The Grand Tapestry of Being: Unraveling the Philosophical Problem of One and Many

Have you ever looked at a forest and seen both individual trees and the unified entity of the forest itself? Or considered a symphony, recognizing both its distinct notes and its harmonious whole? This seemingly simple observation leads us to one of Philosophy's most profound and persistent challenges: the Philosophical Problem of One and Many. How do we reconcile the singular, unified nature of reality with its apparent multiplicity and diversity? This article delves into the historical and ongoing attempts to grapple with this fundamental question, exploring its deep roots in Metaphysics and the intricate nature of Relation that binds or separates the singular from the plural. From ancient Greek inquiries to modern analytical approaches, this enduring puzzle shapes our understanding of existence itself.

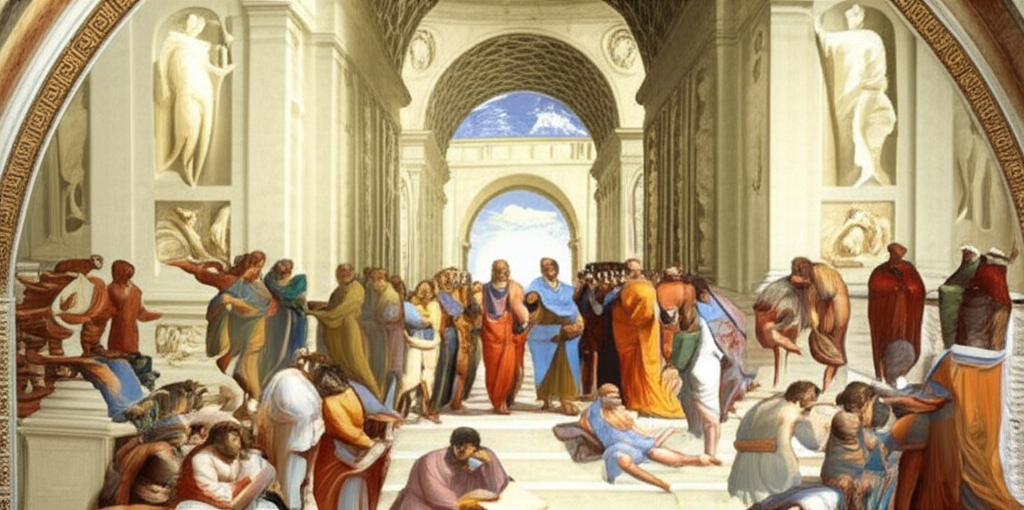

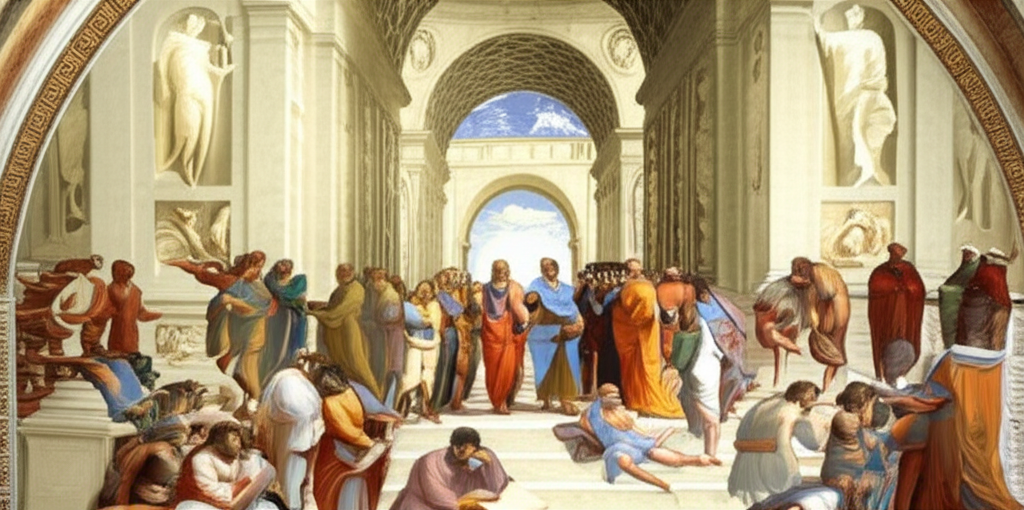

The Ancient Echoes: Parmenides, Heraclitus, and the Dawn of Metaphysics

The seeds of the Problem of One and Many were sown early in Western thought, long before the structured systems of Plato and Aristotle. Two pre-Socratic thinkers, whose fragments are treasured within the Great Books of the Western World, offer starkly contrasting views that beautifully encapsulate the tension.

