The Philosophical Weight of Our Toil: Unpacking the Meaning of Labor

Summary: Beyond mere economic activity or a means to an end, labor stands as a profound philosophical concept, deeply interwoven with the very fabric of human existence. From ancient contemplations on leisure and societal roles to modern critiques of alienation and the pursuit of self-realization, philosophy continually grapples with what labor means for Man, how it shapes our life, and even how it confronts our mortality in the face of death. This article explores these rich historical perspectives, revealing labor as a fundamental lens through which we understand ourselves and our place in the world.

Introduction: Beyond Mere Subsistence – The Human Condition and Our Work

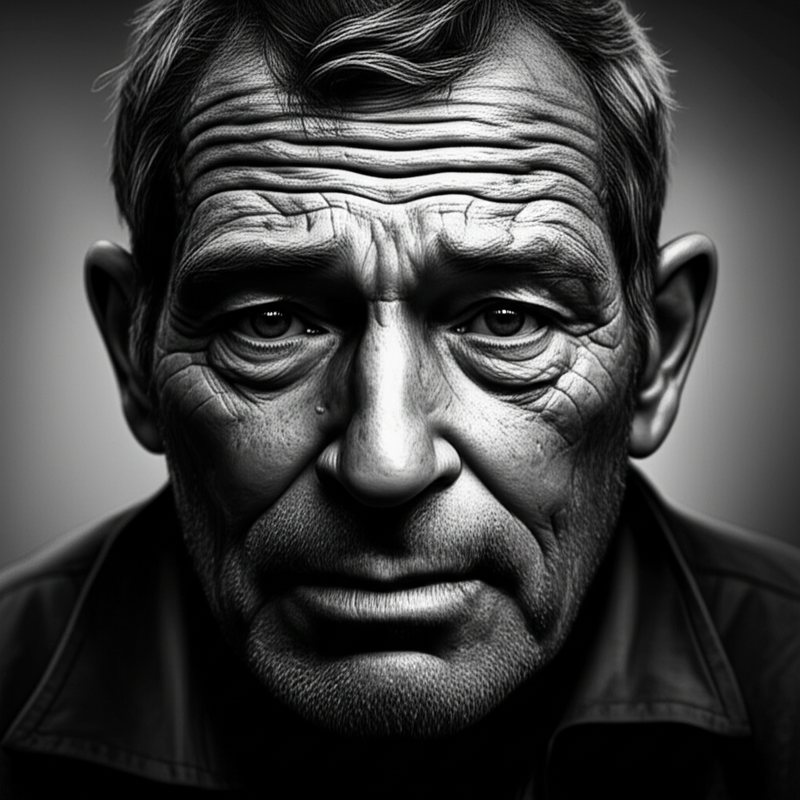

Every day, across cultures and epochs, Man engages in some form of labor. Whether tilling fields, crafting tools, writing code, or caring for others, work is an inescapable part of our shared experience. But what does it truly signify? Is it merely a necessary burden for survival, a curse, or a path to fulfillment? For millennia, philosophers have pondered these questions, elevating labor from a simple activity to a central pillar of ontological and ethical inquiry. Understanding the philosophical meaning of labor is crucial to grasping the essence of human identity, our relationship with nature, and the very structure of our societies.

I. Ancient Foundations: Labor, Leisure, and the Good Life

In the classical world, particularly among the ancient Greeks, the concept of labor was often viewed through a distinct social and philosophical lens. Figures like Plato and Aristotle, whose works form cornerstones of the Great Books of the Western World, articulated a vision where manual labor was largely seen as a necessary but lower pursuit, often relegated to slaves or artisans.

- Plato's Republic: In his ideal state, Plato envisioned a division of labor where different classes performed specific functions. While the philosopher-kings would rule and the guardians would protect, the producers (farmers, craftsmen) would engage in the physical labor necessary to sustain the polis. The life of contemplation, of philosophical inquiry, was considered the highest good, achievable only through the leisure provided by others' labor.

- Aristotle's Ethics and Politics: Aristotle echoed this sentiment, distinguishing between poiesis (making or producing, which has an end product outside the activity itself) and praxis (doing or acting, which is an end in itself, like contemplation or ethical action). He argued that true human flourishing (eudaimonia) required leisure, freeing individuals for intellectual and civic engagement. Labor, while essential for material life, was generally not considered part of the highest human activities. This perspective profoundly shaped Western thought, emphasizing the pursuit of wisdom over the toil of the hands.

II. The Medieval Lens: Toil as Penitence and Purpose

With the rise of Christianity, the philosophical understanding of labor underwent a significant transformation. Drawing from biblical narratives, particularly the Book of Genesis, labor acquired new dimensions – as both a consequence of the Fall and a path to spiritual redemption.

- Augustine and Aquinas: For thinkers like Saint Augustine and Saint Thomas Aquinas, labor was understood within a divine framework. "By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food" (Genesis 3:19) became a foundational text. Labor was seen as a form of penance, a necessary burden stemming from original sin. However, it was also imbued with purpose:

- Discipline and Virtue: Labor instilled discipline, humility, and deterred idleness, which was often seen as the devil's workshop.

- Service and Creation: Through labor, Man participated in God's ongoing creation, maintaining and shaping the world. It was a means to provide for one's family and community, an act of charity and service.

