The Unseen Depths of "How Many?": Navigating the Philosophical Problem of Quantity

Summary:

The philosophical problem of quantity delves far beyond simple enumeration, probing the very nature of existence, perception, and definition. It asks whether quantity is an inherent property of reality, a construct of the mind, or a fundamental category through which we understand the world. From ancient Greek inquiries into the infinite divisibility of matter to modern debates on the nature of mathematical objects, philosophers have grappled with how "muchness" or "manyness" relates to being, challenging our most basic assumptions about the world we measure and describe.

Beyond Simple Counting: Unpacking the Philosophical Problem of Quantity

When we ask "how many?" or "how much?", the answer often seems straightforward. Three apples, five meters, a dozen eggs. Yet, for millennia, philosophers have found in this seemingly simple concept of quantity a profound wellspring of metaphysical inquiry, epistemological puzzles, and definitional challenges. Indeed, the very notion of quantity, far from being a mere descriptor, becomes a lens through which we scrutinize the fabric of reality itself.

This journey into the philosophical problem of quantity is not merely an academic exercise; it is an essential exploration for anyone seeking to understand the foundational assumptions underlying our sciences, our mathematics, and our everyday perception. Drawing from the rich tapestry of thought preserved in the Great Books of the Western World, we find this problem woven into the very earliest attempts to systematically comprehend existence.

Quantity as a Fundamental Category of Being

One of the earliest and most enduring philosophical engagements with quantity comes from Aristotle. In his Categories, he posits quantity as one of the ten fundamental ways in which things exist or can be described. For Aristotle, quantity is that by virtue of which a thing is said to be "so much" or "so many." It refers to discrete number (like a dozen men) or continuous magnitude (like a line or a body). This distinction is crucial:

- Discrete Quantity: Composed of indivisible units (e.g., numbers). One cannot meaningfully have "half" a man in the same sense one can have "half" a line.

- Continuous Quantity: Divisible into parts that share a common boundary (e.g., lines, surfaces, volumes, time).

Aristotle's framework immediately raises questions: Is quantity an intrinsic property of the object, or is it a relation we impose? If a forest contains 1,000 trees, is "1,000" an attribute of the forest itself, or of our act of counting? This leads directly into the heart of metaphysics.

The Metaphysics of Number: Real or Abstract?

Plato, a generation before Aristotle, presented a different, yet equally influential, perspective on quantity, particularly concerning numbers. For Plato, in the Republic and other dialogues, numbers were not merely abstractions derived from counting physical objects. Instead, they were perfect, eternal Forms existing independently of the sensible world. The "number Two" existed in a realm of pure ideas, and any pair of physical objects merely participated in this ideal Twoness.

This Platonic view presents a profound challenge to our definition of quantity:

| Perspective | Nature of Quantity | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Aristotelian | A property of sensible substances; inherent or accidental. | Quantity is discovered in the world. |

| Platonic | An independent, abstract Form; ideal and eternal. | Quantity informs the world; our world participates in ideal quantities. |

| Modern Nominalist | A name or concept we apply; a mental construct. | Quantity is a tool of the mind, not an inherent feature of reality itself. |

The debate continues: Do numbers exist in some objective sense, waiting to be discovered, or are they inventions of the human mind, tools for organizing our experience? This question lies at the very core of the philosophy of mathematics and its relationship to reality.

