The Weight and Wonder of Our Toil: A Philosophical Journey into Labor's Meaning

Summary: Labor, far from being mere economic activity, is a profound philosophical concept that shapes Man's identity, purpose, and relationship with Life and Death. This article explores how philosophers from antiquity to modernity have grappled with the essence of Labor, examining its role in human self-creation, societal structure, and the search for meaning in a finite existence. We delve into its historical interpretations, from ancient disdain to modern reverence and critique, revealing its enduring significance in the grand tapestry of human Philosophy.

The Inescapable Human Condition: Defining Labor Beyond the Grind

At the heart of human existence lies an activity so fundamental, yet so often taken for granted: labor. It is more than just earning a wage or performing a task; it is a primal engagement with the world, a transformative act that shapes both our environment and our very selves. From the earliest tool-making hominids to the complex algorithms of the digital age, Man has always been a creature that works. But what does this incessant toil truly mean? What philosophical truths does it reveal about our nature, our societies, and our place in the cosmos? This exploration delves into the rich history of Philosophy's engagement with Labor, drawing insights from the Great Books of the Western World to uncover its multifaceted significance.

From Burden to Blessing: Ancient and Medieval Perspectives on Toil

The meaning of Labor has shifted dramatically across historical epochs, reflecting evolving understandings of human dignity, societal structure, and spiritual purpose.

The Hellenic Divide: Contemplation vs. Craft

For many ancient Greek philosophers, Labor, particularly manual labor, was often viewed with a degree of disdain. Figures like Plato and Aristotle, whose ideas permeate the Great Books, emphasized the superiority of contemplation (theoria) and political action (praxis) over the mere production of goods (poiesis). For them, true freedom lay in leisure, which allowed for intellectual and civic engagement, while physical toil was seen as a necessary but ignoble activity, often relegated to slaves or the lower classes.

- Aristotle, in his Politics, posited that a truly virtuous citizen required freedom from the necessities of life to participate in the polis. Manual labor, by its very nature, was thought to hinder the development of intellectual and moral virtues.

- This perspective created a sharp division, where the man of leisure was the ideal, reflecting a society built on a specific economic and social hierarchy.

The Christian Ethos: Penance, Purpose, and Piety

With the advent of Christianity, the philosophical understanding of Labor underwent a profound transformation. While still acknowledging its arduous nature, Christian thinkers began to imbue Labor with spiritual significance.

- Augustine of Hippo, in works like City of God, interpreted Labor as a consequence of the Fall, a form of penance for original sin. Yet, it was also seen as a means of discipline, spiritual growth, and an act of obedience to God.

- Thomas Aquinas, building on Aristotelian thought but integrating Christian theology, further emphasized the dignity of Labor as a participation in God's creation. Honest work, he argued, contributed to the common good and was a path to virtue, even if certain forms of Labor were still considered more noble than others.

- This era saw the rise of monastic orders, where physical Labor (e.g., farming, copying manuscripts) was integrated with prayer and study, elevating its status as a path to piety and self-sufficiency.

The Modern Turn: Labor as Self-Creation and the Seeds of Alienation

The Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution ushered in radical new philosophies of Labor, shifting its focus from a burden or a spiritual exercise to a central pillar of human identity, property, and even the source of societal value.

Locke's Legacy: Property, Personhood, and the Fruits of Our Hands

John Locke, a foundational figure in modern political Philosophy, dramatically reoriented the understanding of Labor in his Two Treatises of Government.

- He famously argued that Labor is the source of property. When Man "mixes his labor" with nature, he imbues it with his own essence, thereby making it his own. This concept was revolutionary, grounding ownership not in divine right or inheritance, but in individual effort.

- For Locke, Labor was not merely a means to an end but a fundamental act of self-expression and self-ownership, essential for the development of individual liberty and personhood. It was through Labor that Man transformed the world and, in doing so, transformed himself.

Marx's Critique: The Paradox of Creation and Estrangement

Karl Marx, deeply influenced by the industrial conditions of his time, offered a powerful and critical analysis of Labor in works like Das Kapital and his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844.

- Marx agreed that Labor is a defining human characteristic, the very essence of Man's creative and productive being. Through Labor, humans externalize their ideas, transform nature, and realize their species-being.