- Preparation for Afterlife: The hardships of labor in life were viewed as a spiritual exercise, preparing the soul for eternal life beyond death.

This era saw the dignification of labor, even manual labor, within a spiritual context, moving away from the purely pejorative view of the ancients.

III. The Modern Turn: Property, Self-Realization, and Alienation

The Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution brought forth radical new philosophical interpretations of labor, shifting focus from divine decree to human agency, economic systems, and the very nature of self.

A. Labor and Property: John Locke's Vision

John Locke, a pivotal figure in political philosophy, famously articulated the labor theory of property. In his Two Treatises of Government, Locke argued that an individual gains ownership over something in nature by mixing their labor with it.

- "Every man has a property in his own person: this nobody has any right to but himself. The labor of his body, and the work of his hands, we may say, are properly his."

- By applying one's effort to a common resource (e.g., picking an apple from a tree), one transforms it, making it their own. This act of labor is the foundation of private property and, by extension, economic and political rights. For Locke, labor is thus central to the individual's freedom and the establishment of a just society.

B. The Dialectic of Self: Hegel on Labor

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, in his Phenomenology of Spirit, presented a profound philosophical account of labor as a process of self-consciousness and self-realization. His famous "master-slave dialectic" illustrates this:

- The slave, through his labor, transforms nature, impressing his will upon the world. In doing so, he comes to see himself reflected in his creation. He overcomes the immediate, natural world and gains a sense of agency and self-awareness that the master, who merely consumes the fruits of the slave's labor, lacks.

- For Hegel, labor is not just about producing goods; it's about Man externalizing himself, shaping the world, and in turn, being shaped by his own efforts. It is a fundamental means through which consciousness develops and recognizes itself.

C. The Shadow of Alienation: Karl Marx's Critique

Building upon Hegel, Karl Marx offered a searing critique of labor under capitalism, particularly in Das Kapital. For Marx, labor is the very essence of human being, our "species-being" – the creative, conscious activity through which Man transforms nature and expresses himself. However, under capitalist conditions, this fundamental human activity becomes profoundly distorted:

- Alienation from the Product: The worker does not own the fruits of their labor; the product belongs to the capitalist.

- Alienation from the Process: The worker has no control over the conditions or methods of their work; it is dictated by others.

- Alienation from Species-Being: The creative, fulfilling aspect of labor is replaced by monotonous, dehumanizing toil.

- Alienation from Other Men: Competition and the social relations of production isolate workers from one another.

For Marx, alienated labor robs Man of his true life, turning him into a mere cog in a machine, leading to spiritual death and a life unfulfilled. His philosophy called for a revolution to reclaim labor as a source of human freedom and self-actualization.

IV. Labor, Meaning, and the Human Condition

In the 20th century, existentialist thinkers like Albert Camus further explored labor's relationship to meaning and absurdity. In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus uses the ancient Greek myth of a man condemned to eternally roll a boulder up a hill, only for it to fall back down, as a metaphor for the human condition. Sisyphus's labor is futile, repetitive, and seemingly meaningless. Yet, Camus suggests that Sisyphus can find meaning in the very act of rebellion against the absurd, in consciously embracing his fate.

This perspective highlights how labor, even in its most arduous or repetitive forms, can become a site for individual meaning-making, a defiance against the indifference of the universe, and a way to confront the finitude of life and the inevitability of death. We labor not just to survive, but to create, to connect, and to assert our presence in the world.

Key Philosophical Perspectives on Labor

| Philosopher/Era | Core Idea of Labor | Relation to Man, Life, Death |

|---|---|---|

| Ancient Greeks | Necessary but lower pursuit; antithetical to leisure and contemplation. | Sustains physical life, but true human flourishing (eudaimonia) is found in intellectual pursuits, freeing Man from the drudgery of toil. |

| Medieval | Penance for sin; means of discipline, service, and participation in divine creation. | Shapes Man's character, offers spiritual redemption, and prepares for eternal life beyond death. |

| John Locke | Source of property rights; mixing one's effort with nature. | Defines Man's natural rights and freedom, fundamental to establishing a just society and securing one's life and possessions. |

| G.W.F. Hegel | Process of self-consciousness and self-realization; dialectical engagement with nature. | Man transforms the world through labor and, in doing so, recognizes himself and develops his consciousness. It is a fundamental aspect of human development and life. |

| Karl Marx | Essence of human species-being; creative, conscious activity. | Under capitalism, labor becomes alienated, leading to the dehumanization of Man and a spiritual death of potential, preventing a truly fulfilling life. |

| Existentialism | A site for meaning-making in an absurd world; rebellion against futility. | Confronts Man with the meaninglessness of existence, but also offers the opportunity to create meaning through conscious engagement with one's tasks, affirming life in the face of death. |

Conclusion: The Enduring Question of Our Toil

From the ancient agora to the modern factory floor, from the theological scriptorium to the philosopher's study, labor has consistently challenged our understanding of Man. It is not merely an economic transaction but a profound existential act, shaping our identity, defining our place in society, and confronting us with the fundamental realities of life and death. The philosophical meaning of labor remains a vibrant and essential field of inquiry, urging us to continually reflect on the nature of our work, its impact on our humanity, and the kind of world we are collectively building through our toil.

YouTube:

- "Karl Marx Alienation of Labor Explained"

- "Hegel Master-Slave Dialectic Explained"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Philosophical Meaning of Labor philosophy"