The Paradoxes of Division: Continuity and Discreteness

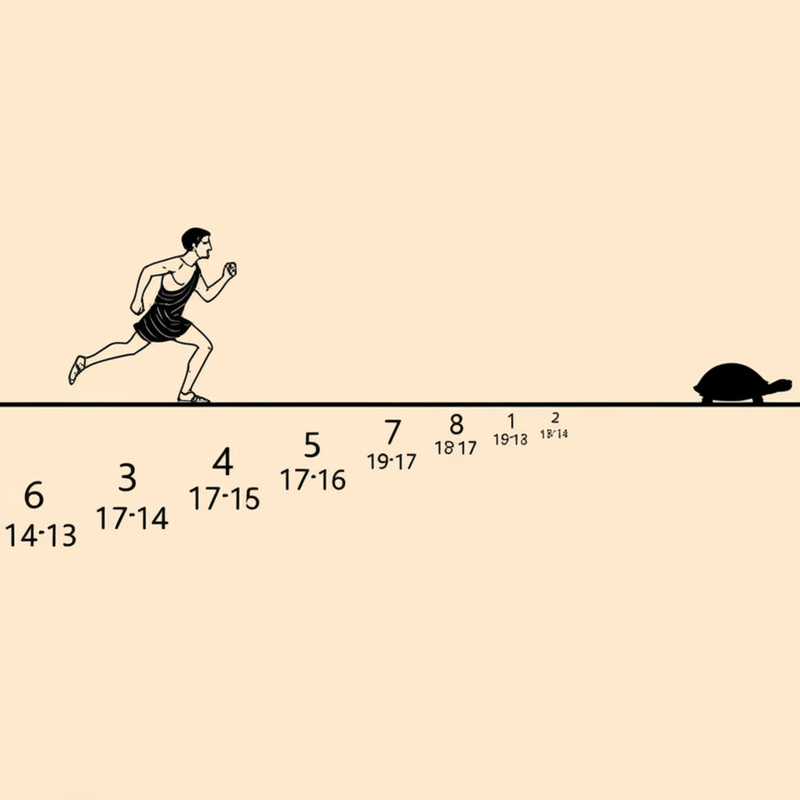

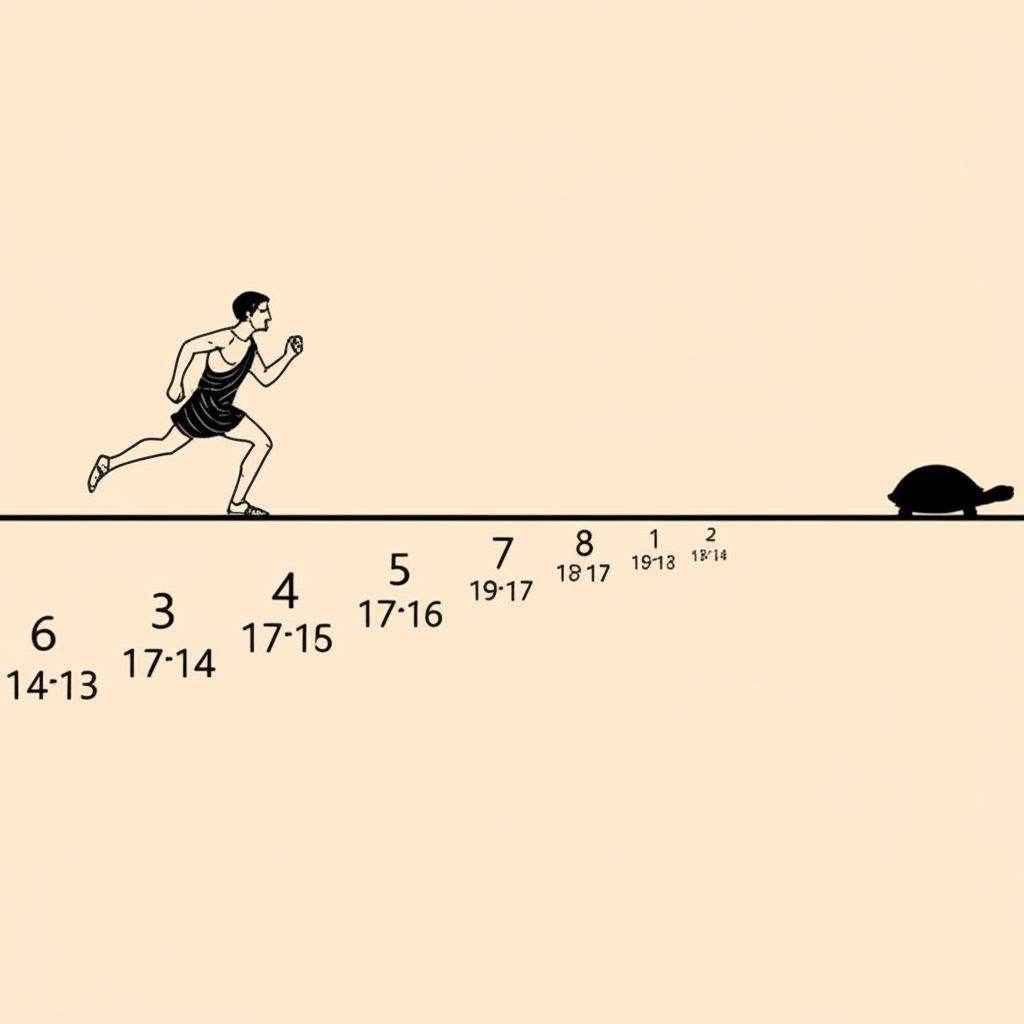

The problem of quantity is perhaps most famously illustrated by Zeno of Elea's paradoxes, discussed by Aristotle in his Physics. Zeno's arguments, such as Achilles and the Tortoise, or the Arrow, challenge our intuitive understanding of continuous quantity and infinite divisibility. If a line can be infinitely divided, how can motion ever begin or end? How can a finite distance be traversed if it contains an infinite number of points?

These paradoxes highlight the tension between:

- Intuition: We move; we traverse distances.

- Logic: Infinite divisibility seems to make motion impossible.

The resolution of these paradoxes has driven centuries of philosophical and mathematical thought, leading to the development of calculus and modern set theory. Yet, the underlying philosophical question remains: Is space and time truly infinitely divisible, or are there fundamental, indivisible units? Is continuity an inherent feature of reality, or an idealization?

Quantity's Relationship with Quality

Another crucial aspect of the philosophical problem of quantity involves its relationship with quality. While quantity tells us "how much" or "how many," quality tells us "what kind." A red apple (quality) and three apples (quantity) seem distinct. However, the lines can blur. Is "hotness" a quality, or a measurable quantity of kinetic energy? Is "beauty" purely qualitative, or can it be quantified through ratios and proportions?

Philosophers like John Locke, in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, distinguished between primary and secondary qualities:

- Primary Qualities: Inseparable from the object, regardless of our perception (e.g., solidity, extension, figure, motion, number). These are often considered quantifiable.

- Secondary Qualities: Powers in objects to produce sensations in us (e.g., colors, sounds, tastes). These are often considered qualitative.

This distinction, while influential, doesn't fully resolve the philosophical problem. If quantity is a primary quality, how do we justify its objective existence? If it's a secondary quality, then our measurements are merely subjective experiences.

The Enduring Quest for Definition

Ultimately, the philosophical problem of quantity is an enduring quest for a precise definition. What is quantity? Is it:

- A property of objects?

- A relationship between objects?

- A category of human thought (as Kant might suggest in his Critique of Pure Reason, where quantity is one of the categories of understanding through which we organize experience)?

- An abstract entity existing independently?

Each answer profoundly shapes our understanding of the world, from the foundations of physics to the nature of consciousness. The great thinkers, from Plato and Aristotle to Descartes, Locke, and Kant, have all wrestled with this fundamental concept, demonstrating its pervasive influence across the entire spectrum of philosophy. To ignore the philosophical problem of quantity is to overlook one of the most basic, yet challenging, aspects of our intellectual heritage.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Zeno's Paradoxes Explained Philosophy""

2. ## 📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Theory of Forms Numbers Philosophy""