- However, under capitalism, Marx argued that Labor becomes alienated. Instead of being a source of fulfillment, it becomes a means of survival, a commodity to be bought and sold. This alienation occurs in four key ways:

| Aspect of Alienation | Description | Impact on Man |

|---|---|---|

| From the Product | The worker does not own or control the fruits of their Labor. | The product becomes an alien power, dominating the worker rather than serving as an extension of their will. |

| From the Process | The worker has no control over how, when, or where they work; Labor becomes forced and external. | Labor ceases to be a free, self-directed activity and becomes a source of suffering and exhaustion. |

| From Species-Being | Man's essential creative and social nature is suppressed; Labor is reduced to a purely instrumental act. | Human potential is stunted; Man becomes less human, more animalistic in their struggle for survival. |

| From Other Men | Competition and class divisions create estrangement between individuals. | Social bonds are fractured; human relationships become transactional rather than communal. |

- Marx's Philosophy highlights the tragic paradox of modern Labor: the very activity that should define and fulfill Man becomes the source of his estrangement and dehumanization.

Labor, Legacy, and the Loom of Mortality: Connecting Life and Death

Perhaps the most profound philosophical dimension of Labor lies in its intimate connection to Life and Death. Our toil is not merely about sustenance; it is about leaving a mark, creating meaning in the face of our finite existence.

