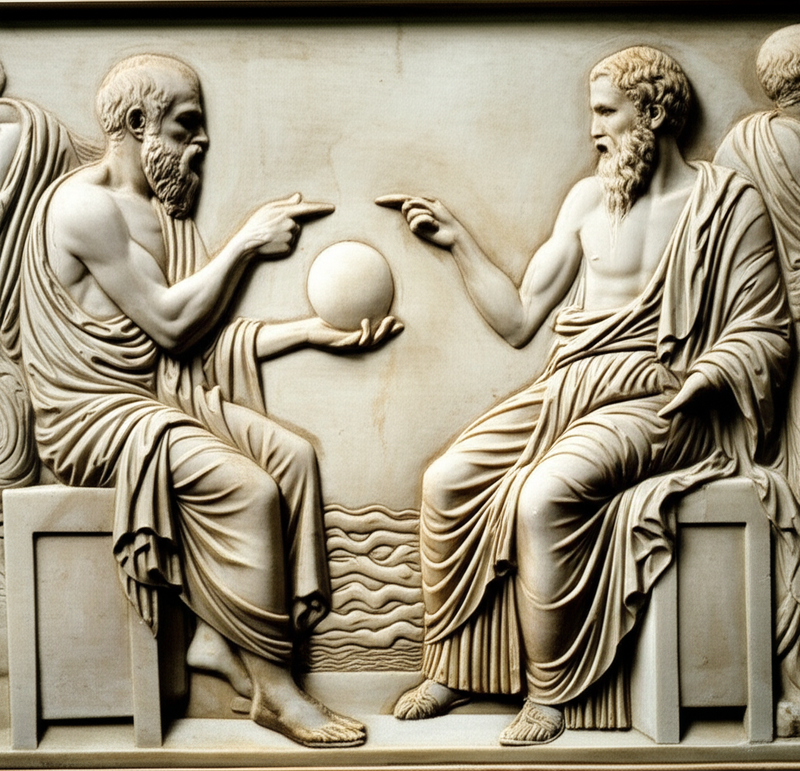

C. Aristotle's Synthesis: Potency and Act

It was Aristotle, whose works form a cornerstone of the Great Books of the Western World, who provided the most comprehensive and enduring framework for understanding change. In his treatise Physics, he directly addresses the problem posed by Parmenides and offers a nuanced solution. Aristotle posits that change is not the transition from being to non-being, but rather the actualization of a potentiality.

- Potentiality (Potency): The capacity for something to be or become something else. A seed has the potential to become a tree.

- Actuality (Act): The state of being realized or actualized. The tree is the actuality of the seed's potential.

Thus, change is understood as the movement from potentiality to actuality. A thing changes from what it is potentially to what it is actually. This brilliant conceptualization provides the fundamental mechanics of how things can transform without violating the logical principle that something cannot come from absolute nothingness.

III. The Mechanics of Being: Aristotle's Four Causes and Types of Change

Aristotle further elaborated on the mechanics of change through his doctrine of the Four Causes, which describe different explanatory factors for why a thing is what it is, and why it changes.

A. Aristotle's Four Causes

These causes are not merely "causes" in the modern sense of efficient causation, but rather explanatory principles:

- Material Cause: That out of which a thing comes to be and which persists (e.g., the bronze of a statue, the wood of a table).

- Formal Cause: The form or essence of a thing, its definition (e.g., the shape of the statue, the design of the table).

- Efficient Cause: The primary source of the change or rest (e.g., the sculptor of the statue, the carpenter of the table).

- Final Cause: The end, purpose, or goal for the sake of which a thing is done (e.g., the beauty or honor of the statue, the utility of the table).

These causes provide a holistic framework for understanding the nature of any given entity and its capacity for change. The material cause provides the potential, the formal cause defines the direction of actualization, the efficient cause initiates the process, and the final cause gives it purpose.

B. Categories of Change

Aristotle also identified distinct categories of change, demonstrating the varied ways in which things can transform:

| Type of Change | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Substantial Change | Generation and corruption; coming into being and passing away. | An acorn growing into an oak tree; a living creature dying. |

| Qualitative Change | Alteration; change in quality or accidental attribute. | A person becoming tan; a leaf changing color in autumn. |

| Quantitative Change | Increase or decrease; change in size or number. | A child growing taller; a population expanding or shrinking. |

| Local Change | Motion; change of place. | A ball rolling down a hill; a person walking from one room to another. |

This systematic approach to categorizing change highlights Aristotle's profound insight into the diverse mechanics of transformation that constitute the dynamic nature of reality.

IV. From Ancient Physis to Modern Physics: A Conceptual Shift

With the advent of the scientific revolution, the term "physics" gradually narrowed its scope. While ancient physis encompassed all of nature and its inherent principles of growth and change, modern physics became the study of matter, energy, and their interactions, often emphasizing quantifiable forces and mathematical laws. Thinkers like Isaac Newton, whose Principia Mathematica is another monumental work in the Great Books, provided a framework for understanding the mechanics of motion and change through universal laws of gravitation and classical mechanics.

This shift moved from a teleological understanding (final causes) to a primarily efficient-causal and mechanistic one. Yet, even in this more specialized domain, the fundamental questions about the nature of change persist. Quantum mechanics, for instance, introduces a probabilistic and observer-dependent aspect to change at the subatomic level, challenging classical deterministic views and re-igniting philosophical debates about causality and reality.

V. The Philosophical Resonance of Physical Laws

Even with the triumphs of modern physics, the philosophical underpinnings of change remain vital. Whether we speak of thermodynamic laws dictating the irreversible flow of entropy, or the relativistic distortions of space-time, change is always at the core. These physical laws don't just describe how things change; they implicitly inform our understanding of the very nature of time, causality, and existence.

The continuous dialogue between empirical observation and philosophical inquiry reminds us that "The Physics of Change" is not a closed chapter, but an ongoing exploration into the dynamic tapestry of reality. It challenges us to look beyond static appearances and recognize the potent, ever-unfolding processes that define all that is.

VI. Conclusion: The Unfolding Tapestry of Reality

From Heraclitus's flowing river to Aristotle's actualization of potential, and from Newton's laws of motion to the quantum uncertainties of the subatomic world, the concept of change has been central to humanity's quest to understand the universe. "The Physics of Change" is a testament to the enduring power of inquiry into the nature and mechanics of existence. It reminds us that reality is not a fixed monument, but a vibrant, living process, constantly in motion, inviting us to contemplate its profound and beautiful complexity.

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle on Change and Motion" or "Heraclitus vs Parmenides - The Problem of Change""