Parmenides' Unchanging One: The Illusion of Multiplicity

For Parmenides of Elea, reality was fundamentally a single, indivisible, unchanging, and eternal One. Being simply is. Any apparent change, movement, or multiplicity that our senses perceive is nothing but illusion, a deception of the mind. To speak of "non-being" or "nothing" is illogical, for if it were, it would be something, a contradiction. Therefore, there can be no creation (coming into being from non-being) and no destruction (passing into non-being). The relation between this absolute One and the diverse world we experience is, for Parmenides, simply non-existent; the latter is merely a false appearance. This radical monism presented a powerful challenge to subsequent philosophical inquiry.

Heraclitus' Flux and the Many: The Reality of Constant Change

In stark opposition, Heraclitus of Ephesus championed the reality of constant change and becoming. His famous dictum, "You cannot step into the same river twice," captures the essence of his thought: everything flows, everything is in flux. For Heraclitus, the "Many" – the shifting, dynamic, and diverse phenomena of the world – were the true reality. Yet, even in this ceaseless change, Heraclitus posited an underlying unifying principle, the Logos, a rational order or law that governs the transformations. So, while emphasizing the Many, he still sought a One in the form of an ordered relation within the flux itself.

These two early Greek thinkers laid the foundational paradox, demanding that subsequent Philosophy confront whether reality is fundamentally unified and static, or diverse and dynamic.

Plato's Forms: Bridging the Divide with Ideal Universals

Plato, deeply influenced by both Parmenides' insistence on unchanging being and Heraclitus's observations of flux, sought to resolve the Problem of One and Many through his celebrated Theory of Forms.

The World of Forms: The One that Grounds the Many

For Plato, the transient, imperfect objects of our sensible world (the "Many") are merely reflections or copies of perfect, eternal, and unchanging archetypes residing in a higher, intelligible realm – the Forms (the "One"). For instance, while there are countless beautiful objects (beautiful flowers, beautiful songs, beautiful people), they are all beautiful because they participate in the singular, perfect Form of Beauty. This Form of Beauty is the ultimate One that grounds and explains the beauty in the Many particular instances.

The Challenge of Participation: The Intricate Relation

The real challenge for Plato, and indeed for all subsequent Metaphysics, lay in explaining the exact relation between these perfect, transcendent Forms and their imperfect, immanent copies. How does a particular beautiful object "participate" in the Form of Beauty? Is it a sharing? A resemblance? A mere imitation? This concept of "participation" became a central point of debate, highlighting the enduring difficulty in articulating the connection between the universal (the One) and the particular (the Many).

Aristotle's Substance: Grounding Reality in Concrete Particulars

Aristotle, Plato's most famous student, offered a different, more immanent solution to the Problem of One and Many. While acknowledging the need for stable principles, he found his "One" not in a separate realm, but within the "Many" particulars themselves.

Substance and Accident: Unity in Diversity

Aristotle's Metaphysics posits that reality is primarily composed of individual substances – concrete, particular things like a specific human being, a horse, or a tree. Each substance is a unified "One" composed of both form and matter, and it is capable of undergoing change while retaining its identity. These substances possess various accidental qualities (e.g., a human being can be tall, pale, or wise), which are the "Many" attributes inhering in a single "One" substance.

Categories and Universals: Immanent Relations

Aristotle developed a system of categories to classify the "Many" ways things can be predicated of a substance. For him, universals (like "humanity" or "redness") do not exist independently in a separate realm, as Plato believed. Instead, they exist in the particulars. The universal "humanity" is not a separate entity; it is the shared essence found in all individual humans. The relation between the universal (the One) and the particular (the Many) is thus one of immanence, where the universal is fully present within each particular instance.

Medieval Meditations: Universals, Particulars, and Divine Unity

The medieval period inherited the Problem of One and Many primarily through the Problem of Universals, grappling with the nature of general concepts (like "cat" or "justice") in relation to individual instances (a specific cat, a particular act of justice).

The Problem of Universals Revisited: Realism, Nominalism, Conceptualism

Philosophers debated whether universals:

- Exist independently of particular things and human minds (Platonic Realism, sometimes called "extreme realism" or "ante rem" – before the thing).

- Exist within particular things but not separately from them (Aristotelian Realism, "in re" – in the thing).

- Are merely names or labels we apply to groups of similar particulars, having no real existence outside the mind (Nominalism, "post rem" – after the thing).

- Exist as concepts within the human mind, formed by abstracting from particulars (Conceptualism).