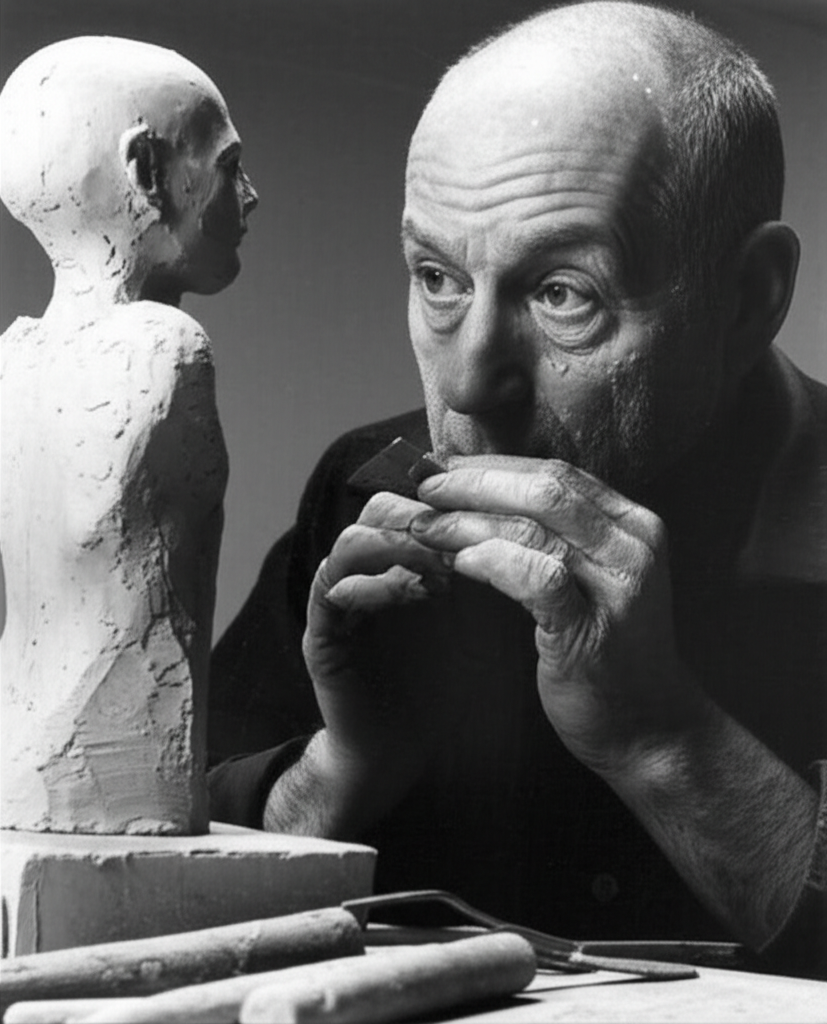

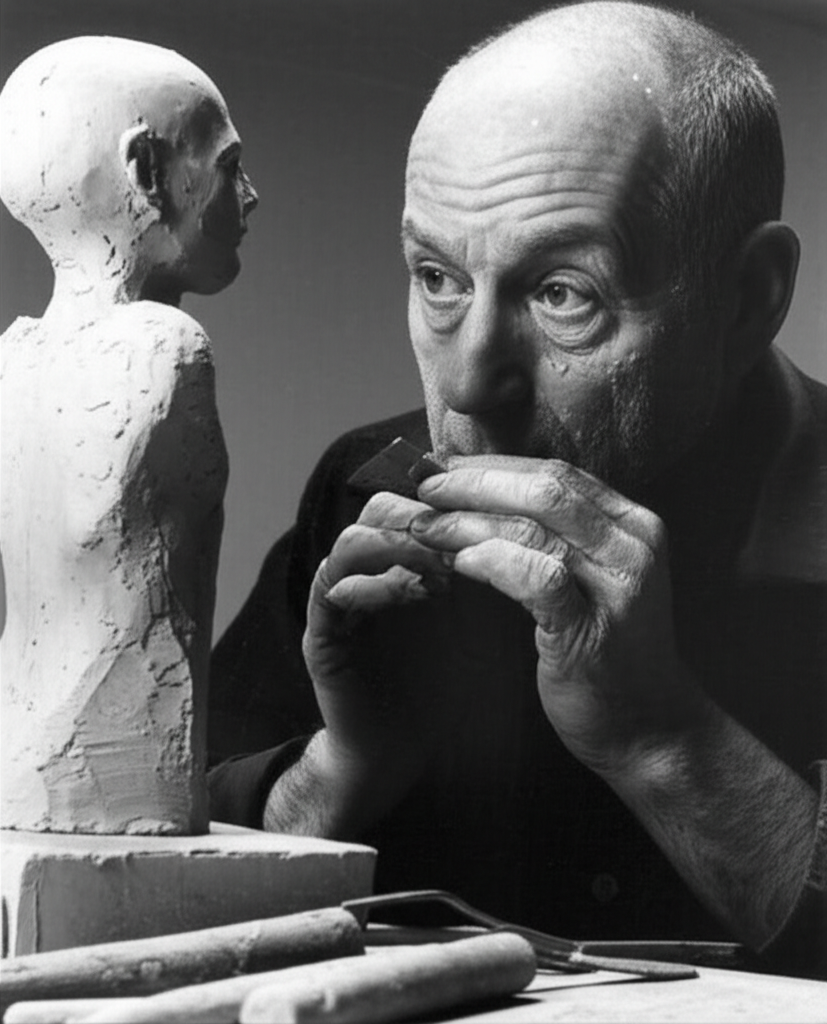

Building Worlds, Leaving Marks

Through Labor, we transform the world, constructing civilizations, creating art, advancing knowledge. These creations often outlive their creators, becoming a form of immortality, a legacy that transcends individual Life and Death. A farmer cultivates land for future harvests; an architect designs a building that will stand for centuries; a writer crafts narratives that resonate across generations. In each act, Man confronts his own mortality by creating something that endures. The collective Labor of humanity builds a shared heritage, a testament to our ongoing struggle and aspiration.

The Existential Weight of Our Work

The awareness of Life and Death imbues our Labor with an existential weight. Why do we strive, build, and create if all is ultimately perishable? This question drives much of existential Philosophy. Labor becomes a way of asserting our presence, of imbuing our brief existence with purpose and significance. The very act of working, of engaging with the world and shaping it, is an affirmation of life in the face of inevitable death. It is in our struggle, our creation, and our contribution that we find meaning, even if that meaning is ultimately self-authored. Our Labor is a dialogue with time, a defiant assertion against the void.

Conclusion: The Enduring Question of Our Hands and Hearts

From the ancient Greek's disdain to Marx's critique of alienation, and through every philosophical lens in between, Labor remains a central concept for understanding Man, society, and our place in the universe. It is simultaneously a burden and a blessing, a source of identity and alienation, a means of survival and a path to transcendence.

The philosophical meaning of Labor is not static; it evolves with our societies and our understanding of what it means to be human. As we navigate an increasingly automated and complex world, the questions posed by philosophers of old remain strikingly relevant: What kind of Labor truly fulfills us? How can we ensure that our work enriches rather than diminishes our lives? And what does our collective toil ultimately say about the ongoing human project, poised between the fleeting moment of life and the eternal silence of death? The answers, perhaps, lie not in a single definition, but in the continuous, thoughtful engagement with the work of our hands and the deep reflections of our hearts.

YouTube: "Marx's Theory of Alienation Explained"

YouTube: "The Philosophy of Work: Ancient vs. Modern Perspectives"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Philosophical Meaning of Labor philosophy"