These debates were crucial to medieval Metaphysics, influencing theology, logic, and epistemology.

God as the Ultimate One: A Theological Relation

For many medieval thinkers, the ultimate resolution to the Problem of One and Many lay in God. God was often conceived as the ultimate One, the perfectly simple and unified source from whom all the Many particular beings derived their existence. The relation between the Creator and creation provided a theological framework for understanding how immense diversity could arise from singular unity, offering a powerful answer within the dominant religious worldview.

Modern Perspectives: From Monads to Mereology

The Problem of One and Many continued to evolve through the modern era, taking on new forms with the rise of new scientific and philosophical paradigms.

Leibniz's Monads: Individual Unities Reflecting the Cosmos

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a prominent rationalist, proposed a universe composed of monads – simple, indivisible, mind-like substances. Each monad is a self-contained "One," a unique center of force and perception, yet each monad "mirrors" or reflects the entire universe (the "Many") from its own perspective. The harmony among these distinct monads is pre-established by God, offering a unique solution to the relation between individual unities and the cosmic whole.

Mereology and the Whole-Part Relation: A Formal Approach

In contemporary Philosophy, particularly in analytical Metaphysics and logic, the Problem of One and Many is often explored through mereology, the formal theory of parts and wholes. Mereology systematically investigates the relation between a whole and its parts, asking questions such as: When do parts constitute a whole? What kind of parts can a whole have? Are there ultimate, indivisible parts? This approach provides a rigorous framework for understanding how individual "ones" combine to form larger "ones," and how the "Many" can be understood as constituents of a unified whole.

The Enduring Metaphysical Puzzle: Why It Matters

The Philosophical Problem of One and Many is far more than an abstract intellectual exercise; it lies at the heart of our most fundamental understanding of reality. It underpins crucial questions in Metaphysics such as:

- Identity: What makes something one thing over time, despite its changing "many" properties?

- Change: How can a single entity undergo change without ceasing to be itself?

- Causality: How do individual causes (the Many) contribute to a single effect (the One), or vice versa?

- Consciousness: Is consciousness a unified "one," or merely an emergent property of many individual neural activities?

The diverse solutions offered by philosophers throughout history demonstrate the complexity and richness of this problem. Whether we emphasize the ultimate unity of being, the irreducible multiplicity of phenomena, or the intricate relations that bind them, our answer to the Problem of One and Many profoundly shapes our worldview and our place within the grand tapestry of existence.

Summary of Major Philosophical Approaches to One and Many

| Philosopher/School | Primary Emphasis on "One" | Primary Emphasis on "Many" | How They Relate (Relation) | Core Metaphysical Stance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parmenides | Unchanging, indivisible Being | Illusionary perception | Multiplicity is unreal | Radical Monism |

| Heraclitus | Underlying Logos (Order) | Constant flux, change | Logos orders the change | Philosophy of Becoming |

| Plato | Eternal, perfect Forms | Imperfect sensible particulars | Participation | Dualism (Forms & Matter) |

| Aristotle | Individual Substance | Accidents, categories | Immanent universals, inherence | Hylomorphism |

| Medieval Realism | Universal concepts | Individual instances | Universals exist independently or within particulars | Realism of universals |

| Nominalism | Individual instances | Universal concepts (names) | Universals are just labels | Focus on particulars |

| Leibniz | Simple Monads | Universe reflected in each monad | Pre-established harmony | Pluralistic Idealism |

| Mereology | Wholes | Parts | Formal part-whole relations | Formal Metaphysics |

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Why is the Problem of One and Many considered so fundamental?

It touches upon the very nature of existence, identity, and the structure of reality. Any attempt to describe the world, whether through science or philosophy, implicitly or explicitly addresses how individual things relate to larger wholes, and how diversity arises from unity. -

Is there a universally accepted solution to this problem?

No, there is no single, universally accepted solution. Different philosophical traditions and individual thinkers have offered diverse approaches, each with its strengths and weaknesses, reflecting the enduring complexity of the issue. -

How does this problem relate to modern science?

Modern science, particularly physics, biology, and cosmology, often grapples with analogous questions: How do elementary particles (the Many) form complex structures like atoms, molecules, and organisms (the One)? How does a single organism maintain its identity despite its cells constantly changing? These are empirical manifestations of the philosophical problem.

Suggested Further Exploration

- The Metaphysics of Identity: How do things remain the same over time?

- Mereology and Composition: The formal study of parts and wholes.

- Emergence: How complex properties arise from simpler components.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Parmenides vs Heraclitus explained""

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Theory of Forms